PIERRE BERTON, JOURNALIST, historian, and celebrity – was the best known Canadian of his day; a man, born in the North and educated on the West Coast, who conquered every medium of communication in Central Canada: newspapers, magazines, books, radio, and television. By the time of his death he had become, in a phrase often used to describe him, “a Canadian icon.” It was a phrase he liked to mock, but also one he readily accepted. He was proud of his accomplishments, and he had good grounds to be.

This life fascinated me as a biographer and historian. Pierre Berton lived for eighty-four years, and for more than half a century he was very likely the most active Canadian of his generation. When I decided to tackle his biography early in the new century, I did so in part to reacquaint Canadians with the full range of Berton’s life and career. My sense was that the most important stages of that career had come to be displaced in public memory by Berton’s great success as a best-selling author of popular Canadian history.

Homage to the R-34 (1967-68) detail.

Enamel paint on plywood and steel, 2.95 x 31.54 x .025 m overall, National Gallery of Canada. ©The Estate of Greg Curnoe

To trace the trajectory of this variegated life would also provide a means of exploring several contours of social and cultural transformation in Canada during the twentieth century, from the earliest years of radio to the first decades of the World Wide Web. Berton was above all a communicator, so a major focus of the biography would be on forms of communication – especially that of the book. I wanted to dwell on the ways meaning comes to be attached to an author and his books. To explore this path, I needed to devote attention not simply to Berton’s life but to his ideas and themes, and the contents of his writings; to the way they came to be received by readers and critics, and the role they played in the generation of cultural meaning. In the context of cultural meaning and resonance, the critical reception of a book can be at least as revealing as the book itself.

Before the icon comes the brand. To become an iconic cultural brand a product must not only achieve success in the marketplace but also gain cultural resonance. Many products become brands, but few brands become iconic. The product called “Pierre Berton” became both. But how?

I

During the course of research on what became Pierre Berton: A Biography (2008), I encountered different types of branding theory, of which four proved helpful. The first, mind-share, links a brand’s characteristics to basic concepts in a consumer’s mind and then stakes out a particular claim for association and pushes it. The second, emotional – is an extension of mind share, with emphasis on the way associations are communicated – emotional appeals and emotional relationships with core customers. The third is viral, with its emphasis on factors leading to creation of brands, especially the role of consumers in ‘discovering’ a brand for themselves. Then, through word of mouth and other means of communication, the Good News spreads like a virus. The subject of Malcolm Gladwell’s influential book The Tipping Point; How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference (2000), viral branding seemed especially insightful where Berton was concerned, for it helped explain the extraordinarily quick rise of his reputation in the last few years of the 1950s. In 1957 he was mainly known as a well-regarded and opinionated regional journalist. In 1959 he had become a national phenomenon and a ubiquitous public presence.

Yet while viral branding helps explain the circulation of information and interest associated with Berton’s rise, it does not directly address the development of meaning. That is, it does not explain how and why Berton’s name and works came to mean so much to so many people. A theory of cultural branding seemed necessary, and I discovered one in Douglas B. Holt’s book, How Brands Become Icons: The Principles of Cultural Branding (2004). In Holt’s view, a cultural brand comes into existence when meaning becomes attached to it as various ‘authors’ (in the postmodern sense) tell stories involving the brand. In the case where the brand is a writer, these ‘authors’ take several forms apart from the writer himself – as publishers, critics, reviewers, and readers.

The brand stories such ‘authors’ tell (so goes Holt’s theory) intersect with everyday life, allowing the brand to connect with cultural and society in the creation of meaning. These stories take several forms, use metaphor and symbols, and circulate within society, shaping forms of collective understanding. “A brand emerges when these collective understandings become firmly established,” Holt writes. In this way, and in order to become a cultural brand, a product comes to acquire an identity value social and cultural in nature. As Holt notes: “Consumers flock to brands that embody the ideals they admire, brands that help them express who they want to be. The most successful of these brands become iconic brands.”

Cultural brands address societal contradictions: “We experience our identities – our self-understanding and aspirations – as intensely personal quests,” Holt writes; and these “desires and anxieties linked to identity are widely shared across a large fraction of a nation’s citizens.” In order to become iconic, a cultural brand must “perform” and, in doing so, extend certain “Identity Myths” that address these desires and anxieties. These identity myths, Holt tells us, “are useful fabrications that stitch back together otherwise damaging tears in the cultural fabric of the nation. In their everyday lives, people experience these tears as personal anxieties. Myths smooth over these tensions, helping people create purpose in their lives and cement their desired identity in place when it is under stress.” Over time, Holt concludes, an association comes to exist between the brand’s identity myth and the brand itself.

