Feeding Percy (1965)

Oil, lightbulb, Perspex, and electrical wire on wood. 190 x 166.4 cm. ©The Estate of Greg Curnoe. Collection of Museum London, Art Fund, 1966

MYTHS AND LEGENDS abound when it comes to the sixties. These times have been heralded as a period of great popular mobilization, when people did not hesitate to sacrifice themselves for the cause of the coming revolution and were continuously marching in the streets, singing protest songs, and shouting political slogans. I have grown up with these memories of street battles and public confrontations. I have lived surrounded by images of peace rallies, acts of civil disobedience, and love-ins. I have seen innumerable posters of Martin Luther King, John F. Kennedy, Daniel Cohn-Bendit, and Che Guevara. Those were the days, I have often been told, when people did not hesitate to face state oppression and right-wing intimidation to foster a better world for themselves and their children.

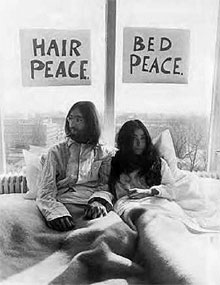

As grandiose as it may sound, this historical narrative does not encourage but rather deters mobilization today. It demoralizes actual political initiatives. Whatever the new generation does, it never seems enough. Whatever the current definition of a struggle’s objectives, or the size of a contemporary rally, or the outcome of today’s protests, it seems as if it can never measure up to the sixties’ glorious past. In this regard, the sixties cast a depressing shadow on the present. I have been reading newspaper clips on John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s bed-in and I am struck by the incredible nostalgia that penetrates journalists’ account of the event. Compared to the baby-boom generation, today’s youth always seems apathetic, conservative, and depoliticized. The glory days, or so goes the dominant discourse, are forever behind us. Never again, we are led to believe, shall we enjoy a moment of popular communion and public upheaval as great as the sixties.

I must confess that I believed this interpretation of Quebec’s history when I started studying that decade a few years ago. In 1969, I was not yet born. I was not a witness to these heroic and exhilarating times. I had no reason to doubt others’ recollections of their younger days. I had a genuine interest in knowing more about a period when revolution was in the air, when the Civil Rights Movement dramatically challenged the American status quo, when, here in Montreal, the Quiet Revolution was redefining the place of Francophones and Anglophones, when the quest for peace opened people’s eyes to the great horrors perpetrated around the world in the name of a tainted Soviet or American democracy.

I was fascinated by archival clips of street protests, peaceful building occupations and strikes, and equally intrigued by the sixties’ failure to really challenge the liberal system. How, if the sixties were so buoyant and unanimous, did they fall short of their dreams, ending in the United-States with the election of Richard Nixon and in Quebec with that of Robert Bourassa? What went wrong? What happened between 1969 and 2009 that created such an apparent appeasement of North American youth? Where did all the rebels go? Why did the 1967 summer of love and the 1967 Montreal Expo not lead to more love-ins, more sit-ins, and more bed-ins?

I was asking myself these questions – and many more – when I decided to work on the sixties in French-speaking Quebec. But these questions rapidly evolved once I started the writing of my book, Une douce anarchie: les Années 68 au Québec (2008). The results of my archival research and numerous interviews shattered many of my preconceived ideas.

Let me reassure every reader. I did not find that the sixties youth were not politically active and did not provoke some important and long-needed change in our society. The reality is that from 1967 to 1970 something happened that fundamentally transformed the old French-Canadian social order inherited from the war. Not only the more visible aspects of society changed (for example, the way people dressed or the way they cut their hair): the very collective psyche was translated into a new language. When, coming from the fifties, you attend plays written by Michel Tremblay, spend a night at the Osstid’cho, read the latest edition of the countercultural magazine Mainmise, listen to records played by the Quatuor du Nouveau Jazz Libre du Québec, visit the annual exhibit of the art students at the École des Beaux Arts, start a discussion with the young intellectuals distributing flyers and revolutionary literature at the entrance of UQAM’s Pavillon Read, you know that something has forever changed.

The sixties in Quebec cannot be summarized in one or two sentences. They are multifaceted and multilayered. Given this complexity, I shall proceed systematically, underlining three aspects of the sixties that, in my view, have been too often overlooked. In a way, the sixties are a myth. This agitated decade corresponds to the foundation of our modernity, to its golden age. It is filled with heroes and their prowess, glory and fame, titanic battles and undying victories. The very celebration of John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s bed-in, which became an exhibit that opened in April, 2009, at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, testifies to this mythical dimension. These two singers are officially recognized by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts not for their visual artworks but for a political “performance”, staged in the room of a Montreal hotel.

John Lennon and Yoko Ono “Bed-In,” Montreal, 1969. CBC Archives

A myth always shows two sides. On one side, it instils a sense of purpose to people’s activities and galvanises their hopes and dreams. It gives society a history and provides a horizon. As such, a myth proves very useful. No society can exist without myths. On the other side, a myth hides what society does not want to reveal itself. It serves as a mask. It tells the story that most people want to hear but never the whole story. For example, in the fifties, French Canadians entertained the myth of forming a more spiritual nation living amidst a sinfully materialistic North America. The myth might have been noble and inspiring to some. But it veiled the fact that French Canadians were unwaveringly poor.

The myth of the sixties also shows two sides. On the one hand, it helps to recall that society is a manmade product, that history is not governed by providential laws – that fighting for justice can be its own reward. It gives people the drive to always strive for more, always expect better, and never settle for less. But, on the other hand, the myth of the sixties fails to insist on the profound connection that exists between counterculture and North American consumer society. Also, it provides the picture of a unanimous youth fighting side by side against an oppressive system, when in fact the sixties activists always were a small minority. Finally, it gives the impression that people’s capacity to mobilize and fight primarily rests on their willingness to do so, as if the sixties were not embedded in a specific social context.

These are the three aspects of the sixties that I want to write about. In the first part I explain how the sixties counterculture corresponded to an emerging youth culture, and how this emerging youth culture was not deeply threatening to the prevailing consumer culture.

