|

Theatre Survey 50:1 (May 2009)

2009 American Society for Theatre Research

doi:10.1017/S0040557409000076

Emily Sahakian [See note]

FRAMEWORKS FOR INTERPRETING FRENCH

CARIBBEAN WOMEN'S THEATRE: INA CÉSAIRE'S

ISLAND MEMORIES AT THE THÉÂTRE DU CAMPAGNOL

The plays and performances of French Caribbean women, which have mostly been examined in the French language and in the field of French literary studies, [1] require a new theorization of postcolonial theatre. Highly influenced by what I call French universalism, French Caribbean women's theatre moves continuously between evoking Caribbean and gender difference and mobilizing the concept of the human universal. Their work enacts a restorative postcolonial women's agenda that is specific to the cultural context of the French overseas departments of Martinique and Guadeloupe.

The 1983 production of Ina Césaire's pathbreaking Mémoires d'Isles or Island Memories and its reception by a culturally mixed audience are my focus in this essay. My interpretation-like the production-moves between two frameworks for understanding cultural difference. Indebted to VèVè Clark's concept of marasa consciousness, in which signs are read not in a Hegelian dialectic but through a cyclical, spiral relationship, [2] I investigate the ways that the play spoke differently to multiple audiences, reading Island Memories as a postcolonial production that cycled (a verb I use to evoke Clark's concept cited above) between the designations of French-Caribbean, colonizer-colonized, and man-woman as well as between theoretical frameworks for interpreting cultural theatre. Scholarly analysis of postcolonial theatre opens up interpretations of Island Memories as a rewriting of history and an assertion of Martinican difference, through references to Carnival and traumatic colonial histories. [3] However, the concept of the human universal, which is generally conceived in English-language scholarship as at odds with postcolonial agendas, is also crucial for understanding the production and its reception. My analysis points to the ways that the particular situation of women writers in the French overseas departments of the Caribbean engenders a postcolonial theatre that rewrites the notion of cultural difference. It thus provides a salient example of how national context and local gender politics influence the theoretical paradigms we mobilize to interpret postcolonial and women's theatre and performance.

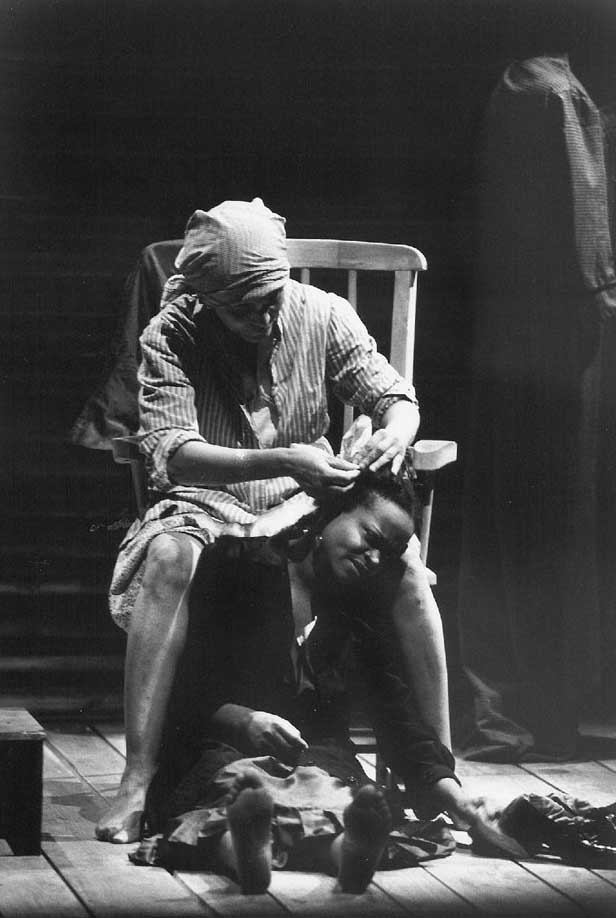

Island Memories was first produced in 1983 at the Théâtre du Campagnol in Bagneux, a suburb of Paris, where it was directed by Jean-Claude Penchenat and starred French Caribbean actresses Mariann Mathéus and Myrrha Donzenac. The play begins with a prologue that draws on the inherently subversive potential of Carnival traditions. After the prologue, the two actresses move to a makeup table onstage: a metatheatrical moment where spectators witness the women's transformation into the play's two half-sister protagonists. The play's dialogue, or "monologues," as Césaire puts it, [4] is based on testimonies that Césaire had been collecting since 1980 that documented memories of almost a century of Martinican lived history from the point of view of women. [5] It consists of the reminiscences of two grandmothers as they sit together outside a wedding celebration on a veranda. Aure, an educated blue-eyed mulattress [6] from the South, and Hermance, a tall working-class black woman from the North, share their memories, telling personal stories of childhood, family, marriage, and loss (Fig. 1). Intertwined with their personal hardships, triumphs, and lessons are references to larger events and periods in Martinican cultural memory, such as the mob killing in 1870 of a white juror who had convicted a black man in a controversial racialized trial, [7] the great hurricane of 1928, [8] and the resistance movement against the German occupation of France during World War II. [9] Through their stories, the two women "remember the past and reinscribe the history of the island under the sign of women's quotidian reality," in the words of Christiane Makward and Judith Miller. [10] The dialogue, largely in French, is accentuated with expressions in Creole.

My methodology for interpreting this play rewrites theories of postcolonial theatre by taking into account French Caribbean women's understandings of cultural identity. Martinicans and Guadeloupeans identify as both French and Caribbean and thus lay claim to a French universalism that largely ignores cultural difference. Moreover, French Caribbean women writers deploy this French Theatre Survey universal in order to reconcile a conflicted relationship between Caribbean women and men. This French Caribbean women's worldview complicates understandings of a postcolonial theatrical agenda, which is especially evident when we view their work using conceptions of postcolonial and intercultural theatre.

Photo: Alain Fonteray

Myrrha Donzenac and Mariann Mathéus on André Acquart’s set for Island Memories.

Island Memories reveals the restorative potential of a production that continually cycles between modes of conceiving of cultural difference and shared humanity. Suzanne Crosta [11] deems Island Memories "theatre-therapy," arguing that the play helps Caribbeans work through and transform cultural trauma and generates empathy from French viewers. An analysis of the ways that the production cycled between languages and theatrical conventions in order to speak differently to different audiences reveals this restorative potential of the play. After seeing the play, scholar of Caribbean theatre Bridget Jones remarked that "more than one participant used the word 'grace' for the sense of communion achieved." [12] Although the production was accessible to all, spectators interpreted the production in different ways through their own cultural expectations and linguistic abilities. [13] I divide the spectators of this production into two groups: the French of the hexagone and the French Caribbeans of Martinique and Guadeloupe. Moving between Martinican cultural difference and the human universal, subversion and acceptance, Island Memories resists French cultural supremacy and provides a communal and restorative theatrical event. It thus carves out a space for a postcolonial women's agenda in Martinique.

FRENCH CARIBBEAN CULTURAL POLITICS AND THE PROBLEM OF THE UNIVERSAL

The islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe present a unique situation in terms of cultural politics and strategic responses to neoimperialism.Whereas Haiti fought and won independence from France in 1804, the islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe, which have been part of France for over three hundred years, still hold the official status of French overseas departments. This status dates from a controversial law for départementalisation that was drafted by Aimé Césaire (Ina’s father) and passed in 1946. Caribbeans living in these islands are French citizens. Thus, they have the same legal rights and privileges as the population labeled français de souche, a problematic reference to (white) descendents of French ancestry. Indeed, Martinicans and Guadeloupeans are French, and they commonly identify as both French and Caribbean. [14] However, identifying as French involves a trade-off, or what anthropologist David Beriss calls “the price of Frenchness,” [15] since French society idealistically denies the import of racial and cultural difference. In other words, Caribbeans and other minorities are asked to give up cultural particularities, values, and customs in order to assume a cultureless and raceless French identity. What I call French universalism refers to a system that pervades all levels of society, emphasizes unity within shared Republican values, and disparages both cultural difference and solidarity within ethnic communities. Historically, this phenomenon can be traced to a cultural consciousness that grew out of the French Revolution as well as a shared national sentiment in the aftermath of World War II that rationalized that the way to avoid the horrors of ethnic massacres or genocide was to deny the existence of race altogether. Linked to French elitism, education, and (what is perceived of as) high culture, the allure of Frenchness is enticing, yet it comes with a heavy price. Moreover, the notion of undifferentiated identity is obviously flawed: in France there is insidious discrimination and racism that is only just now, since the riots of 2005, beginning to be widely recognized. For years, unequal power imbalances in France were understood solely within the rubric of class hierarchies. The category of race and the potential problem of racism have only just begun to enter French academic and popular discourse. [16] At the time of the production of Island Memories, the Martinican population in France dealt daily with the paradox of self-identifying as both French and Caribbean in a society that refused to recognize certain kinds of racial or cultural difference as part of the category of “French.”

French Caribbean thought, art, and politics are characterized by an ambivalent negotiation between claiming universalist Frenchness and asserting Caribbean difference. [17] For years, many French Caribbeans believed that successful assimilation into French society would be the solution to the power imbalance of the colonial legacy. Indeed, Martinican and Guadeloupean cultural organizations, such as l’Association CIFORDOM, a resource center for residents of the overseas departments living in France, still embrace this objective of assimilation, or what they call integration. The problem with this objective, however, is that it inevitably requires a denial of parts of Caribbean culture. In the words of Jean Bernabé, Patrick Chamoiseau, and Raphaël Confiant - the Theatre Survey Martinican authors of the renowned Créolité movement - Caribbeans were led to “beg for the universal in the most colorless and scentless way, i.e. refusing the very foundation of our being.” [18] Yet the problem with asserting difference is that the evocation of cultural or racial difference in France and within the French Caribbean community can commonly be seen as racist or condescending. David Beriss summarizes: “Racism in France is not principally defined by attention to color or by the deployment of racial stereotypes (although it can be). Instead racism is understood primarily as an incorrect or unjust invocation of culture.” [19] Whereas affirming difference is a necessary political act for French Caribbeans, it is also a way that they make themselves inferior: many French Caribbeans see the relegation of Caribbean culture or art to an ethnic or historical particularity as a form of ghettoization. Although English-language scholars’ valorization of the political efficacy of evoking difference can illuminate this postcolonial situation, the practice does not correspond well to the situation with which French Caribbeans are faced. While they are helpful, English-language conceptions of cultural difference do not fit the French Caribbean context well. Éric Fassin highlights this point in the French context, noting that what is deemed the American (or sometimes Anglo-Saxon) worldview has served both as a model and countermodel in discourse on immigration and ethnicity in France. [20]

Women in the French Caribbean have often been associated with Frenchness or regarded as at odds with anticolonial nationalistic movements in the Caribbean. A. James Arnold has called attention to the sexualized nature of the system of domination that was slavery and colonialism. According to Arnold, this “erotics of colonialism” gave rise to two separate literary cultures in the French Caribbean that are divided along gender lines. [21] Ellen M. Schnepel demonstrates how French Caribbean mothers are caught between the dominant French ideology and an oppositional nationalistic one. [22] By showing a link between respectability and language choice, Schnepel introduces the notion of gendered uses of Creole and French. Linking language choice to sexuality, she explains that Creole is often associated with virility and vulgarity; to pick up women on the street, men speak in Creole, but to court women, they speak in French. [23] Examining mothers’ relationship to these two languages, Schnepel suggests that mothers might reject Creole in favor of social mobility for their children and thus be seen as opposing an effort to affirm a local identity. French Caribbean women writers address this difficult situation, rewriting not only colonial history but also the relationship between Caribbean women and men. Ina Césaire’s ethnodramaturgy has the very clear objective of rewriting women into Martinican history and reclaiming the once-misogynistic tradition of storytelling, or contes. [24]

FRENCH CARIBBEAN THEATRE AND THE POSTCOLONIAL - INTERCULTURAL COMPARISON

At the theatre, artists stage, criticize, and rewrite the notions of French universalism and Caribbean difference. For Édouard Glissant, theatre is definitive for the formation of a nation, “the act through which the collective consciousness sees itself and consequently moves forward.” [25] In the words of Bridget Jones, Frameworks for Interpreting French Caribbean Women’s Theatre theatre is “a privileged arena, a site where the paradoxical strains of dependency and difference can be enacted.” [26] Jones points out that the 1983 production of Island Memories was staged in the context of increasing anxiety about affirming Martinican identity in the face of a French culture that permeated Martinican society. This produced efforts to develop local talent and build up a Martinican repertoire. [27]

But how to characterize the Martinican repertoire is a question that has inspired controversy and debate. Theatre artists both vehemently refuse and believe deeply in such projects as exploring African roots, validating métissage (the cultural mixing characteristic of Caribbean society), and evoking the memory of slavery. French Caribbean theatre can take on many different labels and designations. Alvina Ruprecht’s introduction to a book that brings together Francophone and Creolophone theatres tries on different designations, such as French, Caribbean, black, and “Theatre of the Americas,” pointing to the advantages and disadvantages of each. She emphasizes the particularly problematic nature of the category “Francophone,” which puts France at the center. [28]

The power of French cultural supremacy, even in Haiti, should not be underestimated. For instance, Ruprecht suggests that if contact between the Francophone and Anglo or Hispanophone Caribbean theatres is not developed, it is not only because of the linguistic barrier but also because of the problem of the French theatrical tradition, which highly influences Caribbean societies, even in a postcolonial era. [29] Because France’s influence distances these islands from their West Indian neighbors, efforts to think about Martinique and Guadeloupe as part of the Caribbean are politically justified. It is also important, however, to conceive of French Caribbean theatre in terms of its unique departmental status. The fact that these islands are still part of France, for better or for worse, dictates how they enter into a larger Caribbean community. A concrete and telling example of this is that even though artists such as Annick Justin Joseph and José Exélis have attempted to make the cross-island theatrical links that Ruprecht hopes will be developed, unequal financial resources can complicate the exchange. As actress and cultural advisor Aurélie Dalmat explained to me, while Martinican theatre artists are often subsidized by the French government, their artistic partners in neighboring islands have significantly smaller theatre budgets. Thus Martinicans must pay more than their partners if these cross-island theatrical exchanges are to get off the ground. [30]

Martinique and Guadeloupe can be conceived of as postcolonial nations, and Island Memories represents a postcolonial production. Margaret A. Majumdar has recently argued that a theoretical gulf has emerged between Anglophone and Francophone thinking regarding postcoloniality. [31] The artistic objectives of and the reception of postcolonial theatre in the Francophone context require a theoretical framework that takes into account the pervasive influence of French universalism. This force of the universal is especially prevalent in the overseas departments and is conspicuous in the work of women writers. Because Martinican and Guadeloupean women have historically been associated with Frenchness, mobilizing this universal can become a strategic artistic tool to Theatre Survey address the ongoing relationship to France. Noting use of the universal as a literacy device thus helps to tease out the differences between men and women’s writing.

In their pivotal study of postcolonial drama, Helen Gilbert and Joanne Tompkins define postcolonialism as an “engagement with and contestation of colonialism’s discourses, power structures, and social hierarchies.” [32] The discourses, power structures, and social hierarchies of colonialism in the French Caribbean postcolonial situation are insidious. The power-based binary of “us” and “them” that postcolonial theatre characteristically aims to dismantle, according to Gilbert and Tompkins, is especially slippery there. [33] In Martinique and Guadeloupe, imperialism has blended into a neoimperialism that blurs French and Caribbean subjectivities; a certain mobility between the two identities is both desired and vindicated by Caribbeans and tolerated (if with limitations) by neoimperial cultural powers. [34] Readers must remember that Ina Césaire is an educated upper-class woman whose father’s literary work is well respected in France, where “literary geniuses” are thought of as transcending cultural designations. On the subject of identity, Ina Césaire has said:

We are no longer at the level of “Who are we?” ... “What is our identity?” Identity is. Personally, I no longer ask myself the identity question, I feel it very profoundly, without anxiety, without bitterness. ... That can’t be assimilated! When I read Dostoevsky, I’m not Russian, but I can enter into the skins of the characters in The Brothers Karamazov, and I’m passionate about it! I love Chekhov! So I believe that anyone can understand the soul of a Caribbean if he takes the time to penetrate it (and let it penetrate him) himself. [35]

To a reader immersed in English-language cultural studies, two aspects of this statement may seem surprising: first, that Ina Césaire needs to quiet anxiety about her identity being assimilated or lost, and second, that she seems to subscribe to a sort of universalism of literature, to assert that anyone, regardless of culture, can enter into the soul of another person or character. These suggestions are in fact at odds with typical theories of postcolonial theatre, which are based on the existence of a postcolonial, black, indigenous, or syncretic subject position. Ina Césaire identifies as both particular and universal. The stories of Martinican women position her historically and socially, while her embrace of an undifferentiated and culturally universal category allows for the possibility of her “greatness” or “genius” as an unmarked artist. Césaire makes both “French Caribbean women’s theatre” and “theatre.”

Examining the different views and perceptions of intercultural theatre reveals the vital difference between the theoretical frameworks that are available for interpreting postcolonial theatre and a new framework that fits the work of French Caribbean women playwrights. English-language theatre scholars have forcefully differentiated between “postcolonial theatre” and the tradition known as “intercultural” (or sometimes “anthropological”) theatre, an appropriation of a foreign story or art form commonly associated with European artists Peter Brook, Ariane Mnouchkine, and Eugenio Barba. [36] For Gilbert and Tompkins, the major Frameworks for Interpreting French Caribbean Women’s Theatre problem with intercultural theatre is that it “aim[s] to enumerate similarities between all cultures without recognizing highly significant differences.” [37] The most controversial intercultural work is Peter Brook’s Mahabharata, an adaptation of the great Indian epic performed by an international cast. Indian critic Rustom Bharucha has claimed that Brook failed to incorporate the Indian cultural context and instead evoked a conceptually fuzzy and poorly informed “flavour of India.” [38] Additionally, Bharucha criticizes Brook’s intercultural method of research in India, [39] citing in particular the reportedly disrespectful personal and financial interactions the company had with the Indian artists from whom they borrowed. Brook, however, feels that he is not borrowing from or enacting Indian culture but rather attempting to uncover an underlying human universal truth - what he calls a “third culture” or “culture of links” - that will be unveiled only through endless discoveries of relationships and breakings of stereotypes. [40] In other words, Brook is not concerned with Indian culture itself but with its relationship to other cultures, which he stages by reinterpreting the Mahabharata with his international multilingual cast. Brook’s objective exemplifies the kind of intercultural or anthropological theatre that Gilbert and Tompkins disparage:

As well as ignoring the differences among and between peoples who have been colonised, the anthropological approach to theatre also moves perilously close to universalist criticism whereby a text is said to speak to readers all around the world because it espouses, for example, universal principles of life. Texts which apparently radiate such “universal truths” have usually been removed from their social and historical setting. Although it is a favourite catch-cry of theatre critics, the “universal theme” allows no appreciation of cultural difference. [41]

This statement from probably the most influential text on postcolonial theatre criticizes a universalist discourse that comes surprisingly close to Ina Césaire’s comments on identity. However, while Gilbert and Tompkins associate the universalism they disparage with theatre critics who, we can presume, take universality for granted by virtue of their personal cultural standpoint, Ina Césaire rewrites the French universal through a diasporic marasa consciousness. Moreover, unlike an evocation of the universal in an ahistorical vacuum, her rewriting of the universal is undeniably linked to the cultural politics of Martinique and Guadeloupe and to the situation of women on the islands. Thus standpoint separates postcolonial theatre from intercultural theatre. Christopher Balme, who theorizes postcolonial theatre as “syncretic,” is interested in “the appropriation of the Western model of theatre and drama by the colonized people themselves.” [42] For Balme, postcolonial theatre is intercultural in form but differs from intercultural theatre because it is political and is created from a postcolonial location or standpoint. [43]

While English-language scholars draw a line between intercultural and postcolonial theatre, either claiming that postcolonial theatre asserts difference or is political and written from the position of the “colonized,” French Caribbean women playwrights do not make these distinctions. Renowned Guadeloupean novelist and playwright Maryse Condé was influenced by Ariane Mnouchkine, Theatre Survey whose radicalized performance of the French Revolution, 1789, encouraged Condé to create An tan revolisyon (In the Time of Revolution). [44] This play is her own rerendering of Haitian and Guadeloupean history, dramatizing the events of of 1789–1802: news of the French Revolution reaches the colonies, emancipation is declared, and Toussaint L’Ouverture is given power, and then slavery is treacherously reinstated by Napoleon and Toussaint L’Ouverture is arrested. Like Mnouchkine, Condé deconstructs great men (including Toussaint L’Ouverture), pokes fun at recognizable quotes, and gives voice to figures and histories that have been silenced. Condé also directly quotes tidbits of the most memorable scenes from 1789, and her set overtly referenced Mnouchkine’s set. [45] In the case of Island Memories (whose director, Penchenat, was a former member of Mnouchkine’s Théâtre du Soleil), Ina Césaire took her cue from Peter Brook. After seeing a production of The Ik, she commented that there was now room for her ethnodrama in the theatre scene: “I was inspired by the chance to take ethnology out of its ghetto of specialists and to give it back to those who are primarily implicated.” [46] These French Caribbean women writers resist the distinctions that theatre scholars make between intercultural and postcolonial theatre. By deconstructing Toussaint L’Ouverture, Maryse Condé avoided mocking only French or white Great Men and thus resisted a fixed standpoint of “colonized.” Likewise, Condé clearly positioned herself alongside Mnouchkine, and Ina Césaire associated herself with Peter Brook. Césaire’s desire to take her ethnodrama out of the “ghetto” of specialists might be interpreted as a hope of universalizing her ethnographic data on Martinican women.

INTERPRETING FRENCH CARIBBEAN WOMEN’S THEATRE AS POSTCOLONIAL

In order to ask how the production of Island Memories accomplishes a new postcolonial agenda, I analyze the play text, the production program, and critical articles and reviews. [47] Here “universalism” becomes a methodological concern. Moving between frameworks for conceiving of cultural difference and shared humanity, I must both recognize difference in terms of how a performance communicates meaning and is received by spectators and point out that the different groups that I will generalize into two categories may read as deceptively fixed. Although this is true for any theatrical production, it is crucial for the production of Island Memories, as audience members to whom I will refer as “Caribbean” may have identified as either French or Caribbean or (most likely) both. The terms “French” and “Caribbean” as I use them are certainly problematic. However, for the purpose of revealing Césaire’s postcolonial message, I will nevertheless identify these two groups of spectators: “French” of the hexagone and “Caribbeans” of Martinique and Guadeloupe living in France, whom we can also understand as the French of Caribbean origin. Christiane Makward likewise identifies two targeted spectators: she characterizes the Caribbean audience as “fastidious, we can expect, on questions of politics, linguistics, and skin-tone,” [48] while the French audience is “open-minded [if they chose to go see the play] but modest, poorly informed of Caribbean Frameworks for Interpreting French Caribbean Women’s Theatre realities, and possibly touchy on a patriotic soft spot.” [49] We can assume that Martinican and Guadeloupean audience members were well versed in French and the Western theatrical language and that there were thus no comprehension problems for Caribbeans. The French audience, on the other hand, was likely poorly informed about the tradition of Carnival and did not speak or understand Creole apart from the amount of comprehension that can be gleaned from its similarities with French. [50]

It is possible that some of the French audience members had seen performances of certain plays written by French Caribbean authors. Those few spectators familiar with this repertoire most likely had seen performances, directed by the widely respected Jean-Marie Serreau, of Césaire’s father’s trilogy, which was written in French and relied heavily on European theatrical traditions, often referencing Shakespeare. [51] It is also possible that a (smaller) minority had seen productions of plays such as Daniel Boukman’s Les Négriers, written in French and performed in 1972 at the Théâtre Daniel Sorano in Paris, or of Édouard Glissant’s Monsieur Toussaint, which was performed in 1977 at the Cité Universitaire de Paris and made use of some Creole although it was written mostly in French. Nonetheless, I hypothesize that it was unlikely, in 1983, that many audience members had seen plays written by French Caribbean playwrights. It is likely, however, that many of the French spectators were familiar with the work of Peter Brook or Ariane Mnouchkine, who was working on her Shakespeare cycle at the time, and thus used intercultural theatre as a framework for interpreting Island Memories. Penchenat’s artistic trajectory makes this scenario even more likely.

Unlike the work of Mnouchkine and Brook, which does not require certain cultural competency or literacy for its interpretation, Ina Césaire’s theatre operates along the lines of Christopher Balme’s theorization of the semiotics of postcolonial drama: it is divided into two discrete semiospheres in which semiosis takes place on different levels. [52] However, the French spectator, accustomed to intercultural or anthropological theatre, was probably not expecting the “Caribbean” semiosphere. The French spectator was more likely anticipating song, dance, or performance of ritual that was not meant to be understood in its cultural context, as in Brook and Mnouchkine’s anthropological creations. But the production of Island Memories, in which French audience members were seated next to French Caribbeans who had the cultural competency needed to interpret both semiotic codes, challenged these expectations, forcing French spectators to recognize the “Caribbean” semiosphere. The production thus challenged French universalism and the problematic use of the universal spectator during anthropological or intercultural theatre performances.

Island Memories unveiled or “demasked” - to use Gerard Aching’s theorization of a carnivalesque political tactic [53] - these two audiences, which were otherwise invisible in a French society permeated by the ideology of universalism. However, the production did not, as in other examples of postcolonial theatre, aim to place these two groups in opposition to one another. [54] Island Memories forced the French spectator to accept Martinican difference, Theatre Survey making space for Caribbean culture within a conception of Frenchness in which culture and race had previously been dismissed and ignored. The desired result is a restorative postcolonial theatre that aims to accept the past while rewriting it; as Césaire wrote in the end of the prologue to the published text, “Tomorrow will be different!” [55] Island Memories evokes a marasa consciousness in which the cultural signs of Caribbean and French and men and women as well as the notions of universal and different are read beyond the binary in a cyclical, spiral relationship, and thus rewrites both Martinican history and the notion of the universal. Unlike the flawed French universal, the universal of Césaire’s Martinican women, which is defined by marasa consciousness, recognizes difference and rewrites limiting binaries. Island Memories thus enacts a theory of identity that is similar to Edouard Glissant’s notion of relation as created through ceaseless encounters with an Other. [56] Glissant asserts that this phenomenon of relational identity - or identity defined through relation - was started in the Caribbean but is now universally applicable to the whole world, which is becoming creolized. [57]

THE CREATION OF ISLAND MEMORIES

Island Memories was created collaboratively in the spirit of Jean-Claude Penchenat’s democratic theatre. While the collaborative team identified a director, author, actresses, and designers, asking each member of the team to play a certain role, each member also shared in aspects of the creation, offering each other insights and performing multiple roles. For example, the two French Caribbean actresses, Myrrha Donzenac and Mariann Mathéus, interviewed their grandmothers and offered the suggestion of adding the prologue. [58] Like Mnouchkine’s collaborative theatre, Penchenat’s process aims to dismantle traditional hierarchies of theatrical creation but does not do away with directorial artistic authority. Indeed, Penchenat explains that he left Mnouchkine’s Théâtre du Soleil because his experience as a founding member had whetted his desire to start his own company and implement his own directorial visions. [59] Ina Césaire met Penchenat in Martinique, where he was working on a reality-inspired film and play called The Bal. Realizing that there was space within the French theatrical scene for the testimonies of Martinican women she had been collecting, Césaire discussed the idea of the production with Penchenat. [60] Césaire, who received her doctorate in ethnology from the Sorbonne, where she studied African anthropology, described the older women in Martinique and Guadeloupe she had interviewed as “the memory of people and of cultures.” [61] Island Memories, which is dedicated to Césaire’s two grandmothers (who are discreetly honored as Maman N. et Maman F. in the play’s subtitle), is the issue of Césaire’s ethnological work, the improvisations of the actresses, and the directing eye of Penchenat (Fig. 2). [62]

Ina Césaire’s attitude toward the creative process cycles between universal and different in that it welcomes all collaborators openly into the process, relying on their various artistic and cultural competencies. While some may engage with the creation at a culturally specific or gendered level, others may interpret it at the more general level of the “human.” Césaire comments on this collaborative process. Complementing her efforts to write in the way that older French Caribbean women speak about their lives, the production drew upon

the acting of the actresses, who are Caribbean themselves, and who helped me by bringing their experiences and memories to enrich the text. They found gestures naturally; the research was pushed into the realm of life as well as the staging of Jean-Claude Penchenat, who is not very familiar - it’s true - with the Caribbean, although he offered himself up to our service. [63]

Photo: Alain Fonteray

Through improvisation, the two actresses reenact a memory from Hermance’s childhood.

Césaire recognized where Penchenat was limited yet made space for him to engage with the work within a different framework. Penchenat has described the production as dealing with “the mechanism of memory - something very dear to me!” [64] Island Memories is simultaneously the story of two characters who are “profoundly female, profoundly Caribbean” [65] and an exploration of a human biological mechanism, that of memory. Already at this level of artistic creation, we can observe multiple and simultaneous frameworks for interpretation. In such a dynamic creative process, Martinican reality is both counted as cultural particularity and given the privileged position of the human universal. Such a choice is an important postcolonial move in the French Caribbean context because it does not relegate Martinican culture to a necessarily historical political status that would deny the culture’s ability to interest those unfamiliar with it. In assigning a universal meaning to the complex, multifaceted, and yet unified reality of Martinican women, Césaire refuses the psychological oppression of French cultural supremacy while sharing Martinican women’s reality with a larger community. In a note in the program, Césaire explains that an ethnologist cannot reach people with her work unless she “comes out of her ghetto of specialists.” [66] Indeed, the production of Island Memories strives to come out of any “ghetto” in which it could be classified or entrapped.

THE PARADE OF SHE-DEVILS AND INTERPRETING CARNIVAL

The performance begins with the prologue, a Parade des Diablesses (Parade of She-Devils). Marking the last day of Martinican Carnival, the actresses are dressed in black and white as She-Devils of Ash Wednesday, companions of the Haitian loa Baron Samedi who are feared in the Caribbean because they are known to hide under bridges and spirit men away. [67] Baron Samedi, the loa of death, is always portrayed at the crossroads into the next life and therefore signifies a transition into a new world in which the past life, like the painful Martinican history in Césaire’s play, is accepted and moved beyond. During the prologue, the actresses address the audience directly, riddle, and dance the vide, a Carnival strut. The text of the prologue is variable, and the changes that Césaire made for publication move further into the realm of the French universal by replacing Creole with French and removing historical details (although other historical details have been added to the dialogue). The formulations of the prologue from the archival collection on the Théâtre du Campagnol at the Bibliothèque nationale de France are almost completely in Creole, with the exception of an account in French of Christopher Columbus’s “discovery” of the Caribbean. Beginning by opening the door to Carnival celebration, and thus marking a distinctive kind of theatrical creation with different rules for spectatorship, the She-Devils tell a dancing and riddling “history” of Martinique in Creole, mentioning well-known figures (such as French abolitionist Victor Schoelcher) and events (such as Napoleon’s betrayal of French Caribbeans by reinstating slavery in 1802). Christiane Makward, who was present at the production, observed a “crescendo” in Creole, marked by the shouting out of historical dates. Makward noted particularly the shouting out of the year 1870, which she argues takes the audience from the realm of history into lived memory. That is the year of the Southern Insurrection in Martinique, of which the titular protagonist of another of Césaire’s plays, Rosanie Soleil, the daughter of fire, is the heroine. [68] The published version of the prologue, on the other hand, which was rewritten by Césaire after the performance, moves back and forth between French and Creole. Keeping the introductory reference to the three hundred years of Martinican history but leaving out specific dates and figures, the text concentrates on the transformational power of performance (or lived memory). Claiming that the past has been trespassed, surpassed, and perhaps passed away, the actresses agree to go on dancing, claiming that “tomorrow will be different!” [69] The women then go to their makeup tables, where they transform themselves into Aure and Hermance, the elderly half-sister protagonists of the play.

The subversive potential of the play is rooted in this reference to Carnival, [70] which sets the rules by which spectators receive moments of doubling in the Creole language. Corresponding to Lent in the metropole, Carnival was celebrated each year on plantations during the time of slavery. Those few days were the only time off given to slaves, who took advantage of this celebration to “symbolically invert the ethno-social pyramid.” [71] Césaire describes the unique experience of Carnival in Martinique, at the same time pointing to the universal relevance of Martinican culture in her reference to “the primordial joy of masking.”

