Alexander Young Jackson. “Mountain Ash, Grace Lake” (1940), Oil on canvas. Collection of Carleton University Art Gallery: The Jack and Frances Barwick Collection, 1985. Reproduced Courtesy of the Estate of the late Dr. Naomi Jackson Groves.

IN A 1936 ARTICLE in Saturday Night Magazine entitled “False hair on the Chest,” university professor and social critic Frank Underhill provocatively declared that ”All the world knows that, apart from such efforts as growing unnecessary wheat and building railways for which there is no traffic, we Canadians have not distinguished ourselves in imaginative ways.” He cited the lack of an atmosphere of vigorous and realistic criticism and accused Canadian artists and critics of being overly enamoured with the artistic cult of the Pre–Cambrian shield – that is, landscape painting and sculpture of Ontario’s northern region. Focusing explicitly on the Group of Seven, Underhill suggested that critics (and perhaps naive Canadian viewers, more generally) had misinterpreted or missed entirely the social implications of the Group’s work, casting them romantically as “Men of the North and nothing more.”

For Underhill, these spectators had failed to grasp Canada’s north as an interpretive ‘tool’ – as a geographical venue through which to make sense of one aspect of Canadian life. The maudlin infatuation with images of desolate northern country had become merely and tragically a means to “escape from Canadian life.” Perhaps more crucially, younger artistic imitators had “simply adopted” this “vital energy” as the popular pose of the day. “It is high time to call a halt to all this posing among our contemporary artists,” Underhill noted defiantly; “…it is time that we demand from our artists that they cease to be mere escapists and that they concentrate their gaze upon the life that is actually lived by our ten million Canadians and tell us what they see there. For where there is no vision among its artists a people perisheth.”

For Underhill, the Group of Seven artists did not paint the north as such; they painted, rather, the absence of the “the civilization of Toronto” – where they all lived and gathered inspiration in collective contemplation at such venues as the Toronto Arts and Letters Club. “Those bleak barren shores, those tortured rocks, those twisted frustrated tree–trunks, represented ‘the waste–land’ of Toronto.” This, Underhill argued, was what had made the Group’s work significant to an emergent form of cultural maturity – their “passionate reaction against all the values of our civilization...trying to tell us what they saw in Canadian life and how they felt about it.”

Underhill, who spent most of his adult life in Toronto as a professor of history at the University of Toronto, generally despised the city and its people, characterizing them as “...the most self–centred complacent lot of conventionalists on the face of the earth.” Upon his arrival in Toronto in 1927 to assume a position at the university, Underhill found a city “cursed [by a] North American individualist civilization,” run by business interests and the wealthy,” and devoid of the kind of expansive intellectual atmosphere Underhill expected of an urbane and cosmopolitan city.

Underhill’s scathing comments in the pages of Saturday Night on the conditions of art and artists’ relationship to society were not simply abstract musings. They were expressions of an anger provoked by Bertram Brooker’s 1936 issue of the Yearbook of Arts in Canada, which Underhill had agreed to review for The Canadian Forum. The review appeared in the December 1936 issue of The Canadian Forum. The by–line at the top of the review, “The Canadian as Artist,” signalled and set the stage for Underhill’s virulent criticisms in the review. In his customary caustic style, in the first paragraph he insulted the author, the Association of the Canadian Bookmen and their “so–called book–fair,” and the Royal Canadian Academy of Art’s annual exhibition, on display at the Toronto Art Gallery (now the Art Gallery of Ontario). “Experiences such as these,” he noted, “leave one in a jaundiced mood for the contemplation of Canadian art in general.” Ever the intellectual provocateur, Underhill often found himself engaged in debate over the books he read and reviewed for the Forum.

As preparation for reviewing the long–delayed 1936 edition of the Yearbook, Underhill revisited the 1928/1929 issue (the last issue produced in the series) as a means of gaugeing the temper of contemporary art and criticism some seven years earlier. Re–evaluating the contributions in the 1928/1929 Yearbook, Underhill perceived a fervent “manifesto” on the arts, linked to the work of the Group of Seven, which suggested that “we Canadians … we Men of the North with our Pre–Cambrian Shield, are going to show the world.” Even contradictory and pessimistic assessments on the arts by dramatist Merrill Dennison and architect Eric Arthur, Underhill noted, were deeply shaped by the “intoxicating year of 1929. It was the boom and they were merely giving expression to what more vulgar fellow–Canadians were expressing in skyscrapers and railway extensions.” Underhill noted that “the excitement of these artists was palpable on every page.”