In the second part, I show how statistically marginal Quebec activists were forty years ago. It is simply not true that everyone participated in the global and local political debates of the sixties. As surprising as it may sound to some, most observers in 1969 were complaining about the young generation’s lack of interest in politics.

In the third and final part, I situate the sixties with respect to the structural changes that affected Quebec society. I show how activism was then linked to specific social conditions and not to people’s inner and spontaneous desire to change the world. It is no coincidence that so many oppressed groups came out of the shadows in the sixties. Colonised nations, French Canadians, Women, Blacks, Indians, everyone seemed at once to get the word that their time had come. This simultaneity can be explained by looking at the social transformations affecting North American societies. Something was happening within the very functioning of the liberal system that made revolt possible, and even welcomed.

I Counterculture or Consumer Society?

In the sixties, youth culture definitely was a counterculture. Confronted with the scandal of the Vietnam War, many young Quebeckers responded by pressing the need to develop a culture of peace. Faced with the growing rationalization of production, they demanded the humanization of work. They adamantly refused to accept the current order of things that transformed citizens into merchandise and everything else into natural resources.

In a widely read manifesto published in La Presse and Le Devoir in October 1968, Réal Valiquette, a college student, called for the complete transformation of Quebec’s economic and social system. He asked his generation to help him vanquish the society in which they lived. The young author no longer wanted to obey everybody’s orders but his own. What he wanted more than anything to express in life was himself – his desires, his fears, his tastes, his whims. Quebec society, claimed Valiquette, could not provide happiness because it was designed to turn people away from their individual aspirations. Of what good would it be to work toward the perfection of society’s efficiency if it meant to lose oneself in the process?

Réal Valiquette was not alone in advocating a complete overthrow of the dominant order of things. Many people of the same age were fed up with a system that condemned them to repeat outdated lessons and replicate disconnected ideas. To eliminate this pernicious state of obedience and indoctrination, they argued in favour of a complete overhaul of the values and rules that prevailed in the province. Everything had to be new: in literature people spoke of the ‘nouveau roman’, in cinema of the ‘nouvelle vague.’ Whatever the domain, it seems as if everyone wanted to be part of the avant-garde.

In the late sixties, of course, the ideology that pervaded progressive circles was the ideology of the New Left. Marx (revised by Marcuse) and Freud (revised by Wilhelm Reich) were the master thinkers of the day. They taught the need to create a materially and culturally decolonized society without following a top-down bureaucratic approach. For them, revolt was “a matter of physical and mental hygiene,” and each individual had to reclaim the personality he or she had delegated to an anonymous and mechanical system. Living in a society that only underscored wealth and efficacy, the solution was not to continuously render the system more profitable and productive but to sever every link with the rationalist principles that served to legitimize it. Of course, poverty still plagued many Quebec neighbourhoods and French Canadian workers continued to be, as Pierre Vallières abruptly put it, the “White Niggers of America”. But the promise of an affluent society was drawing near. Sociologists were talking about the coming of a leisure society. Never before had Quebeckers been so rich, enjoying the luxury of television sets, automobiles, bungalows, and frozen dinners. But this newly gained wealth had a price: French Canadians who had lived in close-knit communities were more and more isolated. They had rejected religion but had not yet found a way to give meaning to their suburban lives. They had acquired gadgets and knick-knacks but could not find personal fulfilment in their possessions. As Mick Jagger put it in 1965, they couldn’t “get no satisfaction.”

A poll conducted in 1967 by the Jeunesse étudiante catholique found that the prevailing sentiment expressed by high-school students in Quebec was boredom. Their existence seemed empty. What these students demanded was not more material goods. What they wished for was individual happiness. They advocated more self-expression. Their denunciation of exploitation was less strident than their critique of alienation. In comparison with their parents, who had lived through the Great depression, they were relatively well-fed and well-dressed. They lived in decent apartments. What they lacked was the capacity to live one’s dream without suffering any constraints or compromises.

The sixties revolt therefore could bypass any precise ideology. It did not have to formulate a coherent and informed program. Logic and abstract knowledge were not considered compulsory elements of the people’s rebellion. On the contrary, as an anonymous author, writing in L’Antenne, a journal of Cégep Édouard-Montpetit, stated well in November 1968, “What would replace our Cartesian, Judeo-Christian, capitalist mentality would be an “intuitive” mentality with which we would capture the world with our gut.” People had to escape from the prison of rationality and efficiency. They had to enter into their spirit, into their soul, into their core, there, deep down. They had to find the revolution within themselves. “The revolution is in your head”, wrote one Quebec author. “You are the revolution.”

Individually, one by one, by slowly deserting an intolerable system of mass production, Quebeckers could reorganize the world according to their true emotions and desires. Was not the Village (a perimeter delineated by the Parc Lafontaine, Avenue Des Pins, Sherbrooke Street, and Bleury) the concrete experimentation of a different sociality? Was it not – as in Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco – a place where freaks and rebels could get together to celebrate the wisdom of the new age? In the vicinity of the Carré Saint-Louis, Montreal’s bohemia could find smoky cafes, an underground network of information, anti-conformist boutiques and shops, a citizens committee, and so on. At Gaspé, the Maison du pêcheur libre represented another example of a well-known commune before it was closed down by the police. There, in this former fisherman's shack, artists, anarchists, felquistes, and hippies shared a common belief in the coming collapse of the capitalist system and in the ability of their anti-conformist attitude to really change the world.

As everybody knows, the sixties’ distinctive youth culture is characterized by the popular expression “Sex, Drugs and Rock & Roll”. It is, as the 1968 motto went, by consuming drugs, by freely making love, and by listening to records by their favourite rock musicians that people could reveal themselves as a new humanity.

