Inside:

“Finally, the social history of America’s most destructive conflict might be fully underway.” So Susan-Mary Grant suggests, and the principal force will not be a “new” military history but what Grant calls “mortality studies.” … more

O Canada! A nation where even community, civility, and cultivation of a reading audience are problematic, at least where identity is concerned. Linda Morra explains why. … more

We are pleased to publish revised versions of the presentations on Ian McKay’s work-in-progress on “the Liberal Order” made by four distinguished historians as a round table, “Liberalism and Hegemony: Debating the Canadian Liberal Revolution,” during the 2009 annual meetings of the Canadian Historical Association on 25 May, 2009.

… Janet Ajzenstat

… Nancy Christie

… Jean-Marie Fecteau

… Martin Pâquet

Books

Ian McKay, Reasoning Otherwise: Leftists and the People’s Enlightenment in Canada 1890-1920 (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2008), 643 pages

Fall 2009

CANADIAN HISTORIANS, INCLUDING those who claim to be writing as leftists, are not known (at least lately) for their adventuresome ambitions. A light touch is deftly deployed to illuminate what are seen to be critically important discourses of difference. But the subjects of study have shifted discernibly. Why examine suffrage or class struggle, those old, tired topics? Have fun writing history, be progressive, and don’t belabour the politics too much. Considerations of class, gender, and race abound, but they often convey a sense of de-politicization.

Ian McKay breaks a lot of the contemporary moulds. Not only has he invested a great deal in writing the history of the Canadian left, he proposes to cover what he considers the entirety of the country’s oppositional project from 1890 to the present. An independent press, Between the Lines, has granted McKay four volumes to complete this audacious undertaking. A short introductory text, Rebels, Reds, Radicals: Rethinking Canada’s Left History was published in 2005, outlining McKay’s method and orientation, providing lengthy discussions of key terms, serving as an overview of what McKay calls five historically situated “socialist/left formations”: 1890-1919; 1917-1939; 1935-1970; 1965-1980; 1967-1990. A sixth formation, McKay suggests, is struggling to emerge out of the Canadian left’s participation in global justice movements and concern with the survival of our planetary ecosystem.

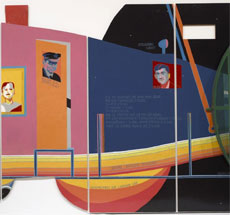

Hurdle for Art Lovers (1962)

Assemblage of wood, cast iron, plastic belt, oil-based paint, ink, silver knives, stainless steel knives with wooden and plastic handles, aluminum knitting needles, bamboo stick, silver spoons, steel screwdriver blade, and mastic knife, 100 x 158 x 26.4 cm. National Gallery of Canada. ŠThe Estate of Greg Curnoe

Reasoning Otherwise is the first substantive installment of this wide-ranging research agenda. McKay places his orientation to the history of the left at the interface of concerns scholarly and political, claiming that interpreting the world of Canadian socialism in new ways will help guide all those who want an end to injustice, poverty, environmental despoliation, inequality, exploitation, oppression, and bigotry today. Seeing the past of Canada’s left in all of its rich complexity will allow current oppositionists to think in ways that will help in the struggle to end what is wrong in our socio-economic system. A review of Reasoning Otherwise is necessarily an intellectual and a political engagement.

I

To the best of my knowledge, historians have not been questioning McKay’s method with the rigour that they should. There is a danger that activists, engaged in the hurly-burly of changing the world, will read McKay and assume (as others have, according to the promotional blurbs) that this significantly suggestive foray is somehow definitive or free of a variety of foibles. Let me outline briefly McKay’s conceptual premises, suggesting why I find them, at times, problematic. Then it will be possible to explore the strengths and weaknesses of McKay’s presentation of what he considers Canada’s “first socialist left.”

In both Rebels, Reds, Radicals (RRR) and Reasoning Otherwise (RO) McKay suggests that “left-wing effectiveness in Canada comes down in large part to how skilfully and subtly liberal order is pushed to its definitional limits.” (RRR, 84) McKay understands liberal order as a pervasive project, stretching in Canada from the 1840s to the 1940s (although why, given his conceptualization, this long Liberal Revolution should not extend to the present is a legitimate question) in which liberty, equality, and private property are sanctified as the foundations of a civil society that valorizes individualism. McKay’s arguments about liberal order are often vague, overly generalized, and, of course, impose on past leftists a terminology they themselves did not use. (Radicals and revolutionaries of the pre-1920 years would indeed have set their critical eyes on what they designated capitalism, which they might have referred to, in specific contexts, as plutocracy, wage slavery, or, loosely in the immediate post-World War I era, Kaiserism. They never spoke of an enemy that they named ‘liberal order.’)

As an elastic category, liberal order can contain almost anything associated with what has traditionally been understood about modern developing societies, premised as they are on property relations of inequality and bourgeois individualism. In Canada, the dissident politics of advocates of responsible government in the 1840s, such as Robert Baldwin, and even the bourgeois insurrectionism of his fiery counterpart, the rebel leader of the 1830s, William Lyon Mackenzie, can be considered to be building blocks of ‘liberal order.’ So, too, are the infinitely adaptable policies of Mackenzie’s grandson, Willie ‘Industry and Humanity’ King, the British Commonwealth’s longest serving prime minister. Even the divergent but related federalisms of a Conservative traditionalist such as John Diefenbaker or that paragon of Liberal modernity, Pierre Trudeau, can be placed, with nuance, inside the expansive ‘container’ of liberal order. National policies of tariff protection in the 1880s and free trade initiatives in the 1980s can just as easily fit into the paradigm.

The danger in deploying liberal order in this way, as a seemingly trans-historical analytic framework, is that it actually sidesteps the need to confront and elucidate capitalism’s changing historical structures and their many and varied (in specific nation-state settings) consequences, policies, and agenda-setting priorities. Contrary to McKay’s assertions, moreover, it may well be impossible to discern anything distinctly Canadian about the notion of liberal order. Certainly the United States seems to follow liberal order imperatives, although McKay does little of the kind of comparative historical assessment that would be necessary to sustain an effective argument about how Canada is peculiarly situated in what is being claimed is a new conceptual framework. The most serious problem with the liberal order perspective, then, is that it allows mainstream historians to avoid confronting just how critically important it is to name the frontline enemy: capitalism as systematic exploitation and endlessly proliferating oppression.