In the case of Berton, over the decades his name gained symbolic meaning and cultural resonance. The identity myth and the author became one. The cultural brand became an iconic brand.

II

In 1947, Pierre Berton left a fledgling newspaper career in Vancouver to move to Toronto. His sensational series of articles on “Headless Valley,” written for the Vancouver Sun, had made headlines around the world and drew the attention of Arthur Irwin, the editor of Maclean’s magazine, Canada’s equivalent to Time.

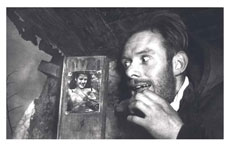

Pierre Berton discovers Rita Hayworth pin-up photo in trapper’s cabin during 1947 “Headless Valley” adventure. William Ready Division, McMaster University Library

Within a decade he was the magazine’s managing editor, having by then written about a hundred articles for the magazine on a wide range of subjects: the internment of Japanese Canadians during the war; anti-semitism in the workplace; profiles of business moguls, Toronto street gangs, and Canadian troops in Korea; accounts of his northern origins. Berton began to appear regularly on CBC radio, often talking about the Canadian North and therefore about himself. His first book, The Royal Family (1954) appeared under the Knopf imprint, but overexposure of the monarchy during the months leading to the coronation of Queen Elizabeth kept sales modest. The book, as much cultural anthropology as group biography, managed to annoy both those who disliked and admired the Royals. It provided a spirited history of British royalty, while treating British monarchs as if they were an Amazon tribe and adopting a bemused and ironic tone that at times rivaled that of Lytton Strachey, although good-humoured.

But the book did nothing to advance Berton’s name toward the status as a brand. He had little use for the monarchy, and monarchical attachment was in general on the wane in Canadian public life. Today, The Royal Family can be seen as an inadvertent case study of how not to write a book that promotes brand creation.

Things changed with the appearance of The Mysterious North in 1956 and Klondike two years later. The former was a book that said little about fur traders and native peoples; instead it was about the rugged New North of industrial expansion in the 1950s. As author, he infused the book with the impeccable credential of an almost mythic Canadian pedigree – a man of the territorial north, but, like most Canadians, one who lived in the south. In this way, Berton could at once play into the comforting myth of “the true north strong and free,” allowing readers to differentiate themselves from Americans, while assigning the north a new relevance as a largely undiscovered land of mineral wealth and industrial materials. Publication of The Mysterious North in 1956 coincided with St. Laurent administration’s discovery of northern economic potential, anticipating and perhaps helping shape Diefenbaker’s “northern vision,” intent on exploiting this new north and linking it to a distinct Canadian identity.

More important, the book addressed tensions of identity in a way that aimed at reconciliation – acknowledging the idea of Canada as a northern nation while linking its future to the industrial south; easing the discrepancy between the ruggedness of northerners and the soft life of southerners. In this way, a link came to be forged between Berton the author and notions of national vision, national policy, and national destiny. The Mysterious North became a best-seller and won Berton his first Governor General’s Award.

Klondike appeared in 1958, the sixtieth anniversary of the Klondike gold rush and with the success of The Mysterious North still fresh. It was a book that Berton, born in the North and the son of a man in search of Klondike gold in 1898, was born to write. It, too, carried with it a contemporary lesson, one that transcended the story of the gold rush. The book argued colourfully that an earlier generation of Canadians, in their quest for worldly success, had forged a future and, in doing so, discovered themselves. The Mysterious North gave confidence to the rather timorous Canadians of the 1950s as they confronted the challenges of the New North. It showed them that they were not simply cautious and nice; they were also capable of heroic adventure and risk taking. It fixed and froze the identification of Berton as the voice and chronicler of the North in the public mind; and it won Pierre Berton his second Governor General’s Award.

III

In 1958, Berton reinvented himself, as he had in 1947 when he left Vancouver as a first-rung reporter to write in Ontario for Canada’s leading magazine. Now he left Maclean’s to write a daily general interest column for Canada’s leading daily, the Toronto Star. He had already become a regular panelist on the CBC’s new TV quiz show, “Front Page Challenge,” and this – together with renown as author of two award-winning books – had given him national exposure. The column was called, simply, “By Pierre Berton.”

His name was becoming as important as his subject matter.

Beginning in September, 1958, and continuing for the next four years, he wrote 1200 words a day, five days a week. (Those of today’s columnists, such as James Travers or Rick Salutin, which appear once or twice weekly, are significantly shorter.) “By Pierre Berton” became what Salutin and others, such as Robert Fulford, came to regard as the best general column in Canadian newspaper history. Salutin’s writing career, in fact, began when he stumbled upon Berton’s daily presence in the Star as a high school student.