At the end of the decade, the use of drugs was spreading among Montreal bohemians. For those who were spending their nights in bars on St-Denis or St-Laurent, marijuana, “goofballs,” and LSD offered a chance to access new zones of mental consciousness. In a novel which takes place in 1969, Marc André Poissant described the climate which permeated one Montreal cegep (College d’enseignement general et professional). His main character, Paul Désormeaux, a college student, feels a great personal void. André Dion, a member of a Marxist-Leninist organization, tries to convince his friend Paul to step out of his sombre mood, but Paul prefers to succumb to the pleasures of artificial paradises. He finds in these illicit substances a way to acquire an unexpected lucidity. Trying diverse drugs, from marijuana to acid, he plunges deeper and deeper into this parallel universe. His musical tastes rapidly go from Bob Dylan, to the Beatles, and then to Jimmy Hendrix. He gets interested in oriental philosophy. His journey illustrates that of many members of Paul’s generation – although we are far from describing a general conversion of Quebec youth to the pleasures of dope. According to a study conducted during the summer of 1968 (noted in Le Devoir on 24 December, 1968), only 10 percent of high school, college and university students had ever experimented with mind-altering substances (including glue!). Of that 10 percent, half had only tried drugs out of curiosity or to ape their peer-group. In contrast, 90 percent claimed never to have used narcotics and 72 percent asked for tougher regulations against marijuana, a proportion that climbed to 84 percent when it came to outlawing LSD.

Counterculture also accompanied a sexual revolution. In the fifties, the family institution was celebrated and magnified. Marriage necessarily led to procreation. The model of the perfect woman was centred on a cult of domestic felicity. Around the mid-sixties that model began to be seriously challenged. Free love became one the three great emancipating themes of the decade. With the lessening of fear of infectious diseases brought by the progress of medicine and hygiene and of the fear of getting pregnant with the widespread availability of the pill, not forgetting the sudden eclipse of the stigmata attached to sexual relations outside marriage, free love no longer appeared dangerous, problematic or sinful. Some young Quebeckers did not content themselves with the organization of information sessions on birth control; they asked for the total liberation of sexuality. Making love was for them a political act. It was a way to transform the world. Revolution, they claimed, was “a powerful orgasm.” We should therefore not be surprised that they dreamt of a permanent revolution!

Next to narcotics and sexuality, rock was the third major ingredient of the emerging youth culture. In Quebec, where American pop music soon dominated the airwaves, the American hit-parade was almost immediately mimicked by a series of legendary groups such as the Classels, the Baronnets or the Habits jaunes. Yéyé music was still immensely popular but psychedelic rock made important inroads in youth radio shows before the end of the decade and marked a shift from the light-hearted songs of the early sixties. In Quebec, the biggest pop-chart hit in 1967 was “Donne-moi ta bouche” by Pierre Lalonde and, in 1968, “Je vais à Londres” by Renée Martel. But one could feel that the music scene was evolving. In 1969, the biggest hit on French Canadian charts was “Québécois,” played by the ex-Sinners, who had re-named themselves La Révolution française. A year after participating in the Osstid’cho in 1969, Robert Charlebois launched his Quebec Love album. No doubt, the Californian spirit was blowing over the province.

“Fumé – pot,” La Presse, 1 June, 1969

Adopting a certain dress code, listening to Robert Charlebois’s or Jefferson Airplane’s records, smoking joints and freely making love, Quebec youth participated in a peaceful collective rebellion. Dope, sex, and rock showed the distinctive characteristic of being revolutionary without being political. These life habits challenged the limits of accepted norms without demanding an explicit public engagement. Young people could then pretend, without much effort, to be iconoclasts without having to be active in a political organization, sign a political party membership card or read lengthy and dry sociological literature. Rock, dope, and free love created a border with parents and ‘squares’ (they were those who didn’t listen to rock, did not smoke joints, and were faithfully married) and so rock, dope, and free love united the group in a common rebellious identity. They created a seemingly impermeable barrier between their world and the world of adults. By isolating the younger generation from the rest of society, the sixties counterculture reinforced the impression that the baby-boomers announced a new humanity. From third-year high school to the doctoral level, youth now lasted from ten to twenty years, when it had usually not lasted more than two or three in the fifties. How can one not imagine that it could last even longer? Some Quebec students claimed that they would be twenty years old even in their seventies. Another fifty years, they predicted, and they would bury the last elderly Quebecker. In 2009, enjoying drug trips, listening to The Mamas and the Papas, and living in communes, everyone would be young at heart no matter one’s age.

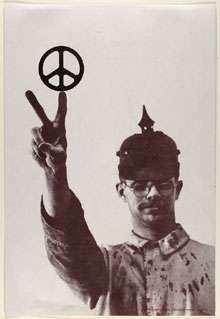

This revolutionary program was perfectly matched for those who wanted to change the world and who, at the same time, wished more than anything that they be left alone. Although counterculture advocated a new beginning (“C’est le début d’un temps nouveau”, sang Renée Claude in 1970, “la terre est à l’année zero”), it was pretty passive. Because the desired revolution was intimately linked to a personal quest, to be oneself was all the people really needed to promote peace and freedom. “Anarchy,” the student Pierre Paiement concluded in October 1969, “is to do what you are, and nothing else.” Staying home doing nothing for a few days could therefore symbolize a radical rupture with the dominant social order for those who believed – as John Lennon eloquently put it – that if only people would stay in bed for a week all wars would end.

Quebec youth was not so much inventing a new society as it was enlarging a student culture that used to be confined to an elite consisting of the sons of doctors, lawyers, and notaries. From high school to university, Quebec students no longer assumed a transitory and precarious status but rather acquired a specific identity for a greater number of years. No longer considered children but not yet accepted as adults, they were placed in-between two stages of life. For those who had the chance to pursue studies well beyond high-school, an original phase of life could begin in which friends played a very important role. No longer children and not yet parents, they spent their days and nights talking with their peers about their future. Of what would the world they would eventually enter be made? Would this world really be tailored for them? Should they accept integration into the labour market and the family institution or should they continue to stay on the fringes of society?

I have already mentioned that, staying in school much longer than any previous generation, young Quebeckers developed distinct social features that corresponded to their specific living conditions. It is important to note that it is these very social features that youth leaders projected as the inspiring model of the future society. They were primarily committed to extending to the rest of the province the conditions which they already enjoyed as young adults. The growing cohort of baby-boomers who claimed that they wanted to invent an alternate social order in fact tried to impose their own existence as ideal.