The acceptance of McKay’s liberal order framework in so many historical circles speaks to a dual tendency in contemporary academic life: 1) the thirst for an overarching framework to replace the ‘world we have lost’ with social history’s fragmenting stress on the particular and the specific and the extent to which theoretical frameworks such as Harold Adams Innis’s political economy or its Creightonesque adaptation are now clearly dated and inadequate; 2) the attractiveness of skirting capitalism by attending less to the shifting material foundations of capital’s dominance and more to its ongoing apparatus of accommodation. McKay is not necessarily captive of such tendencies himself, but his framing of the liberal order paradigm is surely cognizant of contemporary academic trends.

This is not unrelated to McKay’s adaptation of the Gramscian concept of hegemony, which, I would suggest, understates Gramsci’s clearly multi-sided articulation of the complexities of class rule, laid out in the admittedly opaque (written as it was under the constraints of incarceration and the watchful eye of jailguard censors) and posthumously published Selections from the Prison Notebooks. McKay’s elastic understanding of Gramsci’s hegemony conflates what Gramsci differentiated as a “separation of powers” associated with organizing social hegemony within civil society and enforcing discipline through various vehicles of state domination, a dual process that Gramsci insisted gives rise to “a particular division of labour and therefore to a whole hierarchy of qualifications.” All of this was also, most importantly, distinct from the non-superstructural realm of material, productive life, where disciplines of other kinds were operative.

McKay has a more seamless, unitary understanding. He notes that “a group, usually closely tied to a class,” that “achieves power” makes “historical choices” about how it ensures its legitimation, “for instance, constructing a liberal order.” Such a vague formulation (note how its very language adopts an almost Gramscian evasion, albeit in a context decidedly different than that in which the imprisoned Italian Marxist wrote) manages to miss addressing capitalism at the same time that it collapses the social differentiations, divisions of labour, and hierarchies of qualification that Gramsci rightly flagged as critically important. According to McKay, “The theory of hegemony refers not just to ideas, but also to the material forms that generate them and the social agents they attract. … In Canada, since the 1840s, liberal hegemony has worked at the deepest levels, organizing the very ways in which the ‘individual,’ ‘state,’ and ‘economy,’ for example, are framed, analyzed, and changed.” (RO, 5)

The problem with this elasticity is that it may well stretch too much. It fails to acknowledge that capitalist power and authority has some non-incorporative wellsprings of its own, of significant material import, existing outside the Gramscian boundaries of the hegemonic. The domination of the state is both a social and cultural construction, and something other than this as well, as is the governance of capital. Hegemony and the arm twisting that it invariably entails needs to be understood as an undertaking that is always capable of being supplemented (or supplanted) by quite tangible and often devastating recourse to other disciplining agents: the empty stomach; the lethargy and enervation of the working day; the prod of the gendarme’s bayonet; the searing blindness of teargas; the jail cell; the hangman’s noose.

If we were to step outside of McKay’s Gramscian reading of hegemony, exploring, for instance, how revolutionary Social Democrats in the first decades of the 20th century employed the term hegemony as shorthand for the never-ending class struggle, our understandings take on subtle, but important, shades of difference. Bolsheviks such as Lenin and Zinoviev spoke of hegemony in ways that turned decisively on the need to develop socialist consciousness within the institutions of the workers’ movement so that Revolution could triumph. The issue is complicated because it balances on complexities, complicated historically by the very different environments in which revolutionaries struggling for and attaining power wrote about programmatic social transformation, as opposed to Gramsci’s attempts to theorize the class struggle within the confines of defeat and incarceration.

There is no denying that the meaning of hegemony among revolutionaries who lived within the accomplishments of 1917 varied from those Western Marxists whose formative appreciations of the term were conceptualized in moments of deeper pessimism. If the optimism of revolutionary will, on one side, produced a more precise and politically focused articulation of hegemony, on the other a pessimism of the intellect necessitated broader, and often more cultural, formulations. Political clarity and focus on revolutionary achievement gave way to looser, more vague, discussions, in which the struggle for power, in political and material terms, was increasingly likely to take on culturalist trappings used to explain the staying power of the ancien régime. While the intellectual benefits of the latter may seem obvious to us today, living as we do in the skin of a non-revolutionary situation, it is not necessarily the case that this is the best way to understand a past where the burden of defeat did not press on generations of dissidents with the same oppressive weight that has disfigured the project of socialist possibility in our times. Nor should we understate the extent to which this evolution, however seemingly sophisticated and nuanced in its analytic advancements, fit well within Gramsci’s particular, and decidedly limiting, political and material circumstances.

If we move from McKay’s use of terms like liberal order and hegemony to his method of what he calls “reconnaissance,” confirmation of his elasticity also surfaces. Indeed, it is on the assertion of reconnaissance as an entirely new approach to understanding the history of socialist/left formations that McKay stakes the intellectual innovation and political value of his project of recovering Canada’s lost lefts. It is also where discerning readers – as thinkers and doers on the left – will want to look and think carefully at what is being said.

II

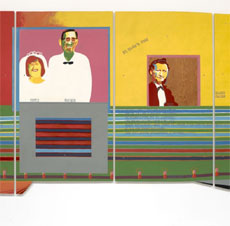

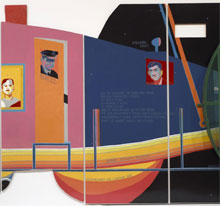

Homage to the R-34 (1967-68) detail.

Enamel paint on plywood and steel, 2.95 x 31.54 x .025 m overall, National Gallery of Canada (MGC+39705.1-26K) ŠThe Estate of Greg Curnoe

This notion of reconnaissance, as outlined in RRR and RO, suggests a number of principles of investigation. First, reconnaissance, McKay insists, is not synthesis, which he asserts is a comprehensive, final, statement. (RO, 1) Yet I can think of few scholars who, when writing synthetic overviews of a subject, approach the field in this way, or even think themselves capable of providing the ultimate, definitive text. Syntheses, rather, are more often written to summarize knowledge up to a given point, to structure thought in ways that allow coherence to emerge out of the seeming chaos of proliferating commentary. McKay presents synthesis as little more than politicized caricature. “A radical-democratic reconnaissance,” he writes, “contrasts with a mainstream academic synthesis. My image of the latter is that of a white coated scientist in a laboratory, his individual genius demonstrated by a blackboard covered with equations. He is coolly holding a beaker – containing the ‘synthesis’ – in his hand.” Reconnaissance, according to McKay, is risk-taking, venturesome, and conveys a sense of “heterogeneity and surprises of a little-explored landscape.” It takes political chances that academics, “who like to hang out in gangs and arm themselves with sharply worded footnotes,” are neither willing nor able to undertake. (RRR, 94-95) Reconnaissance is good and left-leaning and virtuous; synthesis is scholastic, short-sighted, school-bookish. But all of this is little more than assertion. Some who have written syntheses have done so in ways that are not far removed from McKay’s claims for reconnaissance. They are just as aware of the difficult politics of choice that determines what is left in and what is excluded, what is accented and what is understated. There is little if anything in any of McKay’s writing that concretely discusses any syntheses that are flawed by the characteristics he attributes to a genre. Reconnaissance, then, is a label of McKay’s making. It is posed polemically against a rather mechanical representation of a way of writing that strives to attain a certain pedagogical purpose.