Turning to the 1936 Yearbook, Underhill was provoked to ask what “effect seven years of a world depression have had upon the tone and outlook of Canadian artists.” He noted:

…the depression has made us conscious that we face not merely an economic but a spiritual crisis in our civilization. In Europe that long era of individualism and liberalism which began with the Renaissance is closing in on revolution, and men are having to decide whether they will go fascist or communist. European artists have been compelled to rethink the whole question of the relation of the artist to society, and the finer spirits among them, as far as I can make out, are deciding one after another that in our troubled times the artist must be red or dead.

Seemingly exasperated, Underhill enquired rhetorically, “What has been the impact of these world–shaking events on Canadian artists?" He concluded that Canadian artists had clearly not been moved by the unfolding events in Europe, which he characterized as a “civilization dissolving before their eyes.” He levelled a direct attack on Brooker, who seemed to Underhill to advise artists to avoid the temptation of becoming involved in the political fray and the controversies of their day in favour of divine contemplation and individual creation. “I find him more comprehensible when he expresses his mysticism in lines and paint than when he tries to do it in words,” he suggested, questioning Brooker’s ability to articulate his ideas clearly.

Brooker’s definition of the artist as “a person whose experiences crystallize into unified wholes that can be embodied in some medium, as contrasted with persons whose experiences seem fragmentary, unrelated, and chaotic,” provoked Underhill’s socialist beliefs. In critiquing Brooker’s literary abilities, and in utilizing the term “mysticism” in opposition to Brooker’s term “spiritualism,” Underhill intended to sever the latter from any kind of Judaeo–Christian context and to denote it as an esoteric and gossamer web of reasoning, open to critical (academic) analysis and ultimately dismissal. The provincialism and apathy of Canadian artists, the “escapist” art they produced, and their lack of involvement and comment, artistically and otherwise, on the political and societal conditions of their time, inflamed Underhill’s socialist passions and political beliefs. No stranger to controversy, Underhill knew that his provocation would incite artists to respond and engage in a dialogic debate about the function of art and artists in society.

II

Elizabeth Wyn Wood. “Passing Rain” (1928, carved 1929), marble, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Reproduced Courtesy of the Estate of Elizabeth Wyn Wood and Emanuel Hahn, sculptors.

With the gauntlet thrown, Canadian artists were quick to respond to Underhill’s seeming incursions into their field of practice, and their own values, attitudes, and beliefs about the arts. Sculptor Elizabeth Wyn Wood, herself a regular contributor to the Forum, assailed Underhill for the way in which he erroneously applied political theory to the function of the arts in society. A well–respected artist who was intimately connected to Toronto’s artistic elite, particularly members of the Group of the Seven, Wyn Wood’s retort to Underhill was clearly undertaken as she recognized herself as one of those alleged “younger artistic imitators [who] had 'simply adopted' this 'vital energy' as the popular pose of the day.” Critically, Underhill never critiqued or disparaged the Group of Seven members, many of whom he knew personally; he directed his indignation at their self–fashioned inheritors – in this case, Wyn Wood’s generation of artists.

Wyn Wood deemed Underhill’s comments to be not only an attack on the freedom of artistic practice and expression but specifically on a younger group of artists, who the outspoken professor in essence pronounced as isolationists, derivate, and devoid of original ideas. The artist countered with a February 1937 article in the Forum, “Art and the Canadian Shield,” in which she dismissed Underhill as “riding a presently fashionable wave, wherein the idea of art as propaganda, serving the party, diarizing current experience, is easy to comprehend and insist upon. It is a mild epidemic of the Early Christian Martyr – Communist – Oxford Group fever which demands the consecration of all talent to the services of a readily recognizable cause.” Those artists, Wyn Wood pointed out, “had some doubt about the importance of civilization.” In walking off to the “hinterland,” the Canadian artist was, according to her, seeking “reality” and expressing his/her displeasure with society, arguing that the “gadgets and the civilization ... somehow [are] not the be–all either of life or culture.” She outlined a dichotomised separation between the city (civilization) and the wilderness (the divine), heralding the wilderness as the space that sustains the artist through spiritual stimulation and nourishment. “Therefore, it should not surprise [Underhill] ... that the artist should remain unimpressed by the dissolution.”