The column was hugely influential, covering a vast range of topics. Berton’s rule of thumb for the column was, as he put it, to make readers “wonder what the sonofabitch was going to do next.” He exposed municipal corruption in Vaughan, leading to a commission of inquiry, the resignation of several aldermen, and the jailing of another. He shared his favourite home recipes. He reveled in nostalgia and wrote often on popular culture, such as the golden age of radio.

But two subjects tended to dominate the thousand columns he wrote during his tenure at the Star: consumerism and social justice. He revealed the hard sell tactics of the funeral industry (before Jessica Mitford did so in her best-selling book The American Way of Death) and the Arthur Murray Dance Studio – in his view, rackets that took advantage, respectively, of the guilt and the insecurity of vulnerable people. His consumer columns, which embraced consumption but warned against hucksters and con men, intuitively addressed social tensions – tensions of an increasing urban nation embracing the culture of consumption but wary of the plethora of untested products. On social justice, Berton’s column railed against capital punishment and exposed and condemned racial discrimination and anti-semitism. It became the leading voice in Canada urging a compassionate, equitable, and just society. To cite but one example, it was Berton’s October 5, 1959, column “Requiem for a Fourteen Year Old,” written in the immediate aftermath of an Ontario court’s verdict of death by hanging in the murder trial of Steven Truscott, that galvanized the debate over capital punishment. The column took the form of a poem. Its final stanza ended much as the first had begun, in the white heat of anger:

In Goderich town

The trees turn red

The limbs go bare

As their leaves are bled

And the days tick by

As the sky turns lead

For the small, scared boy

On the small, stark bed

A fourteen-year-old

Who is not quite dead.

One of the many readers of the column that day was Isabel LeBourdais, Toronto journalist and mother of a fourteen-year-old son. She decided to investigate the conduct and evidence of the trial, did so doggedly, and in 1965 published her book, The Trial of Steven Truscott, acknowledging her indebtedness to Pierre Berton and reproducing “Requiem for a Fourteen Year Old” in full. Thus began the half-century-long quest for Truscott’s exoneration, a quest that continued until August 2007, when another court declared Truscott’s conviction a miscarriage of justice – almost three years after Pierre Berton’s death.

IV

Having had success with The Mysterious North and Klondike, Jack McClelland proved eager to profit by Pierre Berton’s name. During Berton’s Star years, author and publisher gathered together his columns regularly and published them in book form, often against the advice of literary-minded editors: Just Add Water and Stir (1959); Adventures of a Columnist (1960); Fast Fast Fast Relief (1962); The Big Sell (1963). The dust jacket of Adventures of a Columnist displayed visually the reality of Berton as incipient brand. Dominated by text rather than image, the book’s title was in a script that appeared handwritten above the author’s name. That name occupied the bottom three-quarters of the cover and was in such large type that B E R spanned the full width of the cover, forcing T O N below it. Frank Newfeld’s design, the first of many for Berton books, gave the impression that this was not merely the name of an author but an abstraction, an important entity unto itself.

A review of Just Add Water and Stir by critic Arnold Edinborough in Saturday Night provides a textbook example of brand-building endorsement as it applies to Berton: First came the idea of a man larger than life both figuratively and literally (“Pierre Berton is a giant in the newspaper industry – he stands well over six feet”); second, emphasis on his extraordinary productivity (“He turns out more wordage in a day than most people do in a week”); third, acknowledgement of authority, benign and benevolent (“This undoubted eminence sometimes leads him to sound a little like God, but he still manages … to please all comers”); fourth, provision of some general criticism, turning this awesome deity into the flawed hero of the coffee shop (“His intemperate recipes for Tomato Soup, Baked Beans, Corn Beef Hash, and Clam Chowder … betray a gluttonous and greedy gourmand, rather than a gourmet”).

Finally came reinforcement of the original “larger than life” motif, but now – with attention drawn to the man’s background and his abundant talent and accomplishments – a motif given full-blooded resonance through the link of obligation made between the man and those who “bought” him.

“Berton,” Edinborough wrote, “is still the best newspaper columnist in the country and his collected columns should be studied by every journalism student. They show what true journalism should be – probing, factual, tightly written, sometimes jolting and always interesting.”

Notices like Edinborough’s – and there were hundreds over the decades – were a marketer’s dream, for they were meaning-makers, not simply reviews. They assessed the content of Pierre Berton’s articles, columns, books, and television programs, but they also forged links between Berton’s beliefs and those of his readers and viewers. In doing so, they became instrumental in transforming Berton from a familiar surname into an enduring brand.

What had come to really matter was Berton himself, regardless of what he might write, for the name resonated with attendant meaning: child of the north; wunderkind newspaperman straight out of Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s popular 1920s play The Front Page, populated by hard-drinking newshounds intent on the scoop, and portrayed on the screen in the thirties and forties in any number of Hollywood movies. To these attributes had now been added certain moral qualities. The public also knew Berton as a leading crusading consumer and social justice advocate, one who reflected the kind of just and equitable society Canadians desired, but did not yet have. Canada as Canadians wanted it to be. Berton’s Canada. All this added lustre and resonance to the brand.

Two other Berton books of the Sixties, The Comfortable Pew (1965) and The Smug Minority (1968), further entrenched the brand. Both volumes were in themselves iconic, and both were written at the request of important social groups. In both cases, Berton captured the zeitgeist, as would most of his later books. He wrote The Comfortable Pew at the request of the Anglican Church, but he addressed the Christian church in general. The Comfortable Pew questioned the contemporary Church’s relevance and attacked the complacence of churchgoers. It pointed out their lack of connection to the baby boom generation and noted the Generation Gap that now existed. Remembered years later as an attack on mainstream religious observance, it is better viewed as one of the few books written in the sixties in Canada on the question of generational alienation. Here was yet another refraction of the Berton image, one with which another generation could identify: Pierre Berton, champion of the culture of youth.

Two years later, in 1967, the federal NDP asked Berton to do for the cause of poverty and class what The Smug Minority had done for the cause of religious values. Published in January 1968, the book hit stores in the months before the 1968 federal election. It was, in effect, a popular and accessible companion to John Porter’s now classic study, The Vertical Mosaic: An Analysis of Social Class and Power in Canada, which had appeared three years earlier. Berton’s primer addressed tensions related to secularization, the need for relevant social values, the alienation of youth, the existence of poverty and inequality. In doing so, The Smug Minority further cemented his image as compassionate Canadian, thereby playing into the sustaining identity myth of Canadians as an empathetic and caring people, but with institutions that failed too often to address those values. Little wonder, then, that the Sixties Generation would soon buy his books in droves and continue to do so for decades.

The Comfortable Pew sold 175,000 copies and The Smug Minority in the region of 100,000, in part because the NDP used it extensively during the election campaign. In this respect, The Smug Minority was a catalyst of Trudeau’s “Just Society.” With the publication of these two very successful polemical works we are close to the point at which, to many observers, Berton the cultural brand came into existence: that is, with the appearance of The National Dream and The Last Spike in 1970 and 1971, respectively. My view is that by 1970 the elements requisite to formation of the brand were already fully fleshed out and on display, ready to be enriched and entrenched.

Recall this: All successful cultural brands make an emotional connection with their core customers, but an iconic brand does so at the level of social myth. A brand becomes iconic when the myth-like narratives associated with it come to address fault-lines in the cultural fabric of a nation, bolstering national identity myths in the process. “The right identity myth, well performed,” Douglas Holt writes, “provides the audience with little epiphanies – moments of recognition that put images, sounds, and feelings on barely perceptive desires.” This has the effect of easing social tension because it helps shape and nurture a sense of identity and purpose that provides stability in periods of social or cultural stress. Berton did precisely this with The Comfortable Pew and The Smug Minority, for these polemical works told Canadians that the churches, the business class, and the politicians were out of touch with a Canadian ethos that was compassionate, equitable, nurturing, and caring, and that ordinary Canadians could rectify the problem. This is what many Canadians wanted to believe about themselves, and Berton helped validate the desire. In this process, his brand became more than simply a well-known entity. It had taken an important step toward becoming iconic.

V

Publication of The National Dream and The Last Spike in 1970 and 1971, respectively, witnessed the consolidation rather than the creation of the Berton cultural brand. After leaving the Star in 1962 because its daily grind made writing books impossible, he re-joined Maclean’s in 1963 with the offer of his own page, only to find himself fired the next year. The nominal reason was the uproar created when he appeared to advocate pre-marital sex in an article called “It’s Time We Stopped Hoaxing the Kids about Sex”; but more likely, in my view, he was fired for writing two hard-hitting articles attacking opponents of medicare, who were rattled by its coming to Saskatchewan two years earlier and fearful of a national version.

By this time Berton’s presence was ubiquitous on Canadian airwaves. He was seen weekly on “Front Page Challenge.” He could be heard eleven times a day in five-minute slots on private radio, talking about issues of the day. Long a regular interviewer on CBC television’s interview show “Close-Up,” by 1962 he had his own daily television interview show, shot on location in Toronto, Los Angeles, New York, and London.