Second, McKay claims that reconnaissance is the antonym of polemic. His entire approach is self-designated as “post-polemical reconnaissance.” McKay does indeed have some useful things to say about the necessity of recognizing the provisional nature of knowledge and how all historical writing has to be both present-minded (understanding the urgency of grasping the great importance of leftists actually knowing their past) AND anti-presentist (refusing to fall into the trap of reconstructing that past on the basis of present values). (RO, 3) And yet for all this resistance to polemic, McKay’s approach is, arguably, about as polemical as historical writing can be.

The deception at the core of McKay’s sleight of hand around the issue of polemic operates, initially, at the level of general dismissal. Thus, both RRR and RO are adamant that past writing on the Canadian left is impaled on the twin horns of sentimentality and sectarianism, producing what McKay labels “the scorecard approach.” Histories guilty of this are apparently “pervasive.” They rest on “hubristic arrogance,” their authors believing they can “infallibly bestow or deduct points.” (RRR, 81-82) McKay’s reconnaissance method aims to itself reason otherwise against the “morality tales and onwards and upwards master narratives.” (RO, 3) “Thousands of books and articles have been published, and theses written, about the Canadian left,” claims McKay – in what I think is surely overstatement unless, of course, the definition of what constitutes writing on the left is exceedingly elastic. Nonetheless, according to McKay, this rich bibliography needs an analytic overhaul, one that transcends the all-too-common political agenda simmering in ideological flames fanned by partisan authors serving up a “potent brew of sectarianism and sentimentality.” McKay writes that sectarians have envisioned the history of the left as though “our tradition has the goods, and every other approach to the left is mired in error and illusion.” Sentimentalists declare “our heroes were never complicated, cowardly, or inconsistent.” The historiography of the Communist Party is little more than an alignment of opponents, arguing positions out “in polemical texts and poisonous footnotes.” (RRR, 22, 113)

“Sectarianism and sentimentalism, and point-scoring histories, have become tiresome and, much worse, politically counterproductive,” argues McKay in opening Reasoning Otherwise. (11) This generalized attack on sentimentality, sectarianism, and the scorecards they produce is socially constructed as not being polemical. Really! The only way this fiction can be maintained is that McKay, in these generalized put-downs, does not cite any actual texts. In most cases he brings no evidence to bear on his assertions save the weight of his own confident proclamations. There are of course times in RO that McKay does differentiate himself from named authors as well as from socialists in the past—and when this happens it, too, undermines the claim that this book is somehow post-polemical. But his overall orientation rests on a blanket rejection.

Once this is understood, it is relatively clear that McKay, too, writes in scorecard ways. His footnotes bestow and deduct points on and from the literature with a surprising (given his stated aversion to this) ‘infallibility’. Specific writings are path-breaking and superior, some “almost magisterial”; others are ignored or mentioned only in a kind of obligatory passing; still more singled out for criticism.

The third feature of McKay’s method of reconnaissance is that he concentrates less on identifiable and often organizational aspects of socialism’s early Canadian history than has been the norm in past writing. Instead, he strives to capture what distinguishes a particular ‘left formation’ and how it gives way to a different analytic framework among leftists: what McKay designates a point of supersedure. Parties, mobilizations, manifestoes, writings, and struggles figure in his history, but less so than what McKay sees as constellations of thought – reasoning otherwise – that crossed lines of alignment within the left but that brought a formation together. What is worth flagging conceptually is the extent that this approach, which has the value of bringing together conflicted histories within the left also has the downside of understating important demarcations. It reproduces the problems of elasticity evident in McKay’s understanding of liberal order and hegemony. For McKay, the critical differentiation in the period covered by RO is what distinguished early socialists in Canada from the mainstream liberal order. “Even when leftists were arguing with each other, they were at least sharing enough of a common language of leftism that their arguments were mutually intelligible,” explains McKay. “Even when they were not connected by shared institutions, we can, judiciously, bring them together within the analysis of a formation if it can be shown that they were connected through a shared language of politics.” (RO, 7) That “language of politics” is of course constructed out of writings, mobilizations, manifestoes, and party activities, but they themselves are, within McKay’s reconnaissance, less important than what the historian doing this reconnaissance determines is relevant as ‘left formation’.

Socialism thus ‘happens’ for McKay largely as an act of subjective choice, in which “people willingly throw themselves into the revolutionary dialectic of the historical process.” It is not so much a creation, an actual alternative to capitalism that needs to be fought for, achieved, and then continuously built and sustained – an objective realization – as it is a process of thinking and living differently. This individual embrace of reasoning otherwise is, for McKay, as important as the establishment of parties of socialist opposition because such parties, their programs, and their mobilizations are but vehicles through which human attempts “to understand and escape the contradictions of bourgeois order” are consolidated. This is the truly profound counter-hegemonic act, and for McKay it outstrips the significance of parties and leaders, although, to be sure, in RO he spills considerable ink outlining the development and ideas of a range of individuals who were in fact appreciated as leading actors in the Canadian left. In this elevation of subjective human alignment, McKay situates his own method and sensibilities within what he designates the individuated liberal order. Thinking other than what is required within liberal order is itself presented as the making of system-changing socialist possibility. Translating this thought into the action that concretely changes the world we live in concerns McKay less. (RRR, 142-143) He thus understandably steps into the past to build a kind of ‘socialist formation’ out of fragments, individuals, experiences, and thought that were never as unified as McKay is making them.

Such a perspective, as McKay acknowledges, does indeed shift how one understands socialism’s advance and the transformation of socioeconomic life. It reframes debates over reform versus revolution that McKay obviously thinks are tired and counterproductive, but that ring in many ears to this very day. “It is quite possible,” he writes, “to regard oneself as a complete revolutionary, identifying with a ‘homeland of the revolution’, reading revolutionary theorists all day long and belonging to a revolutionary party and not, ultimately, manage to say or build anything of lasting revolutionary – that is, system-challenging – significance. Conversely, it is equally possible to regard oneself as a mild-mannered, middle-of-the-road pragmatic reformist, without any interest in blood and thunder – and to say words and do things that lead people to act in system-challenging ways.” (RRR, 79) Words such as these, framed as a binary opposition (with one side implicitly denigrated and subject to a subtle sarcasm, the other validated in its modesty and accomplishment), suggest that the architect of reconnaissance as a strategic mode of understanding might well himself be succumbing to certain prejudices.