Citing a litany of Canadian artists, from Krieghoff to Yvonne McKague, who had “misgivings of about the coming” civilization or who chose to find artistic and spiritual refuge in the wilderness, Wyn Wood noted: “Myself, I have lain on the rock between the sky and water and I have remembered that thousands of men, in different parts of the world, throughout all the ages, have lived in peace, in happiness and in creative energy without knowing the organization we call civilization.” “What should we do instead?” she asked rhetorically. “Paint the Russian proletariat standing on the fallen Cossack ... or ... paint guns standing in rows, waiting ... or castles tumbling in Spain?” “Wars, depressions, peace and social security influence the arts, but art does not necessarily document these events,” she noted defiantly.

In a critical attack on Underhill himself and his supposed soap box from the groves of academe, Wyn Wood asked: “Should we then turn to our own oppressors – make cynical statues of the academic capitalist with his paunch and silk hat”? Referring to “paunch” and “silk hat,” she mockingly attempted to call into question Underhill’s own elite class status and his alleged support of the Depression’s destitute and downtrodden. In contrast to continental Europe, the American continent, she reasoned, was "marked by a measure of classlessness and of racial co–operation.” She added that “Public education, government services, mass production and certain degree of equality of opportunity had provided a background which has been conducive, though still incompletely, to the interlocking of class attributes and the merging of racial differences.” Perhaps, she mused, this might be the ground for Canadian art to “function socially ... as art for all, [her emphasis] for the first time in history of the world, not for the propagation of an ideology but itself a treasure, and enrichment of life.” Wyn Wood countered that a regimented class structure and the subservience of all creative practice to political and economic ideologies was a European passion, not an American one. Recalling a recent exhibition of art from the Soviet Union, she recalled that, “while technically exciting,” it was nothing more than “essentially false, derivative and of little stature.”

Wyn Wood was convinced that Canadian artists must respond contextually to the conditions of their own time and geographies. “If a great art is to grow up in Canada,” she noted, “it is likely to come from our natural lives as from hysteria.” She pointed out that Canadian artists weren’t necessarily “unaware” of the world around them and the conditions that often beset it, but chose to reside in the “deep passion for the slow and solid life this continent gives.” She reminded Underhill that “Canadian artists are mostly sons of pioneers who left the old lands with their unhappy civilizations, outworn customs, hatreds, oppressions, and prestige manias to come to a wilderness, free and hopeful, and who have found peace and some measure of fulfilment along with the half–civilization they have made.” Finally, she noted:

I proclaim the long stride, the far vision, the free spirit...let us have criticism that is sound and technical, let us have sincere, understanding receptivity. Let us not fear simplicity. Some day we may have to take in the refugees from a smouldering civilization. We may have to offer them more than bread. We may have to offer them the spiritual sustenance of an art which grows on the bare rock and bare chests.

Wyn Wood was adamant that art would survive and flourish under any conditions.

Wyn Wood’s poetic admission would prove a source of outrage for the Soviet born artist Paraskeva Clarke (1898–1986), who published a spirited rejoinder, “Come Out From Behind the Canadian Shield,” in the New Frontier (April 1937), a fledgling magazine that had situated itself to the left of its model, the Forum, and which addressed itself to much the same audience. Clarke agreed with Underhill’s sentiments that adhering to a back–to–the–wilderness mantra and claiming it as a form of “spiritual refuge” from civilization was nothing more than a denunciation of one’s obligation to active citizenship. Although Clarke was agnostic on Underhill’s “sensitivity” and “competence” to raise artistic issues to a broader lay public, she welcomed his remarks for representing “a strident and almost reflex outcry against the complacency and self–satisfied remoteness of the Art and Artists of the Pre–Cambrian Shield.’”

In her response to Wyn Wood, Clarke and her scribe G. Campbell McInnes boldly confronted Wyn Wood’s assertions. Clarke was incensed with Wyn Wood’s dismissal of Underhill’s pronouncement that artists in Europe were being forced to go “red or dead,” and particularly with how Wyn Wood viewed such positioning as denigrating “the divine nature of the artistic personality.” “Red art,” Clarke angrily replied, “has for Miss Wood only the conventionally standardized meaning.” Such feeble interpretations,” she said, were “the tell–tale sign of careless thinking,” demonstrating how the “exaltation of the individual can blind an artist to the forces which approach to destroy that relative security in which he is permitted to exercise his individuality.” More emphatic and biting even than Underhill, Clarke proclaimed that “Miss Wood’s aloofness, and that of others like her, from the life of their country, make them all oblivious to what is going on around them.“ For Clarke, Wyn Wood’s “glib” and pithy statements on the arts’ and artists’ role in the social struggle not only betrayed a lack of insight but was symptomatic of the larger social constructs such as capitalism, with its focus on individualism, profit, and instrumentalist logic.