Far from imagining a completely different world, they reproduced the traits of their proposed utopia from their own way of life. Their future looked pretty much like their present. These youngsters who rejected family life were without children. They criticised work but had not yet entered a career. They denounced any fixed identities and preconceived ideas but did not know who they were, nor what they wanted. Living in communes to save on housing costs, they could imagine a world that was just like a commune and where one’s earthly existence would be consumed by doing what they were already doing: studying, making love, dabbling with marijuana, listening to underground music, living a more or less bohemian culture, strolling in the streets, asking metaphysical questions about the meaning of life, enjoying considerable leisure time, visiting cafes and bars, partying all night. What enabled the youth revolution in the sixties was precisely its uselessness, by which I mean its temporary marginalization from social and economic production. Its critique of the social order could be radical because it was without any consequences. If “freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose,” as Janis Joplin sang at the time, then Quebec youth (deprived of any significant property, childless, and not seeking immediate employment) seemed built to be free!

This helps in understanding why the youth revolt appeared so festive. Mirroring their age group’s expected attitudes, the revolutionary flirtation of the late sixties took the form of a collective happening. Some teenagers declared that they had occupied cegep buildings during the October 68 student strike “to be together.” During the entrancing fiesta of 1968 and 1969, people played guitar, camped in the colleges’ corridors, spit on the bourgeois, debated amongst friends, reshaped the world anew over a few beers. The revolutionary climate resembled that of a giant party. In a September 1969 interview, Réal Valiquette stated: “We have stopped attacking and we have lived in groups: apartments, taverns, popular fairs, [...], etc. We had ‘fun’ everywhere.” According to another student leader, Claude Charron, it was as “if students had been permanently drunk.” This is why the monster rallies of the sixties did not convey any explicit ideological propositions and were not really directed against anything or anyone, except a very nefarious yet nebulous system. In fact, as François Ricard later observed, these manifestations were primarily designed to express the youth’s very existence. They embodied the reality of a surging Woodstock nation.

Beyond this demonstration of strength, it is difficult to uncover any concrete political message. Sincerity and integrity being the norms according to which ideas were now assessed, formulating an ideological platform did not seem crucial anymore. Learning a doctrine was less important than what was coming from the gut. It is, to use the period’s language, because it was ‘fun’ that people gathered and it was because it was ‘plate’ (or ‘dull’) that they protested. Yes, most young Quebeckers were sovereigntists and left-leaning. But beyond all the radical rhetoric they had only a vague idea of what an independent and socialist Quebec would look like. Just like SDS members such as Joan Wallach in the United States, who refused to provide a plan for the future society, Quebec activists, when asked about their course of action, answered that they had no plan, and wanted none. Many activists candidly confessed that they could not care less about what would happen after the overthrow of the bourgeoisie: creativity, they said, would naturally spring out of this joyous destruction. The revolt’s spontaneity was in itself a mark of authenticity.

“We will fight to the end!” chanted the cegepien in the late sixties. But to the end of what, nobody knew and nobody thought that the question was really relevant. Indeed, when one believes that history is marching on and that the new generation is necessarily purer than the “old fogeys,” there is no need to make lengthy speeches. The world that was coming promised to be better than the world it was leaving behind because the younger generation was naturally spreading a spirit of concord and freedom unto the world. The older generation had made Auschwitz and the atomic bomb; the emerging generation would make the revolution of peace and happiness. Besides, it did not bother the young activists much that their future society could prove to be worse than the one they were living in: it was much better to succumb, they claimed, while trying to escape this doomed world than to do nothing and die with it!

II Conservative or Socialist?

If the sixties counterculture was highly critical of the French Canadian tradition based on discipline and respect of sacred institutions (including the Roman Catholic Church and Christian family), it was also enmeshed in the web of consumer society. It was narcissist, soft, iconoclast, and individualistic. Those characteristics help explain why today’s college students can continue to smoke dope, have multiple sexual partners, and listen to the Hives or the White Stripes without threatening the ruling system. This is not to say that the sixties counterculture did not have a positive influence on a variety of spheres, including gender relations, recognition of minorities, tolerance to marginality, environmental concerns and so on and so forth. I simply wish to show another side of the question. In that sense, one may say without erring that the sixties counterculture has both failed and succeeded in its attempt to change the world.

The second aspect of the sixties myth touches upon a somewhat quantitative dimension. How many people participated in the sixties revolt? Seen from 2009 it seems that, forty years ago, the entire province was involved in the struggles for greater civil liberties and the ongoing rallies against the Vietnam War. The story we often hear is that of a united generation raising its fist in the air and proclaiming the reign of freedom and equality for all.

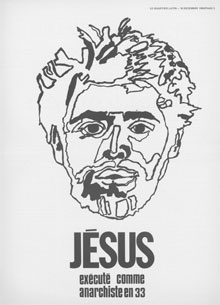

"Jesus – Anarchiste". Poster distributed by Union générale des étudiants du Québec (UGEQ) in 1968 . Le Quartier Latin, 16 December, 1968

My research has taught me otherwise. This, I must confess, was perhaps my biggest surprise. Far from being rebellious, those born in the aftermath of World War Two appeared surprisingly docile forty years ago. If, in the fifties, some conservative observers had described North American youth as a group that revolted without any reason (just think of the movie Rebel Without a Cause, starring James Dean), the sixties can be described – at least in part – as a period when a series of socially and politically important events failed to attract the attention of the baby-boom generation. In that moment of Causes Without Rebels, even the most atrocious human tragedies left most Quebeckers indifferent. Reading many dusty student periodicals from the sixties, I was struck by the absence of significant student mobilization around hot social issues.

Take for example one of the most media-hyped battles of the time, that of opposition to the Vietnam War. The intensification of bombing in Hanoi did not create a swift and scandalized reaction in the province. According to a poll of Montreal college and university students conducted in 1969 by Marc-André Delisle, twenty-five percent of the city’s student population supported the American intervention in East-Asia, whereas only fourteen percent said they opposed it. The rest, a staggering sixty percent, had absolutely no position on the matter. Even the denunciation of the American invasion of Vietnam was fragile, for it did not go much beyond a stated moral judgment. The fourteen percent of Montreal students who were ready to say “give peace a chance” did not want to be otherwise bothered. “In brief,” concluded the poll’s director, “students are ‘progressive’ or ‘radical’ to the extent that it is ‘useful,’ to the extent that it is ‘in,’ but on the sine quo non condition that it does not get in the way of their petty day-to-day existence.”

The same year, in October 1969, another more amateur poll conducted at the Cegep du Vieux-Montréal concluded that students were interested in very concrete and immediate issues (cine-clubs, sports, loans and bursaries) but that they had increasingly lost interest in issues that were too political and distant (labour strikes, world hunger, etc.). The poll also noted that students were quick to denounce irritating situations but seldom acted on their words. Eighty-three percent of the students polled were fed up with having to eat disgusting sandwiches at the college’s cafeteria and lamented the deplorable state of the college’s library but only seven percent said they would be ready to involve themselves in their student union to remedy the problems. “To the eternal question that asks if the student mass is really lifeless or not,” remarked Robert Chabot, “the research may provide an answer: at the level of verbal manifestations, it is to be noted that everyone expresses opinions that are perfectly relevant…. But at the level of a participative and active project, well then, the results are far more disheartening and unfortunately confirm the common opinion according to which students are generally apathetic.”

I teach at Concordia University and constantly meet students asking me why young people don’t mobilize themselves the way they used to in the sixties. My answer is that the question they’re asking is the same one that students were asking their professors forty years ago. Indeed, what activists decried in 1968 or 1969 was not their comrades’ extremism but their inexcusable passivity. These young idealists couldn’t understand why people were so indifferent to the world’s problems when the world needed them most. They couldn’t conceive that the vast majority of Quebec students, according to Gérald Fortin, defined themselves as “professionals in the making” rather than active citizens and that questions relative to their career took precedence over democratic duties. They realised, wrote M. Gagné-Lavoie, that a minority of committed, courageous, and relatively noisy students served as a screen hiding a vastly conservative and passive student body. Abraham Fox, a student at Sir George William’s University, wrote in February 1969:

Where has the student been all this time? Sure, you hear opinions being expressed on the moving stairs! Sure, you hear “informed opinions” being expressed by the groovy crowd in the cafeteria (you know, between pathetic efforts to flirt and put it on). Sure, everyone is interested and disturbed! Look at it again!!! IT’S JUST A BIG COP OUT. IT IS A WAY OF BEING SOCIAL. IT’S A WAY OF BEING IN THE SET. IT’S ABOUT AS DYNAMIC AS TEATS ON A TOMCAT!! The most disturbing aspect of this whole mess is the fact that almost the whole student body is apathetic.

Trying to fight this general apathy, youth leaders used every opportunity to stir up some polemics in the province. The Vietnam War fit particularly well on their agenda. They attempted to convince fellow Quebeckers that the “criminal and mass destruction methods used by the United-States” were transforming South-Vietnam “into a field of experiment for the United States’ engines of death” and that everyone had a moral duty to react to atrocities that were perpetrated with the consent of the Canadian government. To make sure that Quebeckers understood the gravity of the situation, youth leaders associated the battle raging in Vietnam with the French Canadian fight against exploitation and colonialism in their own province. Both nations were fighting to gain the right to self-government. The Vietnam struggle, therefore, was their struggle.

Despite this aggressive rhetoric, no anti-Vietnam war rallies attracted more than a few hundred participants in the sixties. For example, in October 1968, an international march against the Vietnam War was widely publicized with the distribution of a hundred thousand flyers. The organizers were hoping that five thousand people would come out to Place Jacques-Cartier to voice their support for the cause. Only two hundred militant activists showed up. With the exception of course of the nationalist movement, one must admit that youth rebellion was not the norm in the late sixties. When issues revolved around nationalist questions, people did voice their dissent. There were eight thousand at the McGill Français march in March 1969, and thirty thousand at the Bill 63 march, in October of the same year. But, besides those two events, historians search in vain for mass gatherings in the streets of Montréal, Québec, Chicoutimi or Sherbrooke.

In order to provide a point of comparison, let us remember that the biggest march in the history of the student movement did not happen in 1968 or 1969 but in 2005, when eighty thousand students paraded in the streets of Montreal to protest provincial budget cuts to student aid. The biggest rally in the history of the nationalist movement did not happen in 1968 or 1969 but in 1989, when sixty thousand people braved the cold weather to protest against Bill 178. The biggest event in the history of the Quebec peace movement did not happen in 1968 or 1969 but in 2003, when two hundred thousand people attended a Protest against the Iraq War in Montreal. Everything did not start, and certainly everything did not end, in 1970.

According to the sixties myth, pretty much every baby-boomer was an idealist who longed for peace and justice. This was not so. The proportion of students who committed themselves politically was roughly the same then as it had always been, that is: around five percent. In the United-States, according to a study published by sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset forty years ago, militant activists only represented a small group of college and university students. Karine Hébert came to the same conclusion when researching the Montreal student body in the thirties. I don’t have any precise number to offer but my guess is that one would find at least the same proportion of student activists in colleges and universities today.

This observation is not intended to diminish or denigrate the great accomplishments of the sixties. In emphasizing the long and continuing history of Quebec social movements, the point I want to make is not that the sixties are less worthy of our interest because they were animated by a small group of idealists. Quite the opposite. I tell my Concordia students that the great lesson of the sixties is that a small group of people can accomplish extraordinary things. That you don’t have to wait until you number in the millions to change society. That a seemingly minor collection of committed individuals can have an impact incommensurate to its size. That my students should not be fooled by the sixties myth but should continue to engage themselves – as they most often are – in NGO’s, community work, charity associations, international organizations, social movements, and political groups. During his presidential campaign, Barack Obama liked to repeat that one voice can change a room, and that if one voice can change a room it can change a city, and that if it can change a city it can change a state, and that if it can change s state it can change a nation, and that if it can change a nation it can change the world. Your voice, he told the crowds he was addressing, can change the world. True or not, that to me is the sixties’ fundamental message.

III Power to the People or Power to the Structures

I just remarked that today’s youth are no less active than were Quebec youth in 1969. Yet, it is self-evident that young people were much more active in the sixties than they were in the fifties. If it was always a minority that chanted slogans, marched in the streets, and advocated radical change, what happened in the sixties that made this minority suddenly appear to be more vocal? What changed in Quebec that made it more likely for young people to rebel and protest?

Many people would like us to believe that it was simply a personal realisation that things had to change. It was because people became aware of the world’s problems that they decided they had to do something about it. Watching the news, reading the newspaper, talking to friends, witnessing inequality and injustice, some individuals took it upon themselves to better the world in which they lived. If this reading is correct, then today’s apparently conservative and passive attitude is rooted in people’s unwillingness to do something for others. Quebeckers would prefer their couch potato’s life to a life of adventure and sacrifice simply because they don’t really care. Conversely, if only people realised how much the world needs to be changed, they would willingly commit themselves to this transformation.

In other words, between the sixties and now, the big difference would be that today people don’t believe as strongly in love, sharing, and equality.

My reading of history is different. I think that passivity and revolt are the social products of a specific time and a specific place. People don’t revolt because they suddenly feel like it. A society does not appear more turbulent and politicised because it mysteriously acquires a greater sense of moral outrage. Some social conditions are more (or less) favourable to protest than others.

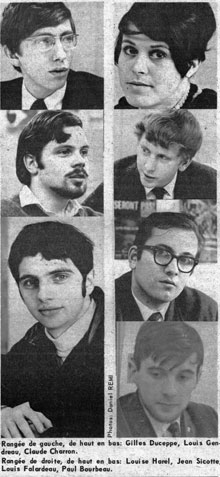

Quebec Student Leaders in 1968: the executive of Union générale des étudiants du Québec (UGEQ). Le Quartier Latin, 15 February, 1969

Compared with the fifties, the sixties certainly exacerbated people’s desire for change. For present purposes, let me take only the situation that prevailed within the education system. I know that by focusing exclusively on the education system I greatly simplify a very complex picture. On the other hand, I believe that the education system provides a very good illustration of the global transformation Quebec society was going through during the Quiet Revolution. In 1968 and 1969, most Quebec activists were students. Some student leaders of that era now occupy prestigious position of power (just think of Gilles Duceppe, Claude Charron, Louise Harel, Jean Doré or Bernard Landry). When they were younger, what was happening in high-schools, colleges, and universities that made them more likely to choose a political career?

First, one has to mention the fact that the baby-boomers represented in 1968 nearly half of the total provincial population. Their demographic weight corresponded to their political weight. Political parties of all affiliations were trying to seduce these new voters by promising them a place in state organisations. Just by being numerically important, Quebec youth benefited from an influence far greater than the one the older generation ever enjoyed.

The baby-boomers were more literate than their parents, and they had acquired their degrees in a time when expertise and technical know-how replaced old French-Canadian wisdom as Quebec society’s dominant ideology. Men and women of science were considered the new ruling class, definitely ousting philosophers and priests. A technological society had to be guided by professionals and experts.

In order to acquire these degrees and certificates needed for professional success (“he who studies grows rich,” declared Premier Jean Lesage), Quebeckers were staying longer and longer in school. The increase in student registration at all academic levels, and in particular at the college and university levels, is nothing short of spectacular. Never before were there so many people sitting on school benches in the history of Quebec.

It is not enough to mention the rise of student enrolment. One also has to note that this growth chiefly favoured the social and human sciences. Half of the growth of universities in the sixties is due to the booming communication, political science, anthropology, sociology, education, and social work departments. The simple fact of studying in a social science department modified the way students looked at society. It is certainly not a coincidence that most sixties activists came from anthropology or political science departments. On the one hand, the work one is asked to do in social sciences involves a strong dose of reformism: medical doctors cure their patients one by one, whereas sociologists pretend at being capable of correcting the problems affecting society at large. By virtue of their profession, sociologists are likely to be do-gooders. On the other hand, social science students normally adhere to a conception of the world where ideas play a dominant role. They define themselves as intellectual workers. Debates late at night over a few bottles of beer continue their daily professional concerns. Endless debates around the correct definition of social classes or the right conception of state intervention are part of the job. More technical sectors, like engineering or chemistry, are less inclined to foster that kind of reflection on ontology or epistemology. This is why people in the human sciences often consider theoretical reflection the noblest activity of a university student, implying by the same token that the ideal figure of a university student, and by extension of all citizens, is that of the critical intellectual.

In brief, and to put my argument in the most simple possible equation, more social science students = more protests. We all know this to be true. The Montreal Polytechnique only once went on strike since its foundation in 1873. Since its creation in 1969, it seems that the Department of sociology at UQAM has gone on strike every year! But there were no social science departments to speak of in Quebec before 1960. And so it is understandable that the sixties witnessed more protest than the fifties.

There was something else. Another point needs to be mentioned to better understand the Quebec youth revolution forty years ago. It is the reform of the education system, flagship of the Quiet Revolution. In particular, the creation of cegeps fostered a context strongly favourable to student mobilization. First, aged 17 to 20, cegep students embodied everything I have already said about the ideal rebel: they were introduced to philosophy and political science without yet embracing a professional career or having family responsibilities. Secondly, it is obvious that the novelty of the cegep experiment constituted a fertile ground for protest. Institutions which had long been established and rested on strong traditions were less shattered than more recent institutions. There were greater waves at UQAM than at Université de Montréal, at the cegep du Vieux-Montréal than at the collège Mont Saint-Louis. The first cegeps opened their doors in 1967 in a certain haste and confusion. The new programs were largely improvised and nourished deep frustrations. Students who would have otherwise never thought of criticising academic authorities voiced their dissatisfaction with the lack of space, the absence of student services, the bureaucratic maze, or the poor quality of the food served at the cafeteria. The ministry of Education had not thought it wise to funnel Quebec youth’s activities into simple pastimes, like sports, photography, or theatre, and therefore, cegep students, parked in immense halls, a little idle, could more easily entertain revolution ideas.