III

Reasoning Otherwise, which begins with rather self-referential assertions of the superiority of this theoretical/methodological framework, takes us out of the realm of conceptual and methodological claims – repeated, mantra-like, by McKay in a variety of forums – and into the sphere of a demonstration of what can be delivered. The result is a mixed accomplishment, in which the valuable predominates, but the questionable is ubiquitous.

McKay understands the first formation of Canadian socialism, which he suggests emerged in the 1890s and lasted through the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919, as defined by its broad adherence to “the revolutionary science of evolution.” Across the length and breadth of a country always divided by regionally differentiated political economies, where nation was a hybrid formation situated at the interface of local and international developments and influences, McKay insists that what united the socialist formation of this period was the thought and language of what he calls a Karl Marx-Herbert Spencer continuum. That Canadian socialism would owe a great deal to Marx comes as no surprise, but it is McKay’s accent on the importance of Herbert Spencer that will perhaps raise some eyebrows. It should not: Spencer, as one of the 19th-century English-speaking world’s most celebrated and widely published thinkers, was seldom much farther than an arm’s length from any reading individual. You had to have a longer reach, and greater determination, to grab hold of Marx as an English-speaker/reader in this same historical period.

On the one hand, McKay’s insistence that Spencer’s influence helped to shape early Canadian socialism is insightful, although not terribly original; the point has been made in a number of United States treatments of the intellectual history of late 19th-century socialism/radicalism. Society, in Spencerian terms, was able to be perceived as an organism that evolved and changed, not unlike the natural world. Leftists could loosely adapt Spencerian thought to suggest that to oppose revolution was to stand against that break into new possibilities that evolution itself demonstrated scientifically. Publishing houses of the left, like Chicago’s Charles H. Kerr, produced a proliferation of texts that addressed, in the title of one Arthur M. Lewis book, Evolution: Social and Organic. It is difficult to imagine today much socialist writing carrying titles like The Law of Biogenisis or Germs of Mind in Plants, but these were publications many workers and socialists read and learned from in the pre-World War I years. In the autodidactic culture of often self-taught socialists, science and the Darwinian method and its insights were powerful weapons. They were used by radicals to take direct aim at the superstition and cant of various orthodoxies that were widely regarded on the left as props of antiquated traditionalism and all that it sustained.

On the other hand, developing this insight and having grasped its importance, McKay too aggressively and indiscriminately structures the entire left formation into an all-too-often uncritical assimilation of Spencer. Too little attention is directed in McKay’s construction of a socialist ‘Spenceria’ at the extent to which socialist writers argued that Marx completed Darwin and Spencer. Moreover, McKay tends to collapse Darwin and evolutionary science into Spencer, something that many leftists of the 1890-1920 years did not do. Indeed, Spencer would not let them. Late in his life he bent his pen repeatedly against those left Spencerians like Enrico Ferri, whose Kerr-published Socialism and Modern Science (1900)was something of a brief for McKay’s claims about Spencer’s influence. Spencer expressed his hostility towards Ferri, whom he denounced as having “the audacity” to “make use of his name to defend socialism.”

Like bourgeois society and its thought, which he in many ways encapsulated, Spencer was two-sided: his thinking was born revolutionary but over time consolidated in its conservatism. By the 1880s, when most of the revolutionaries of McKay’s first socialist formation were either about to be born or had come of age politically, Spencer was discredited on the left, his writing distorted by fears of ‘the coming slavery’ of collectivist societies that had abandoned the value that needed to be placed upon individualism as the safeguard of all human progress.

More balanced than McKay, who sees behind every possible socialist reference to evolution and progress a “Spencerian” trace, is the judgment of William D. Bliss’s 1897 Encyclopedia of Social Reform. Bliss insisted that Spencer’s repudiation of his early radicalism had “hurt his influence among the masses” and that few could now not recognize that Spencer was a “steadfast foe of all steps tending toward socialism.” The highly influential socialist orator and author, Arthur Lewis, was even more blunt in 1907 when he declared unequivocally, “The greatest name ever thrown into the scales for Individualism against Socialism is that of Herbert Spencer.”

McKay knows this, but his reconnaissance understates it. Spencerian influences are seen everywhere by McKay, precisely because his vision of their presence is so loose and elastic that they can be conjured up where, in fact, they may not exist. And once a specific left formation has been defined in good part in relation to a figure like Spencer, it is difficult to acknowledge that many in that same formation rejected Spencer as outdated and saw him as an intellectual enemy, a political prop shoring up capitalism’s project of acquisitive individualism. This problem runs through RO, but two examples from the beginning and end of McKay’s 1890-1920 period illustrate how the reconnaissance of Spencerian influence can derail in misreadings of the past.

A central early figure in Canadian socialism was T. Phillips Thompson, a radical journalist, Knights of Labor writer and thinker, and eventual founding member of the Canadian Socialist League, established in 1901. McKay presents Thompson as a sentimental favourite in certain quarters (here McKay actually polemicizes against other writers, including Thompson’s grandson, the popular writer Pierre Berton, in ways that I found strained, ineffective, and unnecessarily mocking). This “Grand Old Man of Canadian Socialism” is claimed by McKay to have graduated, by the 1880s, from “[Henry] George to [Edward] Bellamy and Spencer.” This in fact gets the trajectory wrong. It would more accurate to say that Thompson, having read Spencer and assimilated some of his ideas of social evolution, turned to George and then Bellamy, finally appreciating that only socialism could resolve the contradictions inherent in an eclectic radicalism that too often relied on panaceas like the single tax.