Concerned that Canadian artists were oblivious (consciously or unconsciously) to peoples’ everyday struggles, and seeking to unearth the conception at the heart of Wyn Wood’s beliefs, Clarke asked rhetorically, “Who is the artist?” Is the artist a breed apart from ordinary people, or someone “human” just like them, endowed with the singular ability “to arouse emotions through the creation of form and images?” Clarke insisted that those involved in the “social struggle” had the right to expect the sympathetic support of the artist, who would serve in an “inspiring role” for the ultimate “defence and advancement of civilization.” It saddened her, inevitably, “that such an appeal is treated only as a ‘presently fashionable wave.’” In order to make Wyn Wood’s notion of the artist evident to all, Clarke highlighted what she believed was a link between the “consecration of [artistic] talent” and the idea of “royalty.” She added that while twenty years ago the “artist of the pre–Cambrian Shield might have been performing a important function in stirring people to a “sense of their country’s beauty,” that project was completed. It was “time,” she told Wyn Wood, “to come down from your ivory tower.” Exasperated that Wyn Wood and other artists were ostensibly unmindful of the social anguish and distress in their own communities, Clarke could not contain her anger:

Forget, if you wish, the troubles of Europe, there are plenty here. Paint the raw, sappy life that moves ceaselessly about you, paint portraits of your own Canadian leaders, and depict happy dreams for your Canadian souls. But if you cannot do all this, for it is a new and difficult problem, at least have the grace to refrain form being scornful of those who do, those who are saying necessary things and proving of immense value to their time. Think of yourself as a human being, and you cannot help feeling the reality of life around you, and becoming impregnated with it.

Emphasizing the complexity of class relations and Wyn Wood’s own class privilege, Clarke noted that for one to “lie on a rock between and sky and water ... other thousands suffered that they might do so.” She added, “It is to enable you to lie on a rock that castles are tumbling in Spain.”

For Clarke, esoteric, abstract art, swathed in “sophisticated artistic intellect,” and “divine irreality,” discussed only by a small group of intellectual elite was about as useful as a “top hat to a Tatterdemalion beggar in the midst of winter.” Likewise, to yearn for past art glories, as Wyn Wood did in her nostalgic recall of ancient Egyptian and Greek monumental art, was to overlook the inequitable class relations that existed in the past and how they have continued, in part, to inform the present. Clarke noted that Wyn Wood’s romantic pining was tantamount to “an implied longing for the good old days of slavery.” Recalling Wyn Wood’s comment that art would survive and flourish under any conditions, Clarke admonished her for failing to consider the human being behind the art.

Take actual part in your own times, find their expression and translate it to help your fellow man in the struggle for the future and dream of art which this future will produce. Why should we take it for granted that the artist should be left in the garret to paint his apples? He does so today because he is not now, as he will be in the future and as he was in the past, an integral part of a well–ordered society, performing a necessary function.

“Why,” Clarke noted, “do the people and their struggles and their dreams not interest you?" Clearly frustrated, she noted defiantly that when the new social order arrived, artists of the Pre–Cambrian shield, like Wyn Wood, despite their interest in being involved in the process of reconstruction, “would not understand the language of this new order.”

In the 1982 video, The Portrait of the Artist: as an Old Lady, during an interview with Charles Hill, Clarke reminisces scornfully on the artistic themes of the 1930s. “Landscape, Landscape, landscape,” she fumes.

III

Paraskeva Clark. “Petroushka” (1937), oil on canvas, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Reproduced Courtesy of Clive and Benedict Clark.

The frequently derisive and accusatory debates in the Forum (and New Frontier) reflected the fact that questions about art's function in society, and particularly its potential to elicit and comment upon social conditions and inequities, were widespread in 1930s Canada, especially in socialist Marxist circles. Only a few years earlier, in fact, an even more vituperative debate than the one involving Underhill, Wyn Wood, and Clarke had exploded, in the pages of the left–wing periodical the Masses.