As with his column for the Star, on his interview show one could never predict his subject. One night it might be an interview with June Callwood, the next with cartoonist Al Capp. Jack Ruby’s lawyer might be trailed by sexologist, Joyce Brothers; one night a convict, the next a nun or a prostitute. Sometimes he interviewed interviewers, such as Mike Wallace and David Frost. Satirist Lenny Bruce appeared not long before he died of a drug overdose. Political activist Malcolm X expressed reservations about the Black Panthers on Berton’s show about the Black Muslims in January 1965; within a month he was assassinated – by a Black Muslim. Each night’s show, whether with the stripper Gypsy Rose Lee or the philosopher Bertrand Russell, the journalist Norman Depoe or the singer Neil Young, advanced Berton’s status as a leading international celebrity.

The show continued until Berton called it quits in 1973 to concentrate on books and a return to history. Yet some interviews from “The Pierre Berton Show” live on – revealing ones, for example, with actor Bruce Lee and Black Power activist Malcolm X. So does a fascinating “Close-Up” session with the American literary critic Lionel Trilling and the Russian-American novelist Vladimir Nabokov not long after the publication of Lolita – thanks to clips on YouTube.

Begun in the midst of this frenzy of activity in other media and under the inspiration of Expo 67, Berton’s true “breakout” book, The National Dream (1970), appeared in the heyday of the “new nationalism” of late sixties and early seventies Canada. Together with The Last Spike, which followed the next year, Berton’s arduous saga, marketed collectively as The Great Railway, once again put him at one with the Canadian zeitgeist. The overarching theme of a transcendent nationalism made possible by a railway line had gained ascent slowly in his mind, but was in place by early 1968 when Berton complained to Canadian Pacific’s Chairman and CEO, N.R. (“Buck”) Crump, after being refused access to the CPR’s key financial records. “We would have no country without it. … There is no way to untie Canadian history from company history. The two are identical.”

Berton’s romantic nationalism was an extension of the “Laurentian Thesis” developed earlier by Canadian historians Harold Innis, J.M.S. Careless, and Donald Creighton, especially in Creighton’s two-volume biography of Sir John A. Macdonald; for there, the building of the CPR stood as the virtual embodiment of Macdonald’s national vision. But this was not the only impulse at work in shaping Berton’s story of Canadian history in the 1870s and 1880s. He could not escape the influence of the contemporary scene.

By the end of the 1960s, expressions of nationalism in Canada, so innocent and inspiring when historian Frank Underhill said in 1964 that “a nation is a body of people who have done great things together and who hope to do great things together in the future,” and so unabashedly evident during the centennial, had begun to wane among supporters. Most Quebec nationalists wanted a better deal for their province, and some argued for Quebec’s outright independence. But at least this view sprang from hope. Nationalism in the rest of Canada had come to be rooted in fear - fear of the separation of Quebec, fear of American economic and cultural domination, fear of the “Americanization” of Canadian higher education, fear of American imperial and military aggression. English-Canadian nationalists found it difficult to express themselves in ways that were unambiguously positive.

The True North Strong and Free: Part 2 – Close the 49th Parallel (1968). Polyurethane and ink on wood. 60 x 63.5 cm. ©The Estate of Greg Curnoe. Collection of Museum London, Art Fund, 1970

The years when Berton researched and wrote The National Dream and The Last Spike were paradoxical, for the rise of nationalism in English-speaking Canada occurred in an atmosphere of national dread. From the mid-1960s to 1970, the year when The National Dream was published, a spate of books and anthologies with alarmist titles and dire themes appeared, such as Lament for a Nation; the Defeat of Canadian Nationalism (1965), The New Romans; Candid Canadian Opinions of the U.S. (1968), and The Struggle for Canadian Universities (1969). Each in its own way addressed the crisis in Canadian nationhood and the problem of maintaining the country’s sovereignty and culture. When Berton’s first railway volume appeared on bookstore shelves, Ian Lumsden’s edited collection Close the 49th Parallel; the Americanization of Canada (1970) and Kari Levitt’s book Silent Surrender; the Multinational Corporation in Canada (1970) were already there. Two years later, Margaret Atwood would give her study of Canadian literary identity a stark one-word title: Survival.

Lament, struggle, surrender, survival. In the months when Berton assembled the Canadian nation in his mind and put the story of one of its greatest ventures to paper, he was aware of the culture of fear in the Canada of his own day, and set out to do something about the problems that fuelled it. Berton later noted in his memoirs that in 1969 he had lunch at Toronto’s King Edward Hotel with Peter C. Newman, then the editor of the Toronto Star, and gave his full support to Newman’s proposal for a new organization that would rally citizens to the nationalist cause. The initiative was to be backed financially by former Liberal cabinet minister and economic nationalist Walter Gordon, closely connected to the left-leaning Toronto Star. The next year, Berton became an active and vocal founding member of the Committee for an Independent Canada.

VI

Book reviewers, columnists, and of course Jack McClelland and McClelland and Stewart, served the purpose of expanding and consolidating Pierre Berton’s brand. The critics increasingly associated his persona with Canada’s aspirations and values, past and present, as they had been doing even before The National Dream appeared. But now such nostrums had been given body and life. “Pierre Berton’s National Dream,” ran the headline above a profile written by Toronto Star books columnist Peter Sypnowich.

Berton told Canadians how a newly founded Canadian nation had built not just a transcontinental railway but “a workable alternative to the United States.” Surely, went the implication, the larger, stronger, and wealthier Canada of the 1970s could resist the United States once more. Berton’s railway saga was not only about trains and spikes; it was also about the courage and resolve of a people. The National Dream called for national resolve in uncertain times, and the basic message of The Last Spike was that such resolve could result in great national accomplishment. And if this proved so in the 1870s and 1880s, years of great depression, it could happen again a century later.

The influence of the characteristics with which these ‘actors’ imbued Berton, along with the cultural meaning they ascribed to his books, was essential to the creation of his brand. The National Dream resonated with Canadians far beyond its explication of their history, significant as that was. In a time of confusion, uncertainty, and fear for the future, Berton gave them hope. Canadians had tackled impossible tasks before, and had prevailed. In the nineteenth century they had repelled American influence, and built a railway with little American or British financial support. They had done so when the political system was in as much turmoil, and was even more corrupt than it seemed to have become a century later. The title of Arnold Edinborough’s Financial Post article captured the possibility of building a nation regardless of circumstance: “Dream, nightmare or insanity? All three – but it built a nation.” It had been done before; it could be done again. All that was needed was national will.

The reception accorded to The National Dream by Canadian opinion-makers, ‘authors’ of his brand, realigned and further entrenched the image Canadians held of Pierre Berton. His association with progressive social causes remained, as when a Queen’s University student newspaper early in 1971 called him “the conscience of the nation” for having championed youth, condemned the Vietnam War, opposed Trudeau’s imposition of the War Measures Act, encouraged a greater understanding of Quebec, and supported government legislation to limit American foreign investment in Canada.

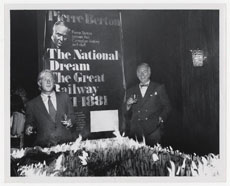

Jack McClelland and Pierre Berton celebrate the launch of The National Dream, 1970. William Ready Division, McMaster University Library

In becoming Canada’s new-found Homer, spinner and interpreter of foundational myth, Pierre Berton had acquired the stature of pater familias, along with its aura. The unnamed author of one extended review of The National Dream made the connection between the message and the man: “The National Dream reminds us that Pierre Berton also happens to be one of the most brilliant journalists Canada has produced, and that his entire career has been dominated by a profound love for this country and its people.” In a Telegram review, John Bassett wrote that he did not make “the mistake of some historical writers by treating the narrative as if it happened a long, long time ago and had no relevance today.” Read it carefully, Bassett said, and you will see not only the roots of contemporary western alienation but also that for John A. Macdonald “the price was worth the prize.” The title of the Toronto Star review was, “Pierre Berton creates a new Canadian mythology.”

The critics had begun to associate Berton himself with Canada’s aspirations, past and present, even before The National Dream was published. Journalists were essential to the creation of Berton’s cultural brand, since they were the opinion makers, the people who told the brand’s own story, thereby affording it meaning. Just as a half-decade earlier they had written about Berton as the ordinary Canadian’s champion and protector, perhaps the country’s leading crusader against inequality and discrimination, so now they added to their stock of distinguishing attributes his role as cataloguer, interpreter, and guardian of the nation’s past, and they gave resonance and luster to his persona. In the Vancouver Sun, John Rodgers wrote that the old Canadian Pacific locomotive at Kitsilano Beach was a reminder of an older Canada, a nation with “a great dream” that did not “vanish into airy nothings.” Berton told Canadians how a newly founded Canadian nation had built not just a transcontinental railway but “a workable alternative to the United States.” Surely, went the implication, the larger, stronger, and wealthier Canada of the 1970s could resist the United States once more. Berton’s railway saga was not only about trains and spikes; it was also about the courage and resolve of a people.

Academic and journalist alike picked up on the psychological significance of Berton’s railway books for contemporary Canadians. In 1973, when the full effect of The Great Railway could be assessed, Queen’s University historian Donald Swainson concluded that “the enormous success of these books illustrates the deep desire possessed by middle-class English Canadians for national symbols and identity.” The title of a report in The Wall Street Journal the same year spoke to its impact: “Canada’s Pierre Berton Succeeds By Reinforcing a National Identity.” The country’s “most popular historian, its all-time best-selling author and … superstar of Canada’s electronic media,” the Journal stated, had all but become its resident therapist, “helping to solve a kind of national identity crisis.”

Pierre Berton served up The Last Spike as he did the cocktail named after it – to reduce inhibition and galvanize resolve. The story begun in The National Dream now came to its resolution, and the story it told of great national accomplishment over adversity gave English-Canadians not simply a sense of the past, but a vicarious sense of personal satisfaction. In the transition from national dream to last spike, Berton’s dialogue with Canadian readers shifted from alleviating their fear to fuelling their desire. Fear and desire: the very core of the ad-man’s world, and the psychiatrist’s. This was the final stage of the imprinting of his brand. Everything more would be a matter of expansion and consolidation. To destroy the brand, now mature, would require Canadians to repudiate not just Berton, but themselves.

VII

Each of Berton’s major books after this served a similar cultural purpose. Hollywood’s Canada (1975) warned against the manipulation of Canadians’ image of themselves by the USA, and suggested the need for a clear sense of ourselves, articulated by ourselves. This clarion call came at a time when the glow of the New Nationalism was beginning to fade. Tensions increased within Canadian society after the OPEC oil crisis of 1973, pitting West against East in Canada. The beginnings could be seen of an aggressive lobby by international financiers, banks, and industrialists for privatization and globalization. Capital knew not the loyalty associated with borders. Thatcher and Reagan were on the horizon.Berton’s history of the War of 1812, The Invasion of Canada (1980) and Flames Across the Border (1981), arrived in bookstores in the first flush of Thatcherism and Reaganomics. Most reviewers rewarded The Invasion of Canada, the story of the origins and first stages of the War of 1812, with plaudits. The warm reception confirmed and entrenched the status Berton had won as Canada’s favourite and best popular historian with his railway books. Critics praised the liveliness of his prose, the immediacy of his story, and the value of his effort to make Canadians better acquainted with their own past. For readers in a nation others thought to be dull, and whose citizens tended to believe the canard, Berton offered up a history stitched together with larger-than-life personalities – Sir Isaac Brock, the brave English martyr of Queenston Heights; Tecumseh, Chief of the Shawnee, proud and loyal to the British cause; William Henry Harrison, the ambitious and ruthless Governor of Indiana Territory, later an American president – figures from a war of which Canadians were generally ignorant.

In a review of The Invasion of Canada, the eminent Canadian literary critic George Woodcock wrote that Berton had shown himself to be “the most truly populist of Canadian historians in the sense of being aware constantly of the ordinary people whose view of the events they move through is often more earthily accurate than that of the ‘great men’.” The very way Canada’s most popular historian exposed myths and humanized heroes – showing, for example, how the idea of military gallantry led Brock to his death – helped valorize the lives and significance of ordinary Canadians. Berton’s overall intent was to demonstrate that this war, however foolish, had instilled in Canadians for the first time a fundamental difference in political and social values from the United States, and that a reawakened awareness of this foundational moment in Canadian history could serve once again to keep the barbarians from the gates.

From this war, however ridiculous, had emerged a genuine sense of shared values that allowed British North Americans still loyal to the Crown to differentiate themselves from the American polity to the south. With it came the individuated frame of mind necessary for independent nationhood. Thousands of Canadians bought The Invasion of Canada and Flames Across the Border, its successor, and took away from the two books precisely this message. The books provided a means of fortifying their national commitment (at least vicariously) at a time of renewed assault from without and within during the years of Reagan and Thatcher. Why We Act Like Canadians (1982) became Berton’s antidote to Reaganism and Thatcherism. Those who had embraced the nationalism of the seventies found in this polemical little book a handy primer to help confirm and explain to themselves why they thought as they did and how their values fed into a sense of collective identity.

VIII

And so it continued, for the remainder of Berton’s Century. The Promised Land; Settling the West, 1896-1914 (1984) addressed growing regional discontent and distrust between provinces and federal governments. Ramsay Cook, like other reviewers, recognized the book’s contemporary resonance. A long-standing critic of effusive nationalist sentiment, he wrote: “... the old master popularizer has done it again. He has fallen upon a good story and dressed it up as only an old Star man could. He knew when it was time to celebrate the national dream. He recognized the cultural nationalistic market when he wrote Hollywood’s Canada. This book makes its appearance as a new version of western regionalism is passing from outraged infancy to the age at which it will want to read about itself.”

Vimy (1986), which appeared on the eve of the sixtieth anniversary of Canada’s greatest military battle of the First World War, laid out the heroism and horror of the taking of Vimy Ridge and explained why Canadians in 1917 saw the battle as an important milestone in the making of the nation, and provided an abundance of evidence why Canadians who read the book should remain proud of their forebears. But for Canadians in the 1980s, with memories fresh of the dozen-year American adventure in Vietnam, the book also reflected the anti-war views of the decade. “Was it worth it?” Berton asked; “… The answer, of course, is no.” Once again, a Berton book took an important event in Canadian history, evoked its mythic dimensions, and then punctured and reconstituted the myth in such a way that it continued to hold enduring power. The war had not been worth the sacrifice, but Canada had indeed come of age. Vimy was very much, in Berton’s view, “a new book for a new generation.” When he wrote it, he had in mind a remark made in one of the reviews of The Last Spike – to the effect that “every generation gets, and in fact needs, its own version of the building of the CPR.”

Two years later, in The Arctic Grail: The Quest for the North West Passage and the North Pole, 1818-1909 (1988), his epic volume on Arctic exploration, Berton recapitulated the quest theme in Canadian mythology, consistently present in his books since Klondike. Written when Canadian Arctic sovereignty was under threat by Americans, the story of the imperial struggle to be first through the Northwest Passage and the subsequent rush to reach the North Pole once again had a very obvious contemporary message. The issue of arctic sovereignty, renewed with the controversial 1985 voyage of the U.S. Coast Guard icebreaker Polar Sea through the North West Passage without Canadian government permission, and kept in the public mind by the 1987 decision of the government of Brian Mulroney to build and station a fleet of nuclear submarines in the high arctic, was very much on Canadians’ minds in the fall of 1988. The country was in the midst of a federal election campaign, set for November 2. In a televised debate, Liberal leader John Turner accused Prime Minister Mulroney of abandoning the east-west political axis created by Macdonald and maintained by Laurier and his successors for a north-south trading zone that would reach from Mexico to the high Arctic. Liberal television advertisements showed an American trade negotiator telling his Canadian equivalent that only one thing was needed in the new free trade agreement: elimination of the Canadian-American border.

The Arctic Grail made its appearance in the midst of this volatile environment, and the contemporary political message of its tales of high adventure was clear. The book was filled with foreign nationals who had laid claim to Canada’s land and waters. Berton spent the first half of The Arctic Grail focused on nineteenth century British explorers who represented imperial interests, like Sir John Franklin – heroic but foolish in his haughty refusal to adapt to arctic conditions or ways, even for survival. In the second half, he dwelt on the exploits of Robert Peary and Frederick Cook, Americans out to be the first to reach the North Pole – brash, self-promoting, egomaniacal men. And con artists. Berton’s Peary was a liar, and his Cook an outright fraud. In fact, the whole search for the new Holy Grail, whether in the form of the Passage or the Pole, was in Pierre’s view little more than a glorious con game. “What matter if the Passage was commercially impractical?” he asked. “England was about to embark on a new age of discovery in which it was the exploit itself that counted.” The Americans “had one thing in common – a desire to win at any cost, unfair or foul. In this obsession they were harbingers of the new century – the American century – in which winning is everything and it matters not how you play the game.”

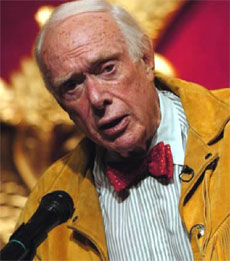

Pierre Berton reciting Robert Service’s “The Shooting of Dan McGrew” at Berton House Fundraiser, Toronto, September 2004. Pierre Berton Estate

Canadians, in short, needed to shed vestigial European and American values and cultivate and treasure those adaptable to Canada’s cultural and political as well as natural environment. If Canadians did not take preventive action, Berton warned, they, too, would find themselves victims of the politician as confidence man, ambitious and venal enough to gamble with the country’s future. Canada could be lost. Reviewers took up the alarm. “As our nation moves through the second quarter of its second century, we have begun to realize how much of our past and our future lies in that vast region, and that if we don’t claim it, other nations will,” wrote one, from resource-rich Alberta. “If we have an identity at all, it lies in the true north.” Berton’s “knack for events and personalities that reveal how Canadians came to be Canadians,” he added, “has made him an oracle of the Canadian psyche.” After a year in which he published only a volume of memoirs, Starting Out (1987), the oracle was “back in the history game.”

The high water mark of the Berton cultural brand had been reached, now fully and irrevocably iconic.

NOTE:

An earlier version of this article was given as the Special Plenary Lecture to the Canadian Association for the Study of Book Culture, Congress of the Social Sciences and Humanities, Carleton University, Ottawa, 27 May, 2009. I am grateful to Leslie Howsam and her advisors for the gift of this occasion. The piece is drawn from Pierre Berton: A Biography (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 2008).