More critically, Thompson was a talented left-wing writer of popular verse and compiler of the well-known Labor Reform Songster (1892). One of his more memorable rhymes was “The Political Economist and the Tramp,” first published in 1878. It was a direct attack on the “scientific school” that Thompson clearly stipulated included both Adam Smith and Herbert Spencer. McKay fails to mention that this “brilliant satire” even touched down on Spencer, let alone that it was aimed decisively at him. Instead, Thompson’s verse is presented by McKay as being directed at the “hypocrisies of … laissez-faire liberalism,” which McKay associates with the Canadian writer Goldwin Smith. (RO, 116) Indeed, in reading McKay on Thompson, the substance of Reasoning Otherwise presents a view of how Spencer is always draw upon, quoted, and used to systematize a “moment of supersedure.” Phillips Thompson, for McKay, echoed “Spencer’s evolutionary law.” It is necessary to read the footnotes carefully to find a reference to Thompson’s socialist repudiation of Spencer in the Labor Advocate in 1891, but this “major critique,” oddly, goes unquoted. (RO, 92, 547, fn. 44)

If we jump ahead a generation or more to the Winnipeg upheaval of 1919 we encounter the last gasp of McKay’s first socialist formation. The show trials that followed in the wake of the General Strike saw many charged with ‘crimes against the state’. Two leftists, in particular, are discussed by McKay. Fred Dixon and W.A. Pritchard found themselves in the docks, charged with sedition, seditious libel, seditious conspiracy, and other transgressions – what McKay designates offences “against world liberal order.” The speeches of Dixon and Pritchard before the jury McKay considers to reveal much about a variety of thinkers, among them, of course, Herbert Spencer. Pritchard, according to McKay, was more the “visiting speaker in Spencerian sociological theory” than was the homespun Dixon. (RO, 500, 508) In actual fact, the published trial addresses of these two Winnipeg 1919 martyrs reveal only a very few passing (rather inconsequential) references to Spencer, within texts that fairly drip with copious citation of a long list of named eminent thinkers. McKay’s reconnaissance is thus at times itself in need of reconnaissance.

IV

The heart of McKay’s Reasoning Otherwise consists of four lengthy chapters on what he considers were the four “great questions of the Canadian left”: class, religion, woman, and race. (RO, 430) Leftists in the 1890-1920 years might not have agreed with McKay’s assessment. I doubt they would have ranked the ‘woman question’ on a par with other issues. And race did not concern them nearly as much as other matters. They would almost certainly have considered ‘the economy’ and its ‘rulers’ to have been a central question, as evidenced by the significance of Gustavus Myers book, History of Canadian Wealth (1914). Also great was the left’s attention to war, a concern which had been growing in English-speaking revolutionary circles since the Spanish-American War and the Boer War ushered in a new century. It certainly merits questioning why McKay does not either end his coverage of the first formation of Canadian socialists around 1910, or at least consider war and peace in detail alongside class, religion, gender, and race. But all of this is far less important than the broad terrain RO traverses, doing so with attention to subjects that the contemporary left will immediately grasp as fundamentally important.

Homage to the R-34 (1967-68) detail.

Enamel paint on plywood and steel, 2.95 x 31.54 x .025 m overall, National Gallery of Canada (NGC_.39705.1-26E) ŠThe Estate of Greg Curnoe

McKay’s chapter on class addresses less how his first socialist formation grappled with the complexities of social stratification than what constituted the organizational, intellectual, and political body of the broad left in the years from 1890-1920. To be sure, there are extremely useful accounts of the ways in which socialists struggled, for instance, to understand the agrarian west as “one giant factory, whose roof-tree is all out doors,” a pivotally important insight put forward with vigour in Alf Budden’s 1914 pamphlet, The Slave of the Farm. In outlining the contribution of these kinds of writings, McKay sketches for us the ways in which Canadian revolutionaries of the early 20th-century contributed to an understanding of the peculiarities of the country’s class formation, which, in turn, helps to account for how and why radicalism became rooted in particular political economies. (RO, 204-205)

The chapter on the class question is, however, really a tour de force in terms of its bringing together the histories of various organizations of the left (Socialist Labor Party, Canadian Socialist League, Socialist Party of Canada, Social Democratic Party of Canada, a variety of Independent Labor Parties, the One Big Union, the Industrial Workers of the World), the publications they spawned (Cotton’s Weekly, Citizen and Country, Western Clarion, Winnipeg’s Voice), and the often locally based leaders who serve, for McKay, as representative figures of the diversity inherent in Canada’s first left formation. This is done almost unconsciously, for McKay, as I have said, is really not interested in the left’s history of organization, but what emerges is nonetheless an invaluable institutional overview. Throughout the chapter, McKay weaves back and forth across differences distinguishing elements of the left, always massaging them into less significance than they have been accorded by past writers. Given his argument about the need to situate leftists within one formation, he is of course prone to downplay what separated varieties of socialists programmatically, and McKay succeeds, to some extent, in conveying that on the class question there was much that invariably brought Canadian leftists together, even if they did not experience anything approximating ‘party unity’. In what is undoubtedly one of the richest 100-page overviews of Canada’s early socialists, the “often confident, lifelong, unbendable, intransigent, and formidably self-educated and self-motivated exponents of reasoning and living otherwise” had done invaluable work in “demanding a public sphere in which the class question could be debated and new classless futures could be projected.” (RO, 211)

Yet it is difficult to shake off the conventional wisdom that somehow Socialist Party of Canada activists, the much-maligned so-called sectarian impossiblists, were, contrary to McKay’s suggestions, different in their reasoning and acting than their counterparts in the Canadian Socialist League or, later, the Social Democratic Party of Canada. There is, in this foundational chapter on class, both a sense of what McKay’s elastic method can bring into heightened relief and a hint of what it is masking. On the one hand, stepping back from the interminable disputes associated with various strains of left thought does indeed reveal a picture of oppositional cadre more coherent and capable of intervention in the politics of everyday life than has previously emerged. On the other hand, for all of his capacity to assimilate differences, filing down the rough edges of distinctive and often incompatible approaches to issues of importance such as how to involve comrades in the electoral process, the trade unions, and the recruitment of new socialists to the cause, there is no denying that within what McKay designates the first formation of Canadian socialists, there would be as much disagreement as there was consensus. This hard reality, codified in programmatic statements as well as in the actual practice of particular leftists, emerges more clearly as McKay moves into discussions of religion, women, and race. If McKay’s scorecard registers, after his discussion of the class question, only positives, it soon records some negatives.

McKay’s discussion of the religious question as central to the first formation of Canadian socialists builds on pioneering work on the Social Gospel by Richard Allen and others. It nonetheless approaches the relation of religion and the left from a different angle. Just how figures such as Salem Bland, J.S.Woodsworth, or William Irvine negotiated within a new Christianity a socialist sensibility is important to McKay, but his real concern is to show how debates about and around religion were fundamental to all leftists in the 1890-1920 period. Indeed, it is precisely because of this that Herbert Spencer mattered so much to leftists of this period: his popularization of Darwinian principles and the scientific method posed a challenge to centuries of religious dogma. As Marx understood clearly as early as the 1840s, in the age of revolution and the triumph of industrial capitalism, “criticism of religion is the premise of all criticism.” It is thus not terribly surprising that in this chapter on religion McKay’s scorecard comes out; reconnaissance reveals its polemical turn.

McKay begins his chapter on the religious question and early Canadian socialists by posing the importance of the Christian socialist question, “What Would Jesus Do?” Jesus, according to McKay, would be on the side of liberation, against the privileged, be they in their pews or occupying more secular seats of power. Acknowledging this shows how the question, “What Would Jesus Do?” “took on a revolutionary aspect.” (RO, 239) In all of this, McKay takes us a good way along analytic and investigative paths that need to be explored in the history of Canadian socialism, identifying those leftists who lived otherwise guided by their understanding that socialism was “applied Christianity” as well as their radical counterparts who deplored the influence of “sky pilots” and the “medieval mildew” of religious mysticism.

This is done with a certain polemical flair. Religious historians and their perspectives are discussed with a measured, if critical, reserve. Labour historians (none are actually cited) have a rougher ride. They are given the back of McKay’s religiously-sensitive hand: their “thinly veiled contempt” for the “Christian socialists” of the Victorian and Edwardian eras is presented as a consequence of seeing such people as “middle-class meddlers, pious preachers, or at best the mediocre warm-up band for the real revolutionaries who followed them.” (RO, 219)

As McKay notes, many early socialists were central players in what amounted not only to an attack on all organized religion, but an uncompromising rejection of the notion that God existed. Militant mobilizations in the sphere of production and heightened promotion of class struggle in circles like the Industrial Workers of the World corresponded to a crescendo of critique that mocked the hypocritical and complacent nature of all churches and assailed the possibility of any God. “A Christian cannot be a Socialist,” declared Toronto’s Socialist Party of Canada soapboxer par excellence on the religious question, Moses Baritz, “and a Socialist cannot be a believer in Christ or God.” (RO, 251-252)

McKay’s scorecard marks down disapproval with these anti-religion revolutionaries, who he thinks fell too easily into the trap of being condemned by right-wing propagandists as “atheists,” the denunciation tarnishing socialism’s broad appeal. Since Canada was a religious liberal order, he seems to be saying, it was best not to push the envelope too far, lest one burn in the everlasting hell of political marginalization. In my view, McKay is unduly critical of these atheistic socialists, too quick to relegate them to the outer limits. Arguably the most significant African American socialist of this era, Hubert Harrison (who incidentally learned much from Spencer), considered progressive and socialist thought in the pre-World War I years to be summed up in two characteristics: militant unbelief and democratic dissent. There is also in McKay’s reading of a progressive Jesus insufficient attention to the residue of reaction Christianity often constituted in some of its varied guises, many of them bearing no relation to the Social Gospel and Christian socialism. This, as the anti-God socialists of these times knew all too well, layered the lives of workers.

McKay quotes one such advocate of militant unbelief, Ottawa’s Percy Rosoman, whom he describes as “fire-breathing,” likening his polemical article in a 1910 issue of the Western Clarion, “Socialists vs. So-Called Socialists,” to the “fire and brimstone denunciations of his clerical enemies.” For McKay an all-out assault on religion was never what socialism was truly to be about, even though there were plenty of socialist agitators who thought and acted otherwise, and not without reasons. Rather, what socialists should have been doing is what McKay himself prefers that they had done and what his reconnaissance then constructs as the actual history: “The point was not that religion should be abolished. It was that the questions it raised and the positions it proposed should be part of a democratic public sphere, open to rationale debate, and not enforceable by the confessional, the heresy trial, or the coercive power of the state. Implying that socialism meant just one position, and a bullying tone of voice that shamed those who did not hold it, were hardly fulfillments of the ideal of deliberative democracy in the sphere of religion.” (RO, 247-248) McKay’s scorecard is unambiguous in its deduction of ‘points’: “Focusing on atheism as a core principle in socialism itself was in error.” (RO, 259)

It is not all that surprising, then, to find oneself at the end of McKay’s chapter on the religious question reading about one of western Canada’s advocates of the early co-operative commonwealth, E.A. Partridge, author of a 1926 text, A War on Poverty, that is hailed as “brilliantly visionary.” (RO, 272) This remarkable text, McKay tells us, constituted “a burning coal of righteous justice to be passed on to the new socialism taking shape under that vast Prairie sky wherein he saw the face of God.” (RO, 278) Amen to that, a secularist socialist might say with some relief.

As McKay moves from class and religion to women, similar things could well be said. The chapter on the woman question contains new material on the specific involvement of women in socialist campaigns, commencing with a discussion of the 1902 candidacy of Margaret Haile, a socialist running for political office before women even had the right to vote in Ontario. It outlines women’s involvement in socialism, how ‘the woman question’ ranged broadly across issues associated with waged work, domestic labour, marriage and the family, patriarchy and sexuality. Proclaiming the need to build a post-polemical inclusive history of the left, this chapter actually engages critically, at times polemically, with much of the established literature. McKay differs with feminist historians such as Linda Kealey and Janice Newton (especially the latter), with whom he disagrees as to the extent to which women in the left of this period were suppressed, subordinated to male leaders, and relegated to secondary roles within socialist organizations.

Homage to the R-34 (1967-68) detail.

Enamel paint on plywood and steel, 2.95 x 31.54 x .025 m overall, National Gallery of Canada (NGC_.39705.1-26E) ŠThe Estate of Greg Curnoe

McKay’s claim is that while he does not deny “the opposition confronting socialists feminists” within what he calls the first formation of 1890-1920 his method is better able to capture the range of achievements of men and women on the Canadian left, “restoring more complexity and agency to the first formation’s gender politics.” McKay’s elasticity allows him to eschew a “narrow focus on the institutions of the left,” so that he is able to give adequate acknowledgement of “a much more interesting, original, and boundary-busting socialist-feminist movement.” (RO, 288-289)

It may also allow him to understate and sidestep much. Some socialist women’s discontent with how they and the issues they embraced had been relegated to the periphery of their own movement registers weakly in McKay’s account. For someone so committed to a textualist take on early Canadian socialists, addressing time and time again the books that constituted ‘the library’ of leftist thought, McKay is able to brush aside troubling titles like R.B. Tobias’s and Mary E. Marcy’s Women as Sex Vendor, or Why Women are Conservative (Being a View of the Economic Status of Woman) (1918). Such writing had a particular resonance with the sense of ‘radical manhood’ evident in the Industrial Workers of the World, whose disdain for the ‘homeguard’ often expressed a distrust of female capacity to ‘domesticate’ male militants. E. Belfort Bax, a socialist whose titles included The Legal Subjection of Men: A Reply to the Suffragettes (1908) and The Fraud of Feminism (1913), is too easily relegated to the status of a non-player in the making of socialist sensibilities on ‘the woman question’.

The subjective selectively of McKay’s reconnaissance is thus unmistakable. He revels, for instance, in a particular reading of Engels’ The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State, accenting what is presented as the book’s “quietly hilarious send-up of the dire tedium of heterosexual bourgeois marriage.” Addressing Engels’ insistence that when capitalist property relations disappear new gender relations would invariably arise, constituting a freedom of sexual union premised on something other than male economic power and female fear, McKay writes: “That the most convincing models for such a ‘free monogamy’ are to be found in the contemporary gay community – a sexual minority ridiculed by Engels – suggests that the Founding Father’s economic determinist analysis could not grasp, by a long shot, all that went into the subordination of women by heterosexual men.” (RO, 292-294, 580-581) In its time, venturesome commentators on “love’s coming of age” and male comradeship/fellowship, like the “Uranian socialist” Edward Carpenter, read Engels’ Origins, for all of its flaws evident to late 20th-century readings, with more sympathy than McKay can now muster. They even seemed to learn and benefit from the book.

McKay’s treatment of socialism and sexuality can be productively contrasted with his discussion of the religious question. There, as I have suggested, McKay was critical of those socialists who assailed God and crucified all religion on the cross of antiquated superstition. Yet as he acknowledges, “Charges of atheistic socialism paled in their effectiveness beside those of ‘free love’ and ‘family smashing’. “Vote for the socialists,” McKay comments with respect to how this socialist sex radicalism was assailed, “and wait for the moral maelstrom.” Yet McKay clearly has far more time for the sex radicals who got directly in the face of the early 20th-century equivalent of ‘the moral majority’ and the ‘family values’ crowd than he does for the anti-religious radicals who assailed the guardians of God. (RO, 315) McKay’s reconnaissance, in short, does indeed have its scorecards. “Bubbling over with dissident thoughts about sexuality and marriage,” McKay presents socialists for whom the woman question was a perennial subject of lectures, writings, and parlour discussions as doing their part to unsettle certainties and turn ossified, rock-hard ‘social truths’, with a long history of contributing to oppression, into new arenas of discussion and possibility. (RO, 316, 323) They were successful, in McKay’s words, in “rooting the woman question in Canadian politics.” (RO, 341) No matter that they tilted their gender-bending sails into the gale of sexual convention. But this generosity of spirit is not extended to the atheistic socialists. Did not the harsh critics of religion achieve something in the long Canadian battle to separate church and state and win workers and others to new ways of rational thinking?

Something similar, but also considerably less, happened with socialists and race. Conventional wisdom relating to the left and the race question suggests that before 1920 socialists subsumed race into class, arguing that racial oppression could only be overcome through the emancipation of the working class as a whole. This, of course, was also the position that many on the left took to the woman question, including some intelligent and intransigent women agitators. As McKay shows, in the making of early Canadian socialism, race was grappled with but not quite as forthrightly and as sensitively as was gender or religion. The race question, moreover, embodied even more complexity than did the woman question, encompassing the social construction of racial difference, issues of immigration, ethnicity, colonialism and imperialism, as well as, finally, ‘the nation’.

In many ways McKay’s chapter on socialists and race in the 1890-1920 period is the least satisfactory in the book because it necessarily addresses so much on which the left actually accomplished so little. McKay relies heavily on specific illuminating events, like the famous 1914 Komagata Maru incident, in which approximately 375 Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs tried to decamp from a ship and enter Canada at Vancouver, only to be refused landing. Amidst racist cries of “White Canada Forever!” Socialist Party of Canada activists were rare advocates of the Punjabis who aspired to Canadian citizenship, and a ‘Sikh-Socialist’ united front crossed borders and spoke in the language of a true ‘International’.

As racism boiled on the west coast, many Canadian socialists were but a few faltering steps removed from the racialized project of ‘building the nation’, rooted as it was in notions of whiteness as the pivot on which civilization and progress turned. If organs of socialist thought and left critique, such as the Western Clarion, might poke jocularly at the pretensions of Empire, and rage against capitalist imperialism, they were far less likely to question racism, challenge racial stereotyping, and take direct aim at the extent to which Canada as a nation had been forged as a colonial project of white settlement premised on Aboriginal displacement and dispossession. The labour movement was too often compromised in its demands of immigration restriction, rooted as they were in racist conceptions of Asian peoples and chauvinistic prejudice toward white ethnics from Eastern and Southern Europe.

McKay weaves through this minefield with sensitivity and often clearly articulated regret. He explores the ways in which immigration fuelled the first formation, with diaspora socialism – leftist newcomers from Finland, the Ukraine, and the Jewish ghettoes of Eastern Europe and Russia – contributing mightily to the ‘foreign language federations’ of the emerging Canadian left. If there are moments when McKay is prone to see the racial blind spot in too bold relief – he criticizes the Socialist Party of Canada theorist E.T. Kingsley for denouncing the region north of Lake Superior as “worthless,” a land “shunned by about every animal … except that brilliant specimen, the wage slave” on the grounds that it slights Aboriginal peoples – he is rightly insistent that many Canadian revolutionaries were anything but radical on the race question. In many ways, this last chapter on race is an expression of the limitations of early Canadian socialism. As Mark Leier has noted pithily, socialism was no vaccine against racism.

V

This long exploration of “the people’s enlightenment” culminates in what McKay identifies as “an organic crisis of liberal order.” With World War I, the Russian Revolution, and the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919, a crisis of hegemony ensued. The people (who McKay fails to note sufficiently were in fact anything but universally drawn to the project he designates ‘reasoning otherwise’) demanded of liberal order a variety of democratic fulfillments. McKay moves out of the traditional conservatism of accounts that see in the General Strike a collective bargaining battle gone ballistic, in which the state overreaches itself in repression. He reads into the conflict much more, presenting a rich tapestry of argument about science and social struggle, democracy and citizenship, and refusals of power. McKay presents all of this as threatening to give rise to a “new political order, a new historical subject, an answer to the liberal leviathan.” Along the way, McKay’s historiographic scorecard bestows points here, deducts them there, as we would expect. (RO, 528)

Homage to the R-34 (1967-68) detail.