The very architecture of cegeps incarnated an anonymity despicable to those who had been promised a more personalized education. The sixties had announced the dawn of an age of expression and experience. The limited budget of the provincial government and the necessity to proceed without delay to the modernization of an outdated education system had brought Quebec bureaucrats to favour giant auditoriums to intimate class rooms, lectures to seminars, and standardized textbooks to individual approaches. Built like huge cold bureaucratic cement boxes, cegep consecrated such massification of teaching. And as if this was not enough, the vast increase in enrolment led to a devaluation of the diplomas and to an increased competition in the job market. In student papers published at the end of the decade, many articles evoked the fear of unemployment and of a “sacrificed generation,” Ronel Bouchard wrote, in November 1969:

The most stupefying experience that one can try these days is to attend courses. Why? Because it is the place par excellence where false and disincarnated science is taught, that is not a science that teaches how to live and to breath with our guts but a science that we have to learn. This experience is the equivalent of a personal suicide. Unconsciously, a young man or a young girl cut him or herself from the roots that bind him or her to his or her self, to his or her gut, to his or her vital air, to his or her life.

Another student, Danielle Boucher, translated these thoughts in cruder words: “I’m fed up, I don’t want to hear anything anymore. Let them all go to hell.” The education system was not adapting fast enough to the reality of Quebec students. Things had moved too quickly, and in 1969 some catching up was the order of the day.

In due course things quieted down. Social sciences were progressively institutionalized and professionalised. They were divided into sub-specialities (like consumption) and they often adopted a management approach (from time management to class management). Cegeps were organized on a stronger footing. Pedagogy was better adapted to the needs and interests of the baby-boomers. Money was invested in leisurely activities that drove students away from political mobilization.

Montreal University Students March in Protest, 1969. La Presse, 21 October, 1968

This brief description of the education scene in 1969 helps understand why the fifties seem so calm in comparison to the sixties. What the fifties students lacked was not moral judgement but social conditions that could have encouraged them to invade the streets and shout slogans against bourgeois society. The transformation of the education system was of course not the only of these social conditions. Many other factors had come into play. The Quiet Revolution, the rise of an age of affluence, the absence of cultural and political vessels capable of funnelling Quebec youth’s hopes or aspirations are some other obvious other phenomena that proved extremely important. My objective here has not been to provide a detailed account of the broader social context in the province in the sixties but an example of how social conditions may favour (or hinder) political struggles.

The last aspect of the sixties myth emphasizes people’s willingness to dissent. If only people would open their eyes, so the myth goes, the world would be a better place. If only, to use Lennon’s lyric, they could “imagine all the people sharing all the world.” Unfortunately this is not how society functions. Most often, people rebel at a certain time because the social context makes them likely to do so. The decolonization of third-world countries, the Civil Rights Movement, the North American Indian awakening, the Quiet Revolution, the Youth Revolt, the Second Wave of Feminism – all of these events happened at pretty much the same time because they were driven by the same forces of modernization. It was not just lucky timing.

I know many friends who find such a sociological reading of history depressing. Personally, I don’t think that such a sociological interpretation should deter political activism. I don’t, because I believe that many factors that existed forty years ago are still active today. Means of communications have multiplied, social science departments have continued to grow, countries’ interconnectedness is greater now than ever before. The very social conditions that made the sixties so turbulent have not gone away. Just looking at some college and university students’ endeavours makes anyone realize how much Quebec youth is still active in trying to change the world. There does not seem to be a sphere of social activity in which they forget to get involved! World poverty, slow food, heart disease, aboriginal rights, immigration, multiculturalism, organic food, children’s rights, urbanism, alternative media, police brutality, racism, labour rights, and so on and so forth. The list of their interests and commitments is endless.

To foster political awareness, young people today now use a plurality of tactics. In particular, the internet represents a fantastic tool for mobilization, allowing for ‘virtual sit-ins’ and other online direct actions. For example, an Amnesty International campaign was recently launched called “Get in Bed for Darfur,” which “draws on the energy, hope and call to action of the original bed-in, and urges us to help bring peace in 2007 to the people of Darfur.” (See www.amnesty.ca/instantkarma/bedins/faq.php#b1.) Everyone can now organize a bed-in in their private bedroom. Whether these modes of action are more or less efficient than the sixties occupations of actual buildings remain to be seen. But one cannot say that they cannot facilitate mass participation.

IV Conclusion

I have described how the sixties counterculture was not as corrosive of the status quo as the sixties rebels pretended. It easily meshed into the consumer society’s social fabric. While influencing Quebec society to open up to diversity and recognize people’s personal quests, it never developed into a radically different social order. This being said, its impact remains largely positive.

I have also described how sixties activists consisted mainly of a handful of dedicated intellectuals and militants. The nationalist movement notwithstanding, only a minority of Quebec youth were actually involved in political organizations. But their marginality was incommensurable with their capacity to change society. If there is a lesson to gain from studying the sixties, it certainly is that a few empowered individuals can do extraordinary things.

Finally, I have tried to show that a series of events led to the social awakening witnessed in the sixties. In comparison with the fifties, the sixties corresponded to a period of greater youth rebellion. This evolution can be explained by looking at the social conditions in which the baby-boomers grew up.

Naturally, at the end of such a sociological analysis, the question arises: what has changed in the last four decades? I have emphasised the profound continuity that exists between the past and the present and have tried to show that the sixties counterculture is alive and well, that between 1969 and 2009 the number of activists is roughly the same, and that the emerging social conditions of the sixties still prevail to some extent today.

So is there anything really different? Are we really – so to speak – breathing the same air?