If you haven’t seen an Antillean Carnival, you don’t know what Carnival is. I’m not talking about the money-motivated debaucheries you see in Rio. People transform, it’s one day where all the men are women and the women are men, the sexes are inverted and the poor become rich. ... It’s the primordial joy of masking, you just take whatever you have at home. Your face painted, you don’t recognize anyone, it’s a different moment, a delirious one. [72]

Carnival is a time for celebration and dancing, a time for disguise, for pretending, a moment when hierarchies are inverted. The transformative power of Carnival, like the rewriting of history through performance, has been understood to have a healing potential. [73] The dancing body in Carnival (the major element of the prologue to Island Memories) has been known to unite people. [74] Additionally, Carnival holds the subversive power to unmask uneven or hierarchical subject positions and to reveal the ideological underpinnings by which viewing subjects recognize the masked. [75] In the context of a mixed French and Caribbean audience in the suburbs of Paris, the reference to Carnival unmasks racism and cultural discrimination and reveals the ways that these Caribbean realities have been denied by the ideology of French universalism. By enacting the lived reality of Martinican women in France within the context of French intercultural theatre while deliberately referencing French universalism, Césaire is simultaneously uniting her spectators and evoking a better universal than the flawed French one. Contrary to common practices in Western theatre, Carnival puts no barrier between performer and audience. Thus, the prologue asks the Caribbean spectator to participate as an agent in the reinscribing and re-creating of Martinican history. As the French audience member begins to recognize and validate Martinican difference, the Caribbean spectator, able to interpret the semiotics of a prologue communicated through the language of Caribbean Carnival tradition, experiences a breaking of the fourth wall, an invitation to participate in the performance of Island Memories, the reinterpretation of history, and renegotiation of the universal.

DOUBLING IN A SECOND LANGUAGE

By cycling between languages and theatrical conventions, Island Memories evokes a marasa consciousness based in the Vodoun sign for the divine twins; unlike Hegelian dialectics, marasa “states the oppositions and invites participation in the formulation of another principle entirely.” [76] The theatrical doubling that is introduced in the prologue sets the stage for further (linguistic) doubling: phrases in Creole. Creole and the Carnival theatrical language of the prologue are the second (oppositional) languages in the context of the production. French and Western theatrical conceits are expected as the means of communication in most theatre settings in both France and Martinique. [77] Césaire’s doubling cycles between Creole and French, Carnival and Western theatre, and thus evokes a lived reality of Martinican women that is both French and Caribbean. The production rewrites French universalism as an ongoing spiral between human universal experience and cultural difference. Telling and acting out stories from their past, singing, dancing from a chair, the actresses relive moments from their personal lives interwoven with references to a larger Martinican collective memory.

I concentrate on Aure’s moments of doubling because I believe they were most likely to accomplish the postcolonial agenda of mobilizing and rewriting the French universal. [78] Because the educated schoolteacher Aure speaks perfect French (in contrast to Hermance, who “reconfigures” French using Creole rules and structures), [79] moments when Aure switches into Creole challenge the spectator’s expectations and thus unmask the limits of French universalism. Whereas Hermance tends to accentuate French lines by using Creole expressions, Aure does not offer the French equivalent when she speaks in Creole. The first instance of linguistic doubling that I would like to observe is a phrase in Creole following a short discussion in French, a supplementary comment at the end of a statement. I will quote the moment of linguistic doubling in Césaire’s text, which matches up more or less with various scripts in the Campagnol’s collection at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, followed by Miller and Makward’s English translation (with Aure’s last line, translated from Creole, shown in italics).

AURE: A ce moment-là je préparais l’Ecole Normale d’institutrices et j’assistais dans sa classe une certaine demoiselle Rosimond. ... Une espèce de mulâtresse qui se coiffait avec deux gros macarons sur les oreilles. C’était cette dame qui toute la sainte journée, faisait chanter à ses élèves: « La neige tombe sur Paris, la neige tombe sur Paris. ... » Eti ou wè la nèj tombé pas isi-ya?

HERMANCE (Elle rit): La neige! [80]

AURE: At that time I was getting ready for the teacher training school exams, and I was helping somebody named Mlle Rosimond with her class. ... A mulatto type who did her hair in two big macaroons over her ears. She was a woman who made her students sing every hour of the blessed day: “Snow’s falling on Paris, snow’s falling on Paris. ...” Ever seen any snow fall around here?

HERMANCE (Laughing): Snow! [81]

Just as the infamous phrase nos ancêtres, les Gaulois (our ancestors, the Gauls) repeated by schoolchildren in African and Caribbean French colonies shows a failure to recognize local culture and realities (deeming every child a descendant of the blond, blue-eyed Gauls), singing “Snow’s falling on Paris” in the Caribbean seems humorously out of context. Aure points out the ridiculous nature of the singing routine, choosing Creole to separate herself linguistically from those who would sing of - and experience - snow falling in Paris. Her choice of Creole unmasks the problematic nature of French universalism. It is interesting to note that Hermance repeats the word snow in French and not in Creole, affirming the place of snow in a French mainland location and cultural context.

French spectators likely got the gist of the joke, perhaps anticipating it (familiar with the complaint about nos ancêtres, les Gaulois), perhaps cued in by laughter, repetition, and likely facetious performance of the word “snow.” However, the doubling serves the vital postcolonial purpose of challenging French universalism, the invisible impediment to the recognition of Caribbean culture. Moreover, Island Memories communicates this criticism to French spectators by forcing them to experience exclusion from the universal, thus unmasking its limitations. Certain French spectators were indeed taken by this moment; two French reviewers for political newspapers note this instance of doubling in their reviews. The leftist newspaper Lutte Ouvrière referred to this moment as one when the actresses “denounce with humor colonial society in which children learn to sing ‘Snow’s falling.’” [82] Likewise, Révolution noted the moment and interpreted it in conjunction with the reference to Christopher Columbus in the prologue, which was the only moment that used French in the somewhat inaccessible prologue. “At school they made us sing ‘snow’s falling on Paris,’ remembers the former schoolmistress, not without smiling. Two lives drawn on the canvas of colonial depths, and it is obviously not for nothing that during the prologue, in costumes that oppose black and white, they make reference to Christopher Columbus and his ships.” [83] Although this reviewer has missed the references to Carnival (the fact that the She-Devils wear black and white because they are companions of Baron Samedi), the author has understood the humor of the situation—and the criticism. As for the Caribbean spectators, I hypothesize that this moment of doubling in Creole reminded them that they are not “almost the same but not quite,” [84] to quote Homi K. Bhabha’s characterization of colonial cultural domination. They are actually more than the same: French and an added Caribbean.

A later example of Aure’s doubling further fine-tunes this critique of the French universal by pointing out the hierarchical levels of access to Frenchness in Martinican society. In this example, doubling serves the purpose of quoting a memory from the past, recounting a statement that was originally made in Creole. The two women are telling the stories of their weddings. Aure, who industriously embroidered on her dress of French cambric herself, enjoyed a glorious wedding day.

AURE: Il y eut une belle cavalcade dans la campagne, le jour de mon mariage. Plus de 20 cavaliers! Moi, même je montais Princesse, ma jument blanche. ... Une belle bête. ... Tous les hommes portaient la veste à queue de morue, comme on dit ici, et le chapeau haut de forme. Il y a eu un grand dîner. Il y avait un mouton, des côtelettes, des crabes farcis, des gâteaux “tourments d’amour” ... tant de bonnes choses. ... Beaucoup de discours, de compliments ... en français naturellement. ... Et voila qu’au beau milieu d’un discours, mon grand-père se lève en disant: «Yo ka palé Francè, man pa ka palé Francè! Au revoir la mariée! » [85]

AURE: We had this wonderful ride in the country the day of my wedding. More than twenty horsemen. I mounted Princess, my white mare ... a beautiful animal! All the men wore what we called a cod-tail jacket and top hats. There was a formal dinner with a whole lamb as well as cutlets, stuffed crabs, coconut pastries ... so many good things. ... A lot of speeches, compliments ... in French, of course. ... And all of a sudden, in the middle of a speech my grandfather gets up and says: “They’re speaking French. I don’t speak French! So goodbye, lady bride!” [86]

Aure, who has worked hard to become the first in her family to pass the competitive French teacher certification exams, enjoys both Martinican cuisine and French customs as part of her perfect sophisticated wedding-day plans. She tells her wedding story, using linguistic doubling to quote her grandfather’s exact words. Sick of sitting through speeches in French, Aure’s grandfather decides to leave. He complains in Creole and then doubly expresses his frustration in French. Although he does not speak French, [87] he repeats the common phrases “Au revoir” and “la mariée,” which serve to mock Aure’s insistence on her French cambric dress, on the horsemen, and, most important, on speaking only French at the reception (“of course”). Aure, who enjoys the French language, refuses to recognize her grandfather’s experience of exclusion: “He could have waited, really! I was so embarrassed.” [88]