Enamel paint on plywood and steel, 2.95 x 31.54 x .025 m overall, National Gallery of Canada (NGC_.39705.1-26E) ŠThe Estate of Greg Curnoe

For the most part the account is one with which any contemporary leftist will be in agreement. McKay nonetheless overreaches himself. A few specific examples will suffice. They underscore the extent to which, in a book of this detail and length, the decisive and indeed formation shattering influence of the Russian Revolution and the creation of the world’s first workers’ state is understated in McKay’s account. This is not unrelated, as well, to the centrally important issue of World War I and the response to it by the world socialist movement, which fractured into two opposing camps: the overwhelmingly dominant socialist patriots, who aligned with their own ruling classes and signed on to the ‘war effort’; and a minority of anti-war socialist internationalists, some of the staunchest of whom were aligned with the Socialist Party of Canada or members of Lenin’s Bolshevik Party. War and revolution, in the years 1914-1917, rewrote the script of reasoning otherwise. McKay’s reconnaissance suggests to him something different in what he regards as the moment of supersedure that was Winnipeg 1919.

Rather than understand the mobilization of resistance that constituted the 1919 Winnipeg upheaval against this tumultuous global background, in which the dissolution of the socialist Second International (1889-1916) as war and the Bolshevik seizure of power fractured the left and galvanized new and counterposed ways of thinking and acting otherwise, McKay locates Winnipeg 1919 within his own reconnaissance. He strains too obviously to establish the unique interpretive meaning of what Winnipeg 1919 constituted. One measure of this is his nationalist penchant, evident at other times in RRR and RO, that declares Winnipeg 1919 to have been “an event unlike any seen before in North America.” (RO, 495) Perhaps, but it is equally possible to argue that the Seattle General Strike, which preceded the events in Manitoba by a few months, contained much of parallel significance. Revolutionary developments in Mexico, over the course of 1910-1920, while undoubtedly different in the ways they unfolded, can hardly be sidestepped so easily in a treatment of ‘reasoning otherwise’.

McKay perhaps also extends too far when he argues that not only was the Winnipeg General Strike “a massive class struggle,” but that it became a “defining moment of the ‘Christian Revolution’.” His evidence for this questionable assertion is that Winnipeg’s Labor Church was a central institution in the unfolding struggle, that the Labor Church services constituted the largest and most memorable meetings of the strikers, massive Victoria Park “teach-ins” that were “performances of socialism on a scale previously never before witnessed.” (RO, 469-470)

Such a reconnaissance may well mistake the timber of Christian Revolution for the bright fall foliage of a Labor Church that was itself, while important, less of a structure than an ideal, and a passing one at that. The vision of a new Christianity, centred in bodies like Labor Churches that promised a salvation linked to socialist aspirations, was certainly an important feature of the landscape of dissident thought and social activism in the pre-1917 years. But the Labor Church was also given great stimulation by the radicalizing initiatives of 1917 and by the subsequent class upheaval of 1919 itself, the very forces that would sound its deathknell. McKay’s sense that the Labor Church played a pivotal role in the unfolding revolutionary drama of 1919 may well interpretively mistake what was happening. The Winnipeg General Strike certainly established a stage on which bodies as loose and eclectic as the Labor Church could function as forums, and religious allusions emanated from platforms, but were they the defining element of the upheaval? W.A. Pritchard spoke, for instance, of the “so-called Labor Church,” and one reason he may have used such language was to note the extent to which this body was less of a concrete, influential entity than McKay is trying to suggest.

Finally, McKay’s reconnaissance insists that the Winnipeg General Strike, as the performative enactment of socialist possibility, needs to be understood as an ongoing success, reaching out to us in its lessons and meanings. In this he is undoubtedly right, and others have made similar claims. But this reconnaissance is again one-sided. The left also needs to understand the limitations of the General Strike and 1919. McKay refuses to acknowledge that the struggle was indeed defeated, that for all that has survived of Winnipeg 1919 in the DNA of Canadian working-class struggle and socialist politics, there is now a great deal to be learned in assessing what went wrong. This must be part of any ultimate reckoning that goes by the name of reconnaissance. The celebration of 1919 as struggle is, surely, enshrined in the left; its memory is not really in danger of being erased.

Central to this questionable interpretive one-sidedness is McKay’s suggestion th at Tim Buck, arguably one of the world’s longest-standing Stalinist leaders, and head of the Canadian Communist Party through many decades, had gotten his take on Winnipeg 1919 very wrong. Buck wrote, in a 1960s reflection on Canada and the Russian Revolution, that “the grim truth is that the Winnipeg General Strike exposed the fallacy of the theory that: ‘The workers can make themselves invincible by simply folding their arms’. That strike marked the high point of that false theory in North America and, simultaneously, the beginning of its decline.” (RO, 494-495)

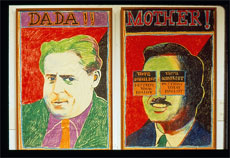

Dada/Mother (1964)

Oil pastel on newsprint, 134 x 89.3 cm (each). McIntosh Gallery. ŠThe Estate of Greg Curnoe

Tim Buck is certainly a Canadian revolutionary leftist with much to atone for. But in this case his assessment was far more right than it was wrong. The struggle in 1919 foundered for many reasons, but one part of what went wrong was an inadequate appreciation of the forces that would be marshalled against it, including the powerful capitalist state. There was, in the general reasoning of Canada’s left of this so-called first formation insufficient attention to the structures of resistance that were desperately needed if all that 1919 constituted was to be sustained. Gramsci, on whom McKay relies selectively, knew this well. As much as he would, in 1919, be convinced that the Canadian workers of Winnipeg were on the right track, in retrospect he would have had to agree with Buck that they also failed to grasp much of what they needed to know to win.

VI

In a sense, that is the essential contradiction at the core of McKay’s important book, which stands as an undeniable achievement. Revolution is not evolution: it is neither organically constituted nor inevitable. Thinking and living otherwise, as human endeavour within individual parts of a social organism, will not, in the end, transform something as powerfully entrenched, deeply debasing, and egregiously unjust as capitalism. Reasoning otherwise is indeed the subjective starting point of all struggle. But such oppositional thought can not, historically, be abstracted from the collective action, the building of institutions and mobilizations of resistance, and, ultimately, the structures of change that are capable of overturning the consolidated, institutionalized force that constitutes a system of exploitation and oppression. We make socialists as we think otherwise. We make socialism as we overturn capitalism and substitute our agency for that of those who stand against solidarity and human welfare and embrace the counterpoised ‘market’ values of individualism, exploitation, and profit.

Doing otherwise is the ultimate act of transcendence. It is the difficult leap into socialist possibility that can only be accomplished by overcoming the historical deficits of the left’s long past. Taking a run at this means overcoming the limitations of loose ‘formations’ of generalized left opposition that have long been the resting place of the tragically fragmented forces of revolution, their divisions and accommodations isolating those who reason otherwise from the power that needs to be usurped from the capitalist enemy and wielded in the interests of humanity.