Not quite. Although the members of Generation X are heirs to the sixties and, as a result, benefit from the social advancements that their predecessors fought for, many things have changed when it comes to political participation. Let me state only two major changes.

Poster for The Celebration (1962). Photograph by Michel Lambeth. National Gallery of Canada. ©The Estate of Greg Curnoe

First, most people remember the sixties as a time when ordinary people demanded peace in the world. Maybe some of you know the Beau Dommage’s song: En 67 tout était beau. J’avais des fleurs dans les cheveux, fallait-tu être niaiseux. But civil disobedience and peaceful rallies were part of a philosophy that belonged to an earlier period of political protest. If the sixties started with the Civil Rights Movement and the SDS they ended with the Black Panthers and the Weathermen. In Quebec there was also an evolution from a Quiet Revolution to a pretty Stormy Revolution. Graffiti, bombings, burning cars, vandalized schools, police brutality, intimidation, illegal building occupations, and death thyreats were all part of the 1967-1970 period. The FLQ’s actions were condoned by many Quebeckers who believed that only through a military upheaval would independence and socialism ever come about. Before the Opération McGill français, a march organized in March 28th, 1969, to demand the transformation of McGill University into a completely French institution, some young Turks expressed their will to literally burn McGill to the ground. The FLP turned into a “machine à manifs,” using every opportunity to launch brutal attacks against the bourgeoisie.

This violence seldom went beyond incendiary declarations. The situation in Italy, Germany, France, Japan, or the United-States was always incomparably more serious than in Quebec. And yet there is something troubling in reading old issues of student papers in which violence is trivialized. This fascination with violent actions is certainly something that we don’t hear of as often anymore.

The other big difference between now and the sixties is that Quebec youth does not believe as much in realizing a common front against all oppressors. It has lost the naive belief that there was the bourgeoisie in one corner and everybody else packed in the other corner. In the sixties things seemed – in a way – more simple. Women, ethnic minorities, First nations, French Canadians, third-world countries, youth, peasants, workers and all other oppressed groups were seemingly united in a common cause. They all (apparently) participated in the same struggle.

Today we realize that the situation is far more complex. The interests of Quebec youth (to be granted free education, for example) do not necessarily fit with the interests of those who want a greater portion of the government’s budget to be allocated to helping countries fight famine. Human rights may not always be in line with aboriginal rights. The need to provide jobs to workers may not always help to preserve the environment. We have come to accept that we live in a divided world and that the quest for the common good is not as straightforward as some sixties intellectuals liked to assume. This fight for justice is long and sinuous.

This is something that we now know and have to live with. But is it any reason to stop dreaming? Following their predecessors’ footsteps, most Quebeckers who are now in their thirties and forties readily accept the sixties message of hope: “It’s only a beginning. Let us continue the struggle.”

SOURCES

Anonyme, “10 p.c. des étudiants du Québec ont fait l’Expérience de la “mari” et de ses dérivés”, Le Devoir (24 septembre 1968), 11.

Anonyme, “Parallèle entre la lutte du peuple vietnamien et celle du peuple du Québec”, Le Devoir (18 octobre, 1967), 9.

L’Antenn [journal du Cégep Édouard-Montpetit], (No 4, 8 novembre 1968, cité par Élizabeth Bielinski, “L’idéologie des contestataires” [septembre 1969], dans L’étudiant québécois. Défis et dilemmes. Rapports de recherches, (Québec, L’Éditeur Officiel du Québec, 1972), p.323.

Ronal Bouchard, “Asphyxie,” Animation (c. novembre, 1960), 10.

Daniel Boucher, “Je ne rentre pas parce que …,” Le Quartier Latin (17 septembre, 1969), 35.

Robert Chabot, “La montée contestataire,” Artur, Vol. 1, no. 2 (30 octobre, 1969), 3.

Claude Charron, “Que sont devenus les leaders d’octobre 68?”, Le Quarter Latin, vol. 1, no. 1 (septembre 1969), 17.

Marc-André Delisle, “Les étudiants ne sont-ils que des révolutionnaires de taverne?” in Jean de Montigny and Pierre Robert, Enquête sociologique sur le comportement étudiant (region de Montréal), vol. 3 (Summer 1971), 5.

Gérald Fortin, “Le paradoxe de la démocratisation”, Le Carabin, special issue (septembre 1966), 8.

Abraham S. Fox, “Where have all the students gone?”, The Georgian (6 February 1969), 3.

M. Gagné-Lavoie, “Open Letter,” Le Quartier Latin (1 Decembre, 1966).

Karine Hébert, Impatient d’être soi-même. Les étudiants montréalais, 1895-1960 (Montreal: Presses de l’Université du Québec, 2008).

http://www.amnesty.ca/instantkarma/bedins/faq.php#b1

Seymour Martin Lipset, “Students and Politics in Comparative Perspective”, in Seymour Martin Lipset and Philip G. Altbach, Students in Revolt (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1969), xviii.

Pierre Paiement, “Etre dans sap eau,” Le Quartier Latin (15 Octobre, 1969), 25.

Marc André Poissant, Paul Desormaux, étudiant (Montréal, Éditions Québécor, 1978).

François Ricard, La génération lyrique. Essai sur la vie et l’oeuvre des premiers-nés du baby-boom (Montréal: Boréal, 1992), 90-91.

Réal Valiquette, “Que sont sevenus les leaders d’octobre 68?” Le Quartier Latin, vol. 1, no. 1 (septembre 1969), 19.

Joan Wallach, “Chapter Programming,” SDS National Council Meeting Working Paper, 1963, p.1, cited in Frédéric Robert, La Nouvelle gauche américaine: faits et analyses (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2001), 136. Wallach: “When you ask where SDS is going, if you mean ‘what’s the outline for the future society?’ our answer is ‘we don’t have one.’ This is a virtue rather than a failing of SDS. In the course of action, the real action taken by SDS members, the answers will come. The future will emerge in the course of action.”

Jean-Philippe Warren, Une douce anarchie (Montréal: Boréal, 2008).