This wedding moment creates a linguistic double within a linguistic double: Aure quotes her grandfather, who speaks in Creole, as he doubles into French. He mocks French, calling attention to the validity of Creole as a language of equal status. Likewise, Aure’s grandfather’s experience of exclusion parallels the sentiment of exclusion from the Martinican universal that the French spectator is experiencing. This moment of duplicated linguistic doubling provides a momentary cultural and linguistic role reversal, suggesting the possibility of an inversion of the established ethnosocial pyramid, but it does not assert Creole, the oppositional language, as more valid than French. Rather, it evokes a “marasa trios” [89] - a third option - that cycles between the two languages. This cyclical sign reflects the complexity of the relationship of Martinicans (especially educated mulatto women) to Frenchness. The play itself dramatizes the different advantages that Aure’s linguistic competence, lighter skin, and education have afforded her, especially in terms of her relationships with men. Aure is both the daughter whose mother the halfsisters’ shared father married as well as the one of the two women who did not need to tolerate cheating from her husband. However, the play does not dramatize Aure or her life as more desirable or superior; it is treated as a different example of a French Caribbean woman’s life story. Indeed, the two lives of the women, which seem opposed at the beginning, are united into a Martinican women’s reality by the end of the play. The unification of the halfsisters recalls the Vodoun marasa trios, which allows Césaire to point out, without dwelling on, political difference within a shared history of Martinican women’s memories.

RECEPTION BEYOND THE BINARY

The 1983 performance of Island Memories makes space for a subject to be both French and Caribbean, a marasa trois that cycles between two otherwise mutually exclusive cultural identities (at least within the norms of French society at the time of the production). Le Nouveau Journal commented, “Martinique, Guadeloupe, whichever. French in any case.” [90] Because French society generally did not recognize Martinican cultural difference within Frenchness at the time of this production, communicating this Caribbean - French marasa trios became Césaire’s postcolonial agenda. A reader versed in English-language cultural studies must remember that racial and cultural difference has been ignored in France because it is seen as dangerous, a threat to the spirit of unification. Along those lines, pointing out difference can be seen as a racist or condescending act of relegating a person or artistic work to a limiting particularity. Reviewers of Island Memories, however, made comments that congratulated the team on a successful and respectable communication of a cultural particularity - a nearly impossible feat, according to them, yet one that Césaire accomplished beautifully. They characterized the production as “far from exotic imagery,” [91] “[without] an ounce of folklore,” [92] and “rely[ing] on no artifice.” [93] In dramatizing Martinican women’s reality, Island Memories challenged and rewrote the ideology of universalism that was (and remains) a pervasive characteristic of French society.

In rewriting this universal - different binary and empowering Caribbeans to continually rewrite their own histories and relationships to Frenchness, Island Memories transcends the victim–perpetrator binary as well. The horrors of the past are pointed out and accepted in order to move forward into the next stage. As Césaire explains:

It is about accepting our past, it is not about being embarrassed, it is no longer about crying over it. We have acquired the right to no longer cry over our past, we must take responsibility for it and be able to move past it. To refer to our past is to show today our power to accept it despite the instability of our history. The simple fact that these women have survived, the courage, strength, as well as the desire to encourage their children to move forward is, for me, part of a life force that takes on liberating facets. [94]

Césaire also accepts the absence of a clearly written and politically satisfying history and the inherent ambiguities and contradictions of lived memory. Judith Miller has argued that through madness (but not melancholia), French Caribbean women playwrights “show a culture whose vibrant spirituality has allowed women and men to work through and conquer a multitude of psychic horrors.” [95] An important scene for Miller’s argument is the mimed “archetypal rape scene” of Aure’s grandmother by the white slave master, which Césaire specifies in her text as the “only time the slavery era is recalled.” [96] The memory is deliberately blurred: “We can hear the creaking of a bed across which a body has thrown itself. Malvina [Aure’s grandmother] stands up slowly and leans over the bed. She raises her arm; is it a gesture of love or aggression?” [97] The unanswered question represents an acceptance of the limitations and difficulties of the memory of slavery. Gilbert and Tompkins claim that “women’s bodies often function in postcolonial theatre as the spaces on and through which larger territorial or cultural battles are being fought.” [98] In blurring the gesture, Césaire introduces the possibility of agency as opposed to rape, and her deliberate ambiguity cycles between the two. She thus recognizes the accusation that women have been complicit in French cultural supremacy with realistic acceptance. In so doing, she allows for and encourages mediation between French Caribbean women and men, whose different responses to colonialism have resulted in a cultural gap. Through this cycle, Césaire refuses to relegate women to the sole position of the victim.

The Caribbean spectator is likewise not confined to the victim role, and the French spectator is not confined to the role of the perpetrator. The Caribbean spectators can begin to accept and move past their difficult and ambiguous memories, while French spectators can express empathy without feeling personally responsible for the histories of slavery and colonialism. A reviewer for a Parisian and (not coincidentally) Christian journal commented, “It is not about crying, pitying oneself, complaining, asking for pity. It is only about ‘saying.’” [99]

CONCLUSION

Through the technique of doubling in a second language and a juxtaposition of the two half-sister protagonists of Island Memories, Ina Césaire evokes a marasa consciousness that cycles between dialectical categories of identity (French - Caribbean, colonizer - colonized, white - black, man - woman, and victim–perpetrator). Moreover, Island Memories cycles between the notions of the human universal and cultural difference, thus rewriting French universalism - a system that pervades French society on all levels - as a marasa trios, a third option, that is encapsulated by the lived memories of Martinican women. The major postcolonial agenda of the play thus becomes the rewriting of the French universal, which is replaced with an act of cycling between “Martinican women’s theatre” and “theatre.” This postcolonial agenda is specific to the cultural politics of Martinique and Guadeloupe and to the particular situation of women on these islands. My analysis thus provides a salient example of how theoretical frameworks for interpreting postcolonial theatre are influenced by local cultural discourse that exists in the context of a production and that controls cultural politics as well as possible strategies for recognition and resistance.

Although the concept of the universal has been disparaged by English language scholars of postcolonial theatre, it is a vital tool for French Caribbean women’s theatre in that it allows artists to rewrite Martinican and Guadeloupean history and the ongoing departmental relationship to France, as well as to bridge the gap that has formed between Caribbean women and men in the aftermath of colonialism, a sexualized system of domination. Ina Césaire’s restorative, postcolonial agenda uses Carnival and the Creole language to unmask the problem of French universalism and rewrites the traumatic memories of Martinican women, uniting spectators and participants in a particular – universal marasa trois.

Emily Sahakian [Top]

Emily Sahakian is a doctoral candidate in Northwestern University’s Interdisciplinary Ph.D. in Theatre and Drama (IPTD), working on a dual Ph.D. with the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales. She completed a Maîtrise degree in 2004 at the Sorbonne Nouvelle, where she wrote her master’s thesis on French Caribbean women’s theatre. Examining Martinican and Guadeloupean women’s plays at the Ubu Repertory Theater in New York, her dissertation investigates theatre as a cultural translation of traumatic memory.

Research for this essay was made possible by several grants from Northwestern University: the French Interdisciplinary Group Travel Grant, the Program in African American History Travel Grant, and the Paris Program in Critical Theory Fellowship. I would like to express my gratitude to Christiane Makward, who provided valuable feedback as well as the production images from her personal collection, and to Sandra Richards, whose insightful comments helped me develop my argument. I would also like to thank two anonymous readers for their helpful comments and Catherine Cole and Leo Cabranes-Grant, whose generous editorial support guided me greatly as I shaped the final version of this essay.

ENDNOTES:

[1]

See Alvina Ruprecht, ed., Les Théâtres francophones et créolophones de la Caraïbes (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2003); Carole Edwards, Les Dramaturges antillaises, (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2008); Christiane Makward, “De bouche à oreille à bouche: Ethno-dramaturgie d’Ina Césaire,” in L’Héritage de Caliban, ed. Maryse Condé (Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe: Éditions Jasor, 1992), 133–46; Makward, “Reading Maryse Condé’s Theatre,” Callaloo 18.3 (1995): 681–9; Makward, “Pressentir l’autre: Gerty Dambury, dramaturge poétique guadeloupéenne,” L’Annuaire Théâtral 28 (2000): 73–87; Melissa L. McKay, Maryse Condé et le théâtre antillais (New York: Peter Lang, 2002); Suzanne Rinne and Joëlle Vitiello, eds., Elles écrivent des Antilles: Haïti, Guadeloupe, Martinique (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1997).