In 1931, a small group of left–leaning artists, graphic artists and writers in Toronto, provoked by the Depression and an interest in political change, formed the Progressive Arts Club (PAC). The thirty–five initial members were organized in “artists’ group, a writers’ group and a dramatic group.” Each group attempted to use its particular art form in the service of the class struggle – cartoons and poems were featured in the worker’s press and labour papers; plays were written and rehearsals commenced, and an exhibition of paintings and sculpture was undertaken. In 1932, the PAC began publishing a cultural journal called the Masses, modeled after its better–known counterpart in the United States. Among those early founders were cartoonist Toby Gordon, painter Avrom Yanovsky, and writer Dorothy Livesay. Although the Masses had a short run – only 12 issues from April 1932 to April 1934 – its impact, particularly its discussion on the function of art and artist in society, would have lasting effects in a variety of art communities throughout the 1930s. Moreover, it presaged, at least circuitously, Underhill’s concern for art and artists' involvement in social reconstruction and the creation of a new social order.

Situating themselves at the margins of the “established” art community and its trappings – the gallery, association, and awards system – and recognizing their own exclusion (“as not been crowned by the academy”), the Masses and its editors launched an all–out attack on what it deemed “Canadian bourgeois society generally, and in Canadian cultural life particularly.” Interestingly, the periodical represented itself as embodying, in its very production, a “movement” on behalf of the working, the unemployed, and the farmer. Denouncing the commonly held view that art had no relationship to politics, the Masses fervently argued that the contemporary art system and its intellectualism – “the self–styled aloofness of the ivory tower recluse” – is firmly implanted in capitalism and is itself the art of the “ruling class.” “Art ... is propaganda,” an April 1932 editorial called “Our Credentials” added, “or more precisely a vehicle for propaganda …. Art is the product of the current (and previous) social and economic conditions…. bourgeois art propagates those ideas which are most acceptable to capitalism. It is the art of a decaying society.”

Bourgeois intellectuals, the Masses argued, were also culpable for their veritable silence and disregard or disinterest in working class issues. Posing the question Underhill and Clark would ask of artists several years later, the Masses observed: “Intellectuals the world over are today reluctantly climbing down form their towers. They are taking sides. This development has not as yet very forcibly manifested itself in Canada.” They added rebelliously: “Are they eternally to remain silent”?

Silence and impartiality in the face of starvation, farm evictions, record–high employment in the cities, and deportations, marked a seemingly unfathomable sympathetic and moral gulf between working class people and middle class artists and intellectuals. Infuriated, the Masses asked rhetorically: “Are there any honest intellectuals, who will study the life of the workers, who will make the aims of the workers their aims, who will lend their art to the cause of the working class”? In response, the PAC sought through its instrument the Masses, to produce and promote an alternate group of “revolutionary” inspired artists, writers, performers, and class–conscious intellectuals – a group more attuned to the sensibilities of working class conditions, cultures, issues, hopes, and aspirations.

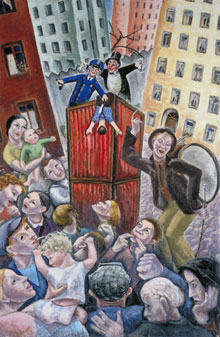

It wasn’t long, though, before artists who identified themselves as “socialist” challenged the presumption that the visual and performing arts must necessarily be subservient to the socialist cause. A contributor named T. Richardson delivered the first salvo, in an article entitled “In Defence of Pure Art.” (July–August 1932) Richardson began strategically by citing the Russian Surrealists’ declaration of an abiding allegiance to the Soviet Government but their opposition to exclusive utilization of their art in the service of the state. For “development in the arts” to take place, Richardson rationalized, “art must like science, be free to go unhampered. Restrict the artist and the artist dies; as witness the age of sterility following the dogmatic rule of the church.” According to Richardson, you could not simply dismiss art (or science) that did not directly conform to the “immediate and obvious cause of socialism.” Challenging the limits of who gets to speak on behalf of “art,” and what constituted “good” art, Richardson knowingly observed that it “is very well for the soapbox orator to grimace at all art which does not illustrate his message, but the soap–box orators do not produce art. Neither do economists nor philosophers – artists along produce art. The attitude of these people who insist upon art conveying their particular message is identical with the attitude of religionists. And we know where that leads – to sterility.”

Richardson drew a crucial distinction between art and propaganda, arguing that while “propaganda is not art; art can be propaganda.” To legitimate a work of art as “good” or “bad,” simply on the basis of its representation of a socialist ideology was to raise ”the old romantic battle cry again in a new guise,” and perhaps more generally indicated naiveté on the part of the viewer. Certainly, “a painting can represent the class struggle very well and still be very bad art. The subject matter did not govern the intrinsic value of a work of art .... [rather] