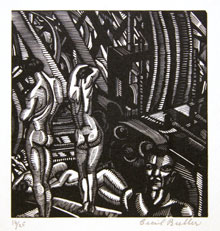

Cecil Buller “Man–Machines” (1924), wood engraving on wove Japan paper, Carleton University Art Gallery, Gift of Dr. Sean Murphy, 2007.

IN THE LATE 1960S, during the flowering of New Left political activism in Canada, conventional wisdom had it that there were very few true English–Canadian intellectuals. For that matter, there were few British intellectuals either. The British political tradition, which Canada had inherited, and a subset of which it continued, was essentially pragmatic and commonsensical. Public affairs were about interests, not ideas, and always had been. Real intellectuals were European, and especially French. Jean–Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir were intellectuals, as were Max Weber, Antonio Gramsci, and Georg Lukacs. The United States also had intellectuals – C. Wright Mills and Noam Chomsky, for example – but the foremost American intellectuals were actually European refugees and emigrés, such as Hannah Arendt, Erich Fromm, and Herbert Marcuse. In my own understanding, the species ‘intellectual’ had originated in nineteenth–century Russia, where Alexander Herzen, Vissarion Belinski, Nikolai Chernyshevsky and other members of the pre–revolutionary intelligentsia had been the first ‘intellectuals.’ In other words, to be an intellectual was not only to be a thinker, it was also to be a critic and a dissenter.

Frank Underhill, who was then in his seventies, had long held much the same opinion, with the difference that his points of comparison were England and the United States, rather than continental Europe. He was not ignorant of other intellectual traditions – far from it – but his own thought had been influenced by English and American writers more than any other, particularly the ‘new liberals,’ socialists, and progressives of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and he was dismayed by the apparent absence of any equivalent in Canada, and by the consequent (as he believed) underdevelopment of Canadian intellectual life in general. As a high school student in Markham, Ontario and a university student, first at Toronto and then at Oxford, before the First World War, he had come to regard English thought – from Hobbes and Locke to Edmund Burke, Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill, Leslie Stephen, John Morley, George Bernard Shaw, and L.T. Hobhouse – as infinitely superior to anything in Canada, past or present. He believed that Canadian public life would advance beyond the grubby parochial concerns of getting and spending only when the seeds of an intellectual tradition had been planted and borne fruit.

These two views of intellectuals in Canada – Underhill’s and that of the sixties left – were at once alike and opposed. They were alike in thinking that intellectuals were to be found somewhere else, and that a primary index of the backwardness of their own milieu was the absence of a type that marked a culture’s intellectual maturity. The British historian Stephan Collini argues (in his highly informative Absent Minds: Intellectuals in Britain) that this belief characterized intellectuals everywhere; indeed, that it was among the defining characteristics of ‘the intellectual.’ Another culture’s vibrant intellectual tradition was a judgement on the feebleness of one’s own. The two views, however, were also opposed, in that the sixties left did not regard Underhill as an intellectual model or even as much of an intellectual at all, while Underhill then saw himself, as he had throughout most of his adult life, not merely as an intellectual, but as a lonely exemplar of the type, struggling to establish its legitimacy in the inhospitable conditions and circumstances of Canadian society and culture. I would like to explore the kinship and polarity of these two views in this essay, and particularly to trace Underhill’s understanding of ‘the intellectual’ as a cultural figure and the ways in which it was, for him, not just a tool for the analysis of Canadian politics and society, but a badge of his own individual identity.

II

.jpg)

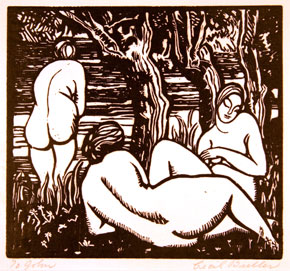

Cecil Buller “Skyscrapers” (from the “Song of Solomon”) (1929), wood engraving on wove Japan paper, Carleton University Art Gallery, Gift of Dr. Sean Murphy, 2007.

After returning from Oxford to begin a career as a professional historian, and more particularly after returning from service in the First World War, Underhill sought to uncover the primitive beginnings of a Canadian intellectual tradition; its pre–figurement, so to speak. He found them in George Brown’s Toronto Globe just before Confederation, in the Canada First movement just after, in the expatriate English historian and journalist Goldwin Smith at the end of the nineteenth century, and in the nationalists J.S. Ewart and Henri Bourassa at the beginning of the twentieth. He also spent much time and energy trying to needle, prod, berate, and shame his peers in Canadian academic life to engage critically in public debate, in a manner similar to that of A.D. Lindsay (one of his Oxford tutors) and R.H. Tawney in Great Britain, or John Dewey and Charles Beard in the United States, and in this way to found a living Canadian tradition.

The “real weakness” of radicalism in Canada, he wrote in 1929, was a “lack of intellectual leadership,” the result, at least in part, of the propensity of university professors to worship “at the shrine of the god of respectability.” He thought this was possibly due to their social insecurity – a by–product, in turn, of paltry remuneration – but his opinion was unchanged thirty years later. Looking back on his career as a controversialist in 1961, he proudly acknowledged that he had never achieved “that austere personal objectivity” exemplified by most of his academic colleagues, “who lived blameless intellectual lives, cultivated the golden mean, and never stuck their necks out.” He had no regrets.

By the time he wrote this, however, he had actually made a partial peace with grubby day–to–day politics; at least, he had come to think that William Lyon Mackenzie King, one of its most successful practitioners, maybe had something to offer, after all, and that the socialist movement which he himself had supported since the early 1930s had perhaps outlived its usefulness. While he had not taken part in the founding of the Co–operative Commonwealth Federation in 1932, he had drafted its founding platform document, the Regina Manifesto, the following year. Under his leadership, the League for Social Reconstruction, which he had helped to found in 1932, had become closely allied with the CCF, its ‘brainstrust,’ in the lingo of the time. In the forties and fifties he had grown away from the CCF, partly because he discovered that, once institutionalized, its leadership was no more tolerant of dissenting opinion than any other establishment, partly because he thought that German Nazism and Russian Communism had shown the dangers inherent in a too–powerful state, and partly because he had concluded that Keynesian economics and the Roosevelt New Deal offered a more liberal means of restraining capitalist greed in the public interest. In foreign affairs, events – the Second World War – had forced him to recant his isolationism of the 1930s, and to acknowledge Mackenzie King’s skill in maintaining national unity in the face of war–time strains, and, more generally, in advancing the cause of national autonomy. By the late fifties Underhill was more a Liberal than a CCFer.

This did not mean that he had given up his independence, but it seriously damaged his reputation along leftists, both ‘new’ (of my day) and old (of his), to whom he appeared a sell–out, or, at best, an example of the very thing he had spent his life opposing: a compromiser and an opportunist. His appointment in 1955 as curator and honorary writer–in–residence at Laurier House in Ottawa, a shrine of Canadian Liberalism, only gave his critics further ammunition. At around the same time, his defence of the United States in the Cold War sealed the case against him, even though his position was consistent with the one he had taken twenty years before – against the British Empire and in favour of Canada’s essentially North American character – when it had defined his radicalism and almost cost him his professorship at the University of Toronto. He thought that, in the Cold War, one simply had to choose between the USSR and the US, and that, under the circumstances, there was actually no choice. He also found himself courted by the mainstream media for commentary on all manner of public questions, which marked his ‘apotheosis’ as a critic, as his biographer, Douglas Francis, notes, but which was also the kiss of death to those for whom the mainstream was precisely the problem. Instead of being seen as the maker of an intellectual tradition, Underhill was widely regarded as yet more evidence of its weakness.

Ironically, two conservatives, the philosopher George Grant and the historian Donald Creighton (generationally Underhill’s juniors and the latter a long–time colleague and rival), were embraced on the intellectual left, primarily because of their anti–American nationalism, but also because they represented an idea that gained wide currency in the sixties, that there was historically in Canada a peculiar affinity between toryism and socialism. Underhill was baffled by this. To someone of his small–‘l’ liberal origins, he said on the occasion of his eightieth birthday in 1969, it was “unthinkable ... that radicals of the left should ever dream of combining with radicals of the right to liquidate what they call the liberal establishment.” Nothing more sharply alienated him from the contemporary left. His friend Norman Ward, the University of Saskatchewan political scientist, was sympathetic to his “anti–anti–Americanism,” but gently suggested that the anti–Americanism of Canadian youth in their day might actually be serving “the same liberal ends” as Underhill’s anti–British views had once served in his.

In any event, Underhill and the left were at odds in the 1960s, which helps to explain why he and the forerunners of liberalism that he brought to light in his historical studies had so little intellectual legitimacy in left–wing circles at the time. His liberalism alone, of course, partisan apostasy aside, was enough to make him suspect. Radicals of the sixties, myself included, sought a more fundamental basis of dissent and more systematic sources of society’s ills than liberalism could possibly offer of liberal capitalist democracy. Their search grew partly from the resurgence of Marxism, which rendered anything short of radical change a compromise with things as they were, whereas Underhill was by any standard a reformist. Even as an architect of CCF policy he had been, in Marxist terms, a bourgeois socialist, arguing for changes that, in the long run, would sustain capitalism rather than overthrow it. Pursuit of fundamental change also grew out of a cluster of other radical and ‘counter–cultural’ movements whose concerns Underhill’s essentially political world view did not begin to address: feminism, environmentalism, anti–imperialism, agricultural transformation, free schools. As against the all–encompassing, often theoretical, sometimes utopian tendencies of such programs, Underhill’s liberalism was hopelessly piecemeal, empirical, pragmatic, and utilitarian.

Cecil Buller “Summer Afternoon” (1915), linocut on laid paper, Carleton University Art Gallery, Gift of Dr. Sean Murphy, 2007.

His idea of ‘the intellectual’ crystallized in the 1930s, when he was himself the target of criticism from various quarters – from politicians, businessmen, newspapers, and colleagues – and he defended himself accordingly. The British intellectual tradition was not only one he admired, but it could be turned against his critics, who did not seem to have this aspect of British culture in mind when they demanded he show suitable respect for the mother country. Academics might also take note: Oxford, Cambridge, and London were schools of statesmanship rather than “the breeding grounds of Ph.D.s” that Canadian universities were in danger of becoming. He pointed out that the example of “the academic man” participating in public affairs had precedents in Canada – in Principal George Grant of Queen’s University, D.B. Weldon of Dalhousie, and Stephen Leacock of McGill – which he also turned to account. Was his own problem, perhaps, not that he was participating at all, but that he was participating as a radical? Intolerance of intellectuals only showed that Canada had not yet emerged from its frontier stage of development.

In calmer retrospect (though still making a point – he was speaking to a group of Liberals) he later claimed that J.S. Woodsworth had played a major role in advancing the process of maturation when he had invited intellectuals to take part in CCF policy–making. Woodsworth had also encouraged “intellectuals” to organize themselves (his quotation marks, an indication of the infancy of the term) and the creation of the League for Social Reconstruction, modelled on the Fabian Society in England, had been the result.

Underhill continued to think of intellectuals in oppositionist terms even when it seemed that he had relaxed his standards. Speaking to a hall full of academics at Queen’s in 1967, he began in a characteristically disarming manner by warning against misleadingly precise social scientific models: “It is sufficient to say at the outset [that] I think that intellectuals generally are people like you and me.” Yet, he was seldom as innocent as he appeared. Despite a necessary imprecision, it was still possible to trace the way the term was actually used and thus to situate its meaning historically. He had found that the word ‘intellectual’ had first been used as a noun to describe those who supported Alfred Dreyfus, the French Jewish army officer who had been charged with espionage, convicted, and then exonerated at the turn of the twentieth century. Ever since, ‘intellectuals’ had been distinguished by their willingness to ask “inconvenient and embarrassing questions about the implications of accepted beliefs or policies,” and to ask them “at inconvenient times and in embarrassing ways.”

At other times they, or individuals very like them, had acted differently. From 1867 to 1918, ‘intellectuals’ such as W.A. Foster of Canada First, Edward Blake, Stephen Leacock, and Andrew Macphail, the McGill professor of medicine and editor of University Magazine, acted “merely as a clerisy, expounding the meaning of our communal experience as they saw it.” After the First World War there was a perceptible “change of temper.” Intellectuals became anti–establishment critics, Mackenzie King (if only briefly) and Woodsworth among them. Now (in 1967), it seemed that intellectuals were everywhere, yet Underhill found himself still dissatisfied, for reasons perhaps implicit in the reading he recommended to his audience at Queen’s: Lewis Coser’s Men of Ideas, Richard Hofstadter’s Anti–intellectualism in American Life, and an essay by H. Stuart Hughes, “Is the Intellectual Obsolete?”

All three authors were concerned for the fate of intellectuals in contemporary society. Underhill lingered on Hughes and the distinction he drew between “genuine intellectuals” and “mental technicians.” The latter were specialists and experts, while the former were generalists whose thought and action ranged far beyond their particular field of expertise. Just what and who were intellectuals thus varied depending on context, circumstances, and their conception of themselves. Underhill’s own use of the term illustrated its variability, though no one in his audience at Queen’s can have thought by the end of his talk that he seriously meant to include all of them in his definition of ‘the intellectual.’

III

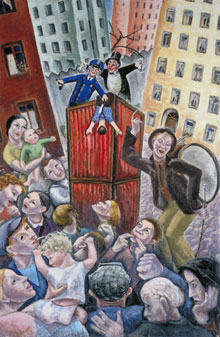

Paraskeva Clark. “Petroushka” (1937), oil on canvas, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Reproduced Courtesy of Clive and Benedict Clark.

No question more consistently engaged Underhill’s attention than the role of intellectuals in Canadian public life. Even in his later years, when he thought they were growing more numerous, he remained doubtful of their status and security. Shortly after the release of the Report of the Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences – the Massey Report – in June 1951, he commented scathingly that it was “already being brushed aside by the ‘practical men’ as the work of long–haired high–brows. There is no country in the world where intellectuals suffer from such low repute as in Canada.” He offered a slightly more temperate and rounded version of the same judgement fifteen years later in the introduction he wrote to the Carleton Library edition of André Siegfried’s early twentieth–century study of Canadian politics, The Race Question in Canada. Siegfried was a French sociologist and geographer, the “Tocqueville of Canada,” Underhill called him. Canadians’ long neglect of him reflected poorly on themselves, he thought, especially in comparison with Americans, who had never stopped talking about his countryman’s classic study of American democracy since its first publication in 1835. “We have shown little taste,” he alleged, “for that realistic and critical self–knowledge which is the mark of maturity.”

Underhill had first read Siegfried in the English translation published in 1907 (more for an English audience, he noted, than a Canadian one), a year after the original French edition. He had found it on sale at Blackwell’s book shop in Oxford during his student days there from 1911 to 1914. Since then, he had followed all of Siegfried’s work, including his books on France (based on lectures he heard Siegfried deliver at the Williamstown summer institute, at Williams College, Massachusetts, in 1929) and the United States, and a second book about Canada, published in 1937 and re–issued ten years later in a new edition. The fact that Siegfried had continued to be interested in Canada, and to write about it, yet had remained almost unknown to Canadians, only confirmed Underhill’s low estimation of his fellow citizens’ intellectual maturity.

The Race Question in Canada, though dated in its particulars, addressed permanent features of Canadian public life and was especially pertinent in the 1960s, he thought, because of its insights into the relations of French– and English–speaking Canada. It was just the kind of book, in fact, that Canadians needed to read. Siegfried was a modernist and a secularist in his belief in the separation of church and state, the result of having lived as a Protestant in Catholic France, which meant that his analysis of the nineteenth–century semi–theocratic Quebec state was attuned to the sensibilities of the Quiet Revolution. He was a realist, which meant that he was unsparing in his depiction of the play of material interests in political conflict, though over time he came to see – rather like Underhill himself – that the Anglo–Saxon pursuit of “material prosperity for everyone” had an element of its own moral idealism. And he was so “impartially unflattering to all parties” that no one could turn his conclusions to partisan ends.

Underhill’s belief in the intellectual immaturity of Canadians and their need for guidance, instruction, and stimulation, especially as compared to the English and the Americans, took root at an early stage of his life. Between the resources of his Stouffville home and those of the local public library, he had taken in the vibrancy of American literary culture before the First World War, both its lively periodical literature (McClure’s, Collier’s, and Harper’s Weekly, among other magazines) and the exhilarating exposés by muckrakers like Ida Tarbell, Lincoln Steffens, and Upton Sinclair. There was really no Canadian equivalent.

He had spent three years in the intellectual centre (Balliol College) of the cultural capital (Oxford University) of the greatest empire the world had ever known and been impressed by all it had to offer: clubs such as the Fabian Society (which was socialist) and the Russell and Palmerston Club (which was liberal), speeches and lectures by men ranging from the eminent legal scholar A.V. Dicey to the Labour Party leader Ramsay MacDonald, journals such as the Nation and the Manchester Guardian, plays by G.B. Shaw, and novels by H.G. Wells. Leading academics entered into public controversy, which Underhill believed, even at the end of his life, gave an intellectual vitality to British political parties missing from their Canadian counterparts. England was the very essence of ‘maturity,’ whatever one might think of its empire or its social system.

The role of intellectuals in such a mature liberal democracy was to educate the citizenry, raise them up intellectually and morally, and so stimulate them to participate in public life in aid of their further advancement. “The truest democracy,” he wrote in a senior undergraduate essay on Hobbes and Burke in 1911, “aims ... not at levelling down to the lowest but at levelling up to the highest; its essential demand is not that the prescriptive privileges of the classes be abolished but that they be shared among all.” This was the ideal of all liberal democrats in the nineteenth century, and it continued to motivate Underhill and many others through most of the twentieth.

It found clearest expression, appropriately enough, in his various pronouncements on the means and ends of university education. He told an audience at the University of Alberta in 1924 that the “man on the street” yearned for guidance, but universities, at least in North America, failed to respond. Professors and students were too much in thrall to the gods of either science or “general education.” Science had achieved many triumphs, but world war was among them, and a repetition of its horrors would only be prevented by the creative study of politics, which was suffering increasing neglect, while the organization of the humanities into “courses” on the model of the sciences, which students could “elect” or not, resulted in ignorance and superficiality. He recommended instead a coherent program of study like the “honour school of Modern Greats” at Oxford to turn “our American universities” [sic] into schools of citizenship and statesmanship.

Here and elsewhere, Underhill came very close to implying that all intellectuals were professors, yet clearly not all professors were intellectuals. Science professors, he thought, tended either to disdain the mundane world of politics or to regard its complexities as reducible to simple formulas. Far worse – scientists, after all, were among the pioneers of the modern age – were professors of commerce and finance, who taught the purely practical skills of commercial enterprise and sought to ingratiate themselves with businessmen in order to ensure that their students would find jobs after graduation. “One would no more look for an economic heretic coming out of their halls than one would look for religious heretics among the graduates of Jesuit schools,” he said in another talk a few years later. “Yet the future of business, as of every other form of human activity, depends upon its heretics.” Even those who taught in the humanities and social sciences were not necessarily intellectuals by virtue of their field alone, since many subscribed to the ideal of the “research hero” alone in his study, abstracting “forces” and “laws” of human behaviour in imitation of his scientific brethren. The lure of the research model was especially powerful in North America, and Underhill’s resistance to it was an indicator of his continuing cultural attachments to Britain.

Already in the twenties, then, Underhill had arrived at a rough version of the distinction he found so appealing in Stuart Hughes a half–century later, between “genuine intellectuals” and “mental technicians.” The measure of genuineness lay partly in one’s interests and areas of knowledge – the most likely candidates were to be found in the humanities – and partly in the posture one adopted in one’s public engagements, hinted at in his allusion to the necessity of heretics in modern society. Heresy entailed public criticism and dissent, the essential function of intellectuals; it also implied that only those who paid for their dissent in some way, or risked doing so (at the cost at least of their respectability, if short of actually burning at the stake), were truly intellectuals. Conflict with authority, whether political, institutional, or social, was thus a test of an intellectual’s credentials.

This was a view of ‘the intellectual’ consonant with, and partly rooted in, the individualism of John Stuart Mill, which Underhill had first encountered in a serious way as a student at the University of Toronto. Mill was then not yet the mythic figure, virtually synonymous with liberalism, that he was later to become, and his legacy was subject to dispute. Underhill attempted an assessment of it in an essay that won him the University College English Department’s Frederick Wyld Prize in his graduating year. In On Liberty, he wrote, which was “generally acknowledged to be his best and most finished production,” Mill argued that freedom of thought was necessary to the preservation of “a strong and energetic society.” Since “the masses” were prone to thinking of their own “genius or energy” as the maximum possible or desirable, dissent – or heresy – was necessary if modern democracy was to rise above collective mediocrity.

The heretic, of course, was as much a heroic figure as any researcher, though in fairness to Underhill it should be noted that he summoned no one to worship at the altar of the intellectual; he was too much the agnostic, even within his own belief system, to counsel submission to any god. Subject to sceptical inquiry, however, the intellectual was to be followed in the guidance he offered. At the same time, Underhill was far from optimistic, even early in his career, that this would occur, and he remained doubtful thereafter. While he told his University of Alberta audience that the “man in the street” was hungry for instruction, this was more the expression of an ideal than an empirical observation, and a rhetorical device that enabled him to criticize academic quiescence. The question he asked a few moments later – “Is there not something pathetic in the simple minded credulity with which our western voters will swallow ever changing panacea [sic] for their ills which are offered them by their leaders?” – reflected the misgivings about the obstacles to popular enlightenment that leavened his optimism. Formal education, then, would not render the intellectual obsolete by making everyone an intellectual; rather, it would produce a cadre of men and women capable of recognizing independent thought and individual genius when they saw them, of tolerating heretics, and of rationally assessing the guidance they offered.

IV

Cecil Buller “French Canadian Oven” (1919), linocut on laid Japan paper, Carleton University Art Gallery, Gift of Dr. Sean Murphy, 2007.

Underhill’s scepticism of “the masses” showed itself not only in his reading of Mill and Mill’s concern to prevent democracy from turning into popular despotism. It was evident also in his admiration of G.B. Shaw’s defiance of convention and irrepressible instinct for controversy. It showed itself in his taste for the corrosive satire of H.L. Mencken, from whom he borrowed the witticism, “the booboisie” – though the popular American humourist was equally contemptuous of the vox populi, as Underhill (and his readers) well knew. It showed itself, above all, in the eagerness with which he devoured everything written by the American journalist Walter Lippmann, starting at least as early as Lippmann’s seminal post–war essays on public opinion.

Lippmann (who was, coincidentally, born in 1889 and thus an exact contemporary of Underhill’s) came away from his involvement in censorship and propaganda with the American government during the First World War, and from his earlier reading of Sigmund Freud, suspicious of the public’s capacity for rational judgement and convinced of its vulnerability to manipulation by the clever deployment of images, myths, and symbols. In the conditions of complex modern industrial societies, people were cut off from direct engagement with their environment; instead, they were caught in a web of perceptions communicated by advertising and the news. It was the responsibility of the rational elite – experts, in Lippmann’s lexicon – to penetrate beneath appearances and advise decision–makers as to their best course of action.

Underhill, somewhat in spite of himself, found Lippmann very persuasive. The Phantom Public (1925) was “anti–democratic,” he told a correspondent in 1926, but its author was “the most suggestive writer on public affairs in America today.” Underhill knew that business and government sought to manage public opinion – to “manufacture consent,” in the phrase coined by Lippmann and made current in modern times by Noam Chomsky – by propagating a national interest or ideology. Economists, he notoriously said, contributed to sustaining the legitimacy of the national ideology by serving as the “intellectual garage mechanics of Canadian capitalism,” tinkering with the timing here or the brake linings there, and advising on major repairs through their participation on royal commissions. His additional comment, that historians acted as the front–office salesmen, providing a glossy cover story of progressively evolving self–government and national autonomy, achieved less notoriety.

Even as he saw the conservative uses to which Lippmann’s analysis could be put, however, he acknowledged its force. Society and government had become highly complicated, perhaps too much so for the average person to comprehend, requiring specialists to lift the veil of perceptions, interpret complex procedures and operations, and even control them. The same was required of intellectuals; hence, Underhill was always demanding demystification and “realism” in social and political analysis, and, at times, ‘the intellectual’ as dissident shaded into the intellectual as expert or as educated person in his usage – the intellectual, that is, as university professor, plain and simple.

Lippmann’s analysis was similar to – indeed, was partly based on – the psychological studies of the early (though subsequently lapsed) Fabian socialist, Graham Wallas. Prompted in part by popular reaction in England to the Boer War at the turn of the century, Wallas looked to social psychology for an explanation of why people acting in the mass so evidently failed to conform to eighteenth–century Enlightenment ideals of rational humanity. In Human Nature in Politics (1908), he argued that people arrived at their political opinions, not by rational inference, as many idealistic liberals believed, but by “unconscious or half–conscious inferences fixed by habit.” By no means cynical, any more than Lippmann was, Wallas believed that with improved education, better electoral practices (such as closing public houses on election day), and “enlightened direction from above,” working class voters could be led to make informed choices at the ballot box. In a later book, The Great Society (1914), he emphasized that, in the alienating conditions of advanced industrialization, progress would not just happen, nor would it arise from some transcendent collective will; individual human beings had to make it happen by means of mundane, practical actions. Underhill read both books in the early months of 1915 and was later to recall that, together, Wallas and Lippmann had had the courage to confront the “non–rational, darker sides of man” and to ask difficult questions about the adequacy of liberal democratic ideology in the “post–1914 world.”

It is tempting to speculate that Underhill’s Presbyterian upbringing predisposed him to a sceptical view of flawed human nature, and hence to an acceptance of Wallas’s and Lippmann’s arguments, just as Peter Clarke has speculated, in his book Liberals and Democrats, that Wallas and other Fabians carried forward the earnestness of their early religious faith to their later secular commitments. Underhill abandoned his own Christian belief as a young man, under the influence especially of Leslie Stephens’s An Agnostic’s Apology and Other Essays, though apparently without experiencing the kind of family tensions that often accompanied such renunciations of faith (in Wallas’s case, for example). Newly arrived in Saskatoon in 1914, he complained freely to his devout mother back home in Toronto of the boredom of Sundays in a city of church–goers, and later, during the war, he sent his younger sister Isa a copy of Shaw’s Androcles and the Lion, recommending in particular its prefatory humanist commentary on the history of Christianity. He often described intellectuals as modernists doing battle with dogma and fundamentalism, even when the fundamentalists in question were literalist adherents of the Regina Manifesto, rather than religious believers, strictly speaking. In their educational role, intellectuals were a kind of secular clergy, ministering to the moral and intellectual needs of their electoral flock.

The elitism implied in this conception of intellectuals intensified over time, as the concepts of ‘mass society’ and ‘mass culture’ came to be more widely used to describe modern life. Underhill recommended Hofstadter’s Anti–intellectualism in American Life to his listeners at Queen’s in 1967 because it showed how the people whose interests intellectuals thought they were defending often turned out to be the most serious threat to their freedom of speech. On another occasion, he used Robert Bolt’s popular play of the 1960s about the martyrdom of Sir Thomas More, A Man for All Seasons, to make the same point. Bolt’s figure of the Common Man served as More’s executioner, advising the audience that, “It isn’t difficult to keep alive. Just don’t make trouble.” University professors, wrote Underhill, were “up against the Common Man,” demanding that he rise above himself by cultivating his intellect and imagination. Professors were an elite in a society that needed elites but resented them as undemocratic, whereas, on the contrary, the intellectual elite were “necessary to make democracy work under modern conditions.” The irony of the class system in Britain, he added (showing once again his divided cultural attachments), was that old habits of deference insulated British democracy against the populist eruptions endemic in North American mass society.

To declare oneself an intellectual in the circumstances of mass society, then, was both to assert one’s leadership role and to affirm its value. Both were grounded in an older model of deliberative democracy, in which public decisions were thought to be the product of rational discourse among participating citizens who, in the process of participation, educated themselves and others through various media of communication. Now, in modern society, rational opinion formation was threatened by experts who, though seemingly independent, were really the spokesmen for special interests, and by public relations men whose rise had paralleled the emergence of a new understanding of how opinion could be manipulated. It was also threatened by the vulnerability of ‘the public’ itself – if it still existed – to manipulation, with the result that the tension between opinion–leading and opinion–following, always present in public debate, was heightened. If the thought and action of ‘the mass’ were more governed by mass psychology than by informed reason, what confidence could one have that it would be receptive to one’s rational leadership, or that it would even recognize rational argument when presented with it?

V

.jpg)

Cecil Buller “Kneeling” (from the “Song of Solomon”) (1929), wood engraving on wove Japan paper, Carleton University Art Gallery, Gift of Dr. Sean Murphy, 2007.

By the standard of most modern definitions of ‘the intellectual,’ which stress engagement in intellectual work of any kind, whatever its relation to power, it seems obvious in retrospect that Underhill and the sixties left were both wrong about the absence of intellectuals in Canadian history. Modern scholarship has turned up many previously little known figures, in the nineteenth as well as the twentieth centuries, who look very much like intellectuals: men and women like W.D. LeSueur, Phillips Thompson, Charles Clarke, Flora MacDonald Denison, and Francis Marion Beynon. Re–discoveries aside, the definitions both parties used appear narrow and self–referential. In the 1920s and 1930s, Underhill fixed on the idea of the intellectual as a political dissident and sought predecessors on the liberal democratic left. Sixties radicals, more interested in systematic analysis and theory, sought out earlier Marxists and proto–Marxists as models.

Like the word ‘ideology,’ however, ‘intellectual’ is a term whose uses and meanings have varied widely, with the result that it is more useful to ask what it represented in particular contexts than to deem certain uses of it ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ according to some fixed definition. In its nominative form it was a specifically twentieth–century representation of the relationship between the life of the mind and life in the world that has had a long and complex history in Western societies. Emergent in the years from the Dreyfus Affair to the aftermath of the Bolshevik Revolution, its use was conditioned by broadly left–wing disenchantment with the modern state and by the fears that this disenchantment aroused. As Stefan Collini has argued in his study of the word’s use in twentieth–century Britain, referred to earlier, pursuit of a fixed definition – a prescriptive or ‘stipulative’ definition – is fruitless and potentially misleading, since the word has had a surprisingly complicated history even as a singular and plural noun, despite its comparatively short life in those grammatical forms. Underhill’s use of it tells us as much about him as it does about the phenomenon he was wanting to describe.

Collini distinguishes three overlapping uses of the word, historically, in English (its cognates in French – intellectuel – and Russian – intelligent, pronounced with a hard ‘g’ – having their own histories): its use in a sociological sense, denoting a socio–professional category, such as journalist or teacher; its use in a subjective or normative sense, either positively or negatively, implying a certain attitude and posture toward the life of the mind; and its use in a cultural sense, referring to those who turn their knowledge or expertise to a public purpose beyond their own specialized field, in doing so evoking some “uncommanded response.”

These categories are similar to those put forward by Peter Allen in an earlier study of nineteenth– and twentieth–century usage: a university–educated person (which Collini expands somewhat in his first sense), a “devotee of culture” (rather like Collini’s second), and a cultural expert (refined in Collini’s third). It is striking that neither of these taxonomies provides even a separate category for the disaffected political thinker, much less gives it priority. Allen dismisses this sense of the word as too “eulogistic,” undermining its usefulness for “objective definition.” Collini is more circumspect, being suspicious of objective definitions in any case. He concedes that, while there might be an argument for a fourth ‘political’ sense, and while the French intellectuel (and even more so the plural les intellectuels) implies an interventionist political posture in its dominant sense, in English this is less a ‘sense’ than a ‘claim,’ a conclusion similar to Allen’s, but one which leads Collini to give the claim a significant place within his third, ‘cultural’ sense.

Collini’s method is immensely useful, and even crucial to our understanding. On the one hand, it is to attend to change and context, which is to say, to approach ‘the intellectual’ historically. On the other, it is to treat the term as part of a semantic field, in which the referent of one particular use of the term – its ‘meaning’ – is coloured by the referents of other uses of the term. Partly, this is simply to have an ear for connotation, and to recognize that it is preferable, because more informative about both use and user, to retain the accumulated connotations of a word than to strip them from it in the interests of establishing a neutral and universal meaning. (This is also true of other terms, such as ‘the West,’ ‘civilization,’ the above–mentioned ‘ideology,’ and, in another dimension of Underhill’s thought, ‘liberalism.’) One meaning of ‘the intellectual’ cannot be isolated, but will always incorporate elements of other meanings, or of entirely different, but related, words. In Underhill’s case, for example, in a move typical of his rhetorical technique, he drew the sting from the pejorative terms ‘highbrow’ and ‘egghead’ by simply adopting them as self–descriptors. In doing so, however, he acknowledged the broad cultural sense under which Collini argues the political sense of ‘intellectual’ belongs. Neither highbrow nor egghead refers to political intervention; rather, they suggest high intellectual achievement accompanied (in the first case) by airs of superiority, or (in the second) by a narrow constriction of personality.

Underhill’s use of ‘intellectual’ varied, as we have seen. He used it in a traditional manner – tradition, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, dating back to the early seventeenth century – as an adjective describing matters of intellect and understanding: ‘intellectual tradition,’ ‘intellectual maturity,’ ‘intellectual vitality,’ even ‘intellectual garage mechanics.’ His use of it as a noun, either singular or plural, was most commonly in the political sense (or claim), but this shaded easily into the sociological (‘the academic man,’ professors) and the subjective, as audience and occasion suited, and sometimes both at the same time (‘people like you and me’).

Even in his seemingly more narrow political usage, the word sometimes carried connotations suggestive of neighbouring meanings; for example, the idea that intellectuals were generalists, rather than specialists, that they (nevertheless) drew on their expertise in arriving at their judgements, and that their authority (like Siegfried’s) derived from their impartiality. Sometimes these meanings were contradictory, notably the idea that intellectuals were impartially critical, yet at the same time proponents for particular causes and points of view, a contradiction only resolvable if we accept the claim often implicit in Underhill’s earlier writings, that a truly objective analysis would lead anyone to agree with, and support, the LSR, if not also the CCF.

At the centre of his usage (and that of the sixties left), the noun ‘intellectual’ was a badge of identity, even a badge of honour won on the battlefield of political conflict; hence, Collini’s contention that in its political guise it is best understood as a ‘claim,’ rather than a ‘sense.’ The notion that Canada had few intellectuals – or none – served the purpose, whoever promoted it, both of encouraging nurture of the type in the interests of elevating public discourse, and of rescuing the promoter, at least potentially, from a state of under–appreciation. This was a strategy commonly deployed by intellectuals, as Collini shows, even among the archetypal French. The New York intellectuals associated with the Partisan Review bemoaned the immaturity of the American intellectual tradition in the 1930s and 1940s in terms very like those Underhill used to describe Canada, while intellectuals all over continental western Europe, as well as in Great Britain, lamented the relative weakness or absence of their like in their own countries – relative, that is, to France. The belief that things were better elsewhere was a staple of intellectual discourse.

It might even be to one’s advantage to exaggerate one’s neglect. Underhill seems to have done so, though to say as much is not to downplay the very real pressure placed on him to moderate, and even to suppress, his criticism of British imperialism and sympathy for North American isolationism in the late 1930s. Given his belief in the virtues of heresy, it was humiliating for him to have to promise the president of the University of Toronto, Canon H.J. Cody, that he would refrain from public comment on Canada’s international relations, as he was twice forced to do. In this case, the Common Man of A Man for All Seasons was not so common, and Underhill came very close to losing his job. At the same time, students, colleagues, and influential friends rallied to his defence, and newspapers across the country commented unfavourably on the infringement of Underhill’s freedom of speech. In another case of professorial dissent in the early thirties, Sir Arthur Currie, Principal of McGill University, hesitated to dismiss an outspoken young lecturer in political economy, Eugene Forsey, partly because he feared such an action would evoke widespread disapproval. Professors, it would seem, were taken seriously in the public sphere.

Later, when Underhill continued to complain of the low regard in which intellectuals were held, going so far as to suggest at a retirement luncheon for the CCF politician M.J. Coldwell in January 1962, that the intellectual level of Canadian politics had actually been declining for most of his adult life, there was considerable evidence to suggest otherwise. Around this time, his own columns and book reviews appeared frequently in the Toronto Star, the Globe and Mail, the Winnipeg Free Press, and other newspapers. In 1955, Ralph Allen, the editor of Maclean’s magazine, had told him that a couple of articles Underhill had sent him, including his Dunning Trust lecture at Queen’s University, “Canadian Liberal Democracy in 1955,” were a little too academic, but that the magazine needed thoughtful articles on controversial subjects. A few months later, Allen invited Underhill and a long list of other academics and journalists to submit “think pieces” of 1500–3000 words in length for possible publication in the magazine.

Even earlier, Underhill and other historians, such as A.R.M. Lower, had contributed frequently to the popular press, as well as to more limited circulation periodicals, and their books had won Governor–General’s medals for non–fiction. In 1966, the Toronto Star columnist Robert Fulford, reviewing a collection of essays by an intellectual of a younger generation, Ramsay Cook’s Canada and the French Canadian Question, began by saying that historians were “the great social thinkers of Canada, the people who shape our souls and define our aims.” Underhill was one of them; others included Donald Creighton, Laurier LaPierre (on CBC television’s This Hour has Seven Days), and William Kilbourn.

Underhill’s deflationary comment at the Coldwell luncheon was undoubtedly provoked by the fact that, in 1962, the prime minister was John Diefenbaker, whom he regarded as a classic anti–intellectual populist of the kind that Richard Hofstadter had criticized, which shows again that his use of ‘intellectual’ served polemical as well as descriptive ends. It also seems likely that he found in the category of the intellectual a means of distancing himself from the professionalization of his discipline, and of Canadian academic life in general, that began before the First World War and quickened its pace in the decades immediately following. Underhill had no Ph.D. at a time when it was becoming the premium qualification for a professorial appointment in Canada, as it had already become the standard in the United States. The defining features of an intellectual – the widely read generalist, engaged in public issues, concerned more with education than with training, and committed to the making of statesmen rather than to the production of ‘research’ – offered an alternative to the authority of the expert that was closer to the nineteenth–century ideal of the public moralist, though implying a greater measure of alienation. There was, in short, an undeniable element of self–interest in Underhill’s representation of the intellectual.

Similarly, however, Collini’s insistence on demoting the political sense of intellectual to a subsidiary status seems not without its own element of polemical intent. He is himself an eminent contemporary English intellectual, impatient both with the persistence of the English myth that ‘the intellectual’ is a species only to be found elsewhere, and with the sometimes self–dramatizing and self–aggrandizing rhetorical practices of explicitly dissident intellectuals of his own day. He begins his chapter entitled “Outsider Studies: The Glamour of Dissent” by referring to “the satisfying thrill, the subtly self–flattering frisson of excitement’ of thinking oneself an outsider when, in fact, those who have achieved the reputation and audience necessary to the role of an intellectual are inherently within society and hardly to be classified among ‘the neglected and outcast of history.” This seems itself to be overly tendentious, since few intellectuals think of themselves as literally outside society. Certainly Underhill did not; he thought he was outside the centres of political and economic power. It is true that he put himself there, at least to some degree, and also that he exaggerated his outsider status, but it is also true that his disaffection framed his perspective on politics and defined his sense of identity. However subjective his feeling may have been, it helped to shape his role as an intellectual. One wonders, in fact, if Collini’s distinction between disaffection as a claim made by some intellectuals, and as a particular use of the term ‘intellectual’ is not too fine to be maintained.

Underhill’s outsider status was not only subjective. If we turn his crisis at the University of Toronto to the aspect of his silencing, rather than to the aspect of his defence – they are both aspects of the same crisis – it appears that some senior provincial politicians and university officials would certainly have preferred to make him an outcast. He found some relief in a year’s leave of absence on a Guggenheim Fellowship, which he took up in New York – not exactly deprivation, as Collini would doubtless point out. Nor was Underhill’s ulcer condition, which was certainly worsened by the affair, comparable, say, to what intellectuals suffered in the contemporary Soviet Union; but the bar of punishment worthy of being considered approximate to neglect and ostracism ought not to be set too high. The question, in any case, is not so much whether Underhill’s internal experience of the affair merits his being labelled an intellectual – it left him “drained and embittered,” in his biographer’s words – as whether his actions and their impact, in their particular setting, had a cultural and political significance that calls for application of the term, and whether his subjective experience is a part of that significance.

Collini would prefer to restrict what he calls the “structure of relations” governing the role of the intellectual to external variables – achievement in an intellectual field of endeavour, access to means of communication for reaching a public (or publics) beyond that particular field, expression of views that connect in some way with the interests of those publics, and establishment of a reputation for being able to communicate interesting and worthwhile things to them. The elusive quality of cultural authority is located where these elements intersect, he argues, and enables the phenomenon of ‘the intellectual’ to manifest itself. This is a flexible enough model to accommodate widely varying circumstances, yet it achieves its flexibility at the cost of sacrificing some of its power to capture the particular phenomenon of the intellectual in the twentieth century, face turned, Janus–like, in one student’s words, “both towards the study and towards the street.” Confidence in the public importance of one’s own ideas, belief in one’s capacity to communicate them, and willingness to withstand the criticism they necessarily evoke as a result of their oppositionist character, amount together to a subjective pre–requisite to assumption of the posture of ‘the intellectual’ and ought to be included among its structural conditions.

No historical account of the intellectual, whether Collini’s or Underhill’s, can escape its author’s own presuppositions, especially if he or she is also an intellectual, or sees himself or herself as one. In my own case, I may be unable to remove entirely my early imported associations of the term ‘intellectual’ with the pre–revolutionary movements of nineteenth–century Russia; I am certainly unable to think of the intelligentsia as merely the “chattering classes,” which has become one of its modern meanings. This may dispose me to scepticism toward such arguments as Collini’s or Allen’s that relegate the political sense of ‘intellectual’ to subsidiary rank. Underhill’s pre–eminent position in the twentieth–century history of intellectuals in Canada – his own career traces one of its most important chapters, misapprehensions of the sixties left notwithstanding – is evidence, however, in support of recognizing disaffected political thought and action as a distinctive use of the term in its own right.

In recent times the term ‘public intellectual’ has emerged to distinguish the politically engaged intellectual from others, which is an indication both of other uses of ‘intellectual’ and of its widespread acceptance as a descriptor of a recognizable type. The term no longer appears within quotation marks in ordinary usage, nor is it used self–consciously in contemporary discourse, both marks of its use in a changing semantic field. At the same time, there has been much talk of “the end of the intellectual,” especially in the United States. I am reluctant, myself, to speak of the end of the intellectual at a time when, even in liberal democracies such as Canada, the expression of public criticism of a government can get one into trouble, even to having one’s employment threatened. At the same time, it seems foolish to me to suggest that the action of radical public criticism in an age when it is commonplace is culturally identical to the same action when it is rare. The fact that it is commonplace today owes much to the example of Frank Underhill, but in helping to establish ‘the intellectual’ as a cultural figure, he also helped to transform its meaning. For Underhill, and very many of his contemporaries, the term ‘public intellectual’ would have seemed a redundancy.