[2]

VèVè Clark, “Developing Diaspora Literacy and Marasa Consciousness,” in Comparative American Identities: Race, Sex, and Nationality in the Modern Text, ed. Hortense J. Spillers (New York: Routledge, 1991), 40–57.

[3]

Christopher B. Balme, Decolonizing the Stage: Theatrical Syncretism and Post-Colonial Drama (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999); Helen Gilbert and Joanne Tompkins, Post-Colonial Drama: Theory, Practice, Politics (London: Routledge, 1996).

[4]

Suzanne Houyoux, “Un Entretien avec Ina Césaire Fort-de-France, Martinique, 5 Juin 1990,” in ,em>Elles écrivent des Antilles, ed. Rinne and Vitiello, 349–57, at 353.

[5]

Makward, “De bouche à oreille à bouche,” 134.

[6]

While the word “mulatto” is somewhat out of fashion in the United States, it is still common n Martinique, where it signifies a specific class of people: the progeny of the mixed-race recognized hildren of plantation owners.

[7]

See Makward and Miller in their translation Island Memories of Ina Césaire’s play Mémoires d’Isles in Plays by French and Francophone Women: A Critical Anthology, ed. and trans. Christiane P. Makward and Judith G. Miller (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 49–74, at 56 n. 8.

[8]

Ibid., 61–2.

[9]

9. See ibid., 62 n. 9.

[10]

10. Ibid., 47.

[11]

Suzanne Crosta, “De la communication politique à la recherché d’un espace-écoute: recettes thérapeutiques dans le théâtre antillais,” in Les Théâtres francophones et créolophones, ed. Ruprecht, 59–72.

[12]

Bridget Jones, “Two Plays by Ina Césaire: Mémoires d’Isles and L’Enfant des passages,” Theatre Research International 15.3 (1990): 223–33, at 228.

[13]

Ibid.

[14]

See Richard D. E. Burton and F. Reno, eds., French and West Indian: Martinique, Guadeloupe, and French Guiana Today (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1995).

[15]

David Beriss, Black Skins, French Voices: Caribbean Ethnicity and Activism in Urban France (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2004), 25.

[16]

See Didier Fassin and Éric Fassin, De la question sociale à la question raciale (Paris: La Découverte, 2006).

[17]

See Edouard Glissant’s discussion of sameness and diversity in Caribbean Discourse: Selected Essays, trans. J.Michael Dash (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1989), 97–104; or Richard D. E. Burton’s characterization of the three great French Caribbean literary movements (Aimé Césaire’s négritude, the Créolité movement, and Glissant’s theories of diversity and relation) as “three principals of difference” in “The Idea of Difference in Contemporary French West Indian Thought: Négritude, Antillanité, Créolité,” in French and West Indian, ed. Burton and Reno, 137–66, at 141.

[18]

Jean Bernabé, Patrick Chamoiseau, and Raphaël Confiant, Eloge de la Créolité/In Praise of Creoleness, trans. Mohamed B. Taleb-Khyar (Paris: Gallimard, 1993), 87.

[19]

Beriss, 38.

[20]

Éric Fassin, “‘Good to Think’: The American Reference in French Discourses of Immigration and Ethnicity,” in Multicultural Questions, ed. Christian Joppke and Steven Lukes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 224–41.

[21]

A. James Arnold, “The Gendering of Créolité: The Erotics of Colonialism,” in Penser la créolité, ed. Maryse Condé and Madeleine Cottenet-Hage (Paris: Karthala, 1995), 21–40.

[22]

Ellen M. Schnepel, “The Other Tongue, the Other Voice: Language and Gender in the French Caribbean,” in Language and Social Identity, ed. Richard K. Blot (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2003), 199–224.

[23]

Ibid., 210.

[24]

See Makward, “De bouche à oreille à bouche”; and Christiane Makward, “Filles du soleil noir: sur deux pièces d’Ina Césaire et de Michèle Césaire,” in Elles écrivent des Antilles, ed. Rinne and Vitiello, 335–47.

[25]

Glissant, Caribbean Discourse, 196.

[26]

Bridget Jones, “Theatre and Resistance? An Introduction to Some French Caribbean Plays,” in An Introduction to Caribbean Francophone Writing: Guadeloupe and Martinique, ed. Sam Haigh (Oxford: Berg, 1999), 83–100, at 83.

[27]

Jones, “Two Plays by Ina Césaire,” 231.

[28]

Alvina Ruprecht, “Les Pratiques scéniques et textuelles de la région caribéenne francophone et créolophone: Mise au point,” in Les Théâtres francophones et créolophones, ed. Ruprecht, 11–34, at 26.

[29]

Ibid., 18.

[30]

Aurélie Dalmat, interview with the author, 15 July 2005, Fort-de-France, Martinique.

[31]

Margaret A. Majumdar, Postcoloniality: The French Dimension (New York: Berghahn Books, 2007).

[32]

Gilbert and Tompkins, 2.

[33]

Ibid., 3.

[34]

Ibid., 257.

[35]

“On n’en est plus au niveau de ‘Qui sommes-nous?’ ... ‘Quelle est notre identité?’ ’identité, elle est. Moi, personnellement je ne me pose plus la question de l’identité, je la ressens très profondément, sans complexe, sans amertume. ... On ne peut pas assimiler cela! Quand je lis Dostoîevsky je ne suis pas Russe, or je peux entrer dans la peau des personnages et Les Frères Karamazov, ça me passionne! J’aime Tchekov! Donc je crois que n’importe qui peut comprendre l’âme d’un Antillais s’il prend la peine de (se) pénétrer lui-même.” Christiane Makward and Adam John, “Faire son théâtre en Martinique: Ina Césaire et Michèle Césaire,” Oeuvres et Critiques 26.1 (2001): 110–21, at 116. [This and any other translations otherwise unattributed are my own.]

[36]

See Patrice Pavis, “Introduction: Towards a Theory of Interculturalism in Theatre?” in em>The Intercultural Performance Reader, ed. Patrice Pavis (London: Routledge, 1996), 1–21.

[37]

Gilbert and Tompkins, 9.

[38]

Rustom Bharucha, “Peter Brook’s Mahabharata: A View from India,” in Theatre and the World: Essays on Performance and the Politics of Culture, ed. Bharucha (London: Routledge, 1993), 68–87, at 70. [Also in Peter Brook and the Mahabharata: Critical Perspectives, ed. David Williams (London: Routledge, 1991), 228–52.]

[39]

Ibid., 84.

[40]

Peter Brook, “The Culture of Links,” in Intercultural Performance Reader, ed. Pavis, 63–6.

[41]

Gilbert and Tompkins, 10.

[42]

Balme, Decolonizing the Stage, 11, 17.

[43]

Ibid., 271–2.

[44]

Maryse Condé, An tan revolisyon: Elle court, elle court la liberté. Pointe-à-Pitre: Conseil Régional de la Guadeloupe, 1989; Maryse Condé, with Doris Y. Kadish,and Jean-Pierre Joseph Piriou, In the Time of the Revolution. (Electronic Edition) by Alexander Street Press, L.L.C., Alexandria, VA 2009. Maryse Condé, Doris Y. Kadish, and Jean-Pierre Joseph Piriou, 1989. Available at: http://solomon.bld2.alexanderstreet.com.turing.library.northwestern.edu/cgi-bin/asp/philo/navigate.pl?bld2.928.

[45]

See Makward, “Reading Maryse Condé’s Theatre,” 686.

[46]

“Je me suis inspirée de l’occasion de sortir l’ethnologie de son ghetto de specialists et de le restituer à ceux qui sont les premiers concernés”; Césaire quoted in Ruben Gachy, “Les mémoires d’Isles: Maman N et maman F,” POCO (October 1983): 32–3.

[47]

Quotations are most often taken from Christiane Makward and Judith Miller’s published text, which was written after the production. At the Département des Arts du spectacle at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris [hereafter BnF], I consulted the archival collection on the Théâtre du Campagnol, which houses various performance scripts that I compared with the published text, as well as production reviews.

[48]

“Pointillieux, on l’imagine, sur les plans politique, linguistique, et cutané.” Makward, “De bouche à oreille à bouche,” 138.

[49]

“Libéral sans doute, mais modeste, mal informé des réalités antillaises et éventuellement, à la fibre patriotique sensible.” Ibid.

[50]

Bridget Jones notes that the “judicious” use of Creole “prove[s] no obstacle to varied audiences,” arguing that theatre is a place where “barriers of verbal incomprehension [can] be overcome.” Jones, “Two Plays by Ina Césaire,” 228, 231. Stéphanie Bérard makes a similar claim, pointing out that Césaire’s Hermance uses Creole mostly to rephrase claims already made in French. Bérard, “Creole ou/et Français: le multilinguisme dans Mémoires d’Isles d’Ina Césaire,” Glottopol 3 (January 2004): 122–30, at 123.

[51]

Aimé Césaire: Une Tempête (Paris: Seuil, 1969); La Tragédie du Roi Christophe (Paris: Présence Africaine, 1970); Une Saison au Congo (Paris: Seuil, 1967).

[52]

See Christopher Balme’s theorization of the semiotics of postcolonial drama; Balme, “Syncretic Theatre: The Semiotics of Postcolonial Drama and Wole Soyinka’s Death and the King’s Horseman,” in New Theatre in Francophone and Anglophone Africa, ed. Anne Fuchs (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1999), 209–28, at 227.

[53]

Gerard Aching, Masking and Power: Carnival and Popular Culture in the Caribbean (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002), 6.

[54]

Gilbert and Tompkins (172) make this conclusion for a very similar case study, Jack Davis’s The Dreamers.

[55]

Césaire, Island Memories, 52.

[56]

See Edouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997).

[57]

Edouard Glissant, “The Unforeseeable Diversity of the World,” trans. Haun Saussy, in Beyond Dichotomies: Histories, Identities, Cultures, and the Challenge of Globalization, ed. Elisabeth Mudimbe-Boyi (Albany: State University of New York, 2002), 287–95, at 290.

[58]

Jones, “Two Plays by Ina Césaire,” 226.

[59]

Penchenat quoted in Mireille Lespinasse, “Les Violons du Bal,” Avant Scène, consulted at Département des Arts du spectacle, BnF.

[60]

Makward, “De bouche à oreille à bouche,” 134.

[61]

“La mémoire des peuples et de cultures.” Césaire quoted in Gachy, 32.

[62]

Jones, “Two Plays by Ina Césaire,” 225–6.

[63]

“A cela s’ajoute le jeu des comédiennes qui sont elles-même antillaises, et qui m’ont aidée en apportant leurs vécus, leurs souvenirs, enrichissant le texte, elles ont retrouvé des gestes naturellement, la recherché a été dépassée par la vie, et aussi la mise en scène de Jean-Claude Penchenat qui connaît, il est vrai, très peu les Antilles.” Césaire quoted in Gachy, 33.

[64]

“Le mécanisme de la mémoire, quelque chose qui m’est cher!”; Penchenat quoted in Lespinasse.

[65]

Césaire, Island Memories, 49. This author’s note appears both in the program for the performance (archived in the Département des Arts du spectacle, BnF) and in the published text.

[66]

Taken from the program insert; consulted at Département des Arts du spectacle, BnF. Cf. quotation in n. 46.

[67]

Judith Miller, “Caribbean Women Playwrights: Madness, Memory, but Not Melancholia,” Theatre Research International 23.3 (1998): 225–32, at 225.

[68]

Makward, “Filles du soleil noir,” 337.

[69]

Césaire, Island Memories, 52.

[70]

For a discussion of Carnival in the production, see Pascale De Souza, “Discours carnavalesque chez Ina Césaire: déferler les Mémoires d’Iles,” Oeuvres et Critiques 26.1 (2001): 122–33.

[71]

“Inverser symboliquement la pyramide ethno-sociale.” Ibid., 128.

[72]

“Qui n’a pas vu un carnaval antillais ne sait pas ce qu’est un carnaval. Je ne parle pas, comme à Rio de débauche d’argent. Les gens se transforment, il y un jour ou` tous les hommes sont femmes et ou` les femmes sont hommes, les sexes s’inversent et les pauvres deviennent riches ... c’est le goût du masque primaire, on prend ce qu’on a à la maison. Le visage peint, on ne reconnaît personne, c’est un moment différent, délirant.” Césaire interviewed in Houyoux, 355.

[73]

See Christopher Balme’s discussion of Carnival in Caribbean theatre; Balme, Decolonizing the Stage, 44–53. Note especially Maxwell’s belief that while Caribbean artists were divided between “folk” and “Western-influenced” groups, Carnival could provide healing through a synthesis of this rupture; ibid., 52.

[74]

Gilbert and Tompkins, 231.

[75]

Aching, 7.

[76]

Clark, 43.

[77]

Although there are strong traditions of comedic skits in Creole and contes, or folktales, “theatre” in Martinique comes out of the French tradition.

[78]

Although the playscripts in the archival collection of the Théâtre du Campagnol in the BnF’s Département des Arts du spectacle are not exactly the same as the published text and notably include moments of improvisation, the overall arc of the play as well as the dialogue in each are very similar. The dialogue I quote in this article appears in both places.

[79]

See the juxtaposition of these two women’s use of language in Bérard, 125.

[80]

Ina Césaire, Mémoires d’Isles: Maman N. et Maman F. (Paris: Éditions Caribéennes, 1985), 40–1.

[81]

Césaire, Island Memories, 54.

[82]

“Dénoncent avec humour la société coloniale dans laquelle les enfants apprennent à chanter ‘Tombe la neige.’” P. M., “‘Mémoires d’Iles, Maman N. et Maman F.’ par le Théâtre du Campagnol,” Lutte Ouvrière 816 (21 January 1984), consulted at the Département des Arts du spectacle, BnF.

[83]

“‘A l’école on nous faisait chanter la neige tombe sur Paris,’ se souvient non sans sourire l’ancienne institutrice. Deux vies dessinées sur toile de fond colonial et ce n’est évidemment pas pour rien qu’au prologue, dans ces costumes ou` s’opposent le noir et le blanc, on évoque Christophe Colomb et ses caravelles.” “Mémoires d’Isles ‘Maman N et Maman F,’” Révolution (20 January 1984), consulted at the Département des Arts du spectacle, BnF.

[84]

Homi K. Bhabha, The Location of Culture (New York: Routledge, 1992), 86.

[85]

Césaire, Mémoires d’Isles, 71–2.

[86]

Césaire, Island Memories, 68.

[87]

Bérard (129) suggests a second reading: although it is likely that someone from his generation would not speak French, it is also possible that Aure’s grandfather knows French but refuses to speak it out of pride.

[88]

Césaire, Island Memories, 68.

[89]

A reference to the divine twins and the child born directly afterward, a sign of the marasa consciousness that moves beyond the binary in a cyclical, spiral relationship. Clark, 43.

[90]

“La Martinique, la Guadeloupe, qu’importe. Françaises en tout cas”; J. M., “Maman N et Maman F: Mémoire des Antilles,” Le Nouveau Journal (14 January 1984). Note that this review is a response to a reprise of the same production at Théâtre 18 in 1984.

[91]

“Loin des imageries exotiques”; ibid.

[92]

“Il n’y a pas une once de folklore”; ibid.

[93]

“N’a eu recours à aucun artifice”; C. Ba., “Mémoires d’Isles par le Campagnol,” Le Monde (17 January 1984).

[94]

“Il s’agit d’accepter notre passé, il ne s’agit pas d’en avoir honte, il ne s’agit plus d’en pleurer. Nous avons acquis le droit de ne plus pleurer sur notre passé, nous devons l’assume et pouvoir le dépasser. Se référer à notre passé, c’est montrer aujourd’hui notre pouvoir de l’assumer, malgré les vicissitudes de notre histoire. Le simple fait que ces femmes aient survécu, le courage, la force, ainsi que leur désire de faire progresser leurs enfants, pour moi fait partie d’un élan de vie qui prend des aspects libératoires.” Césaire quoted in Gachy, 33.

[95]

Miller, 225.

[96]

Césaire, Island Memories, 59.

[97]

Ibid., 58–9.

[98]

Gilbert and Tompkins, 215.

[99]

“Il ne s’agit pas de pleurer, de s’apitoyer, de se faire plaindre, d’invoquer la pitié. Il s’agit seulement de ‘dire’”; D. M., “Rue Cases—Nègres sur scène,” Témoignage Chrétien, undated newspaper clipping from the Département des Arts du spectacle, BnF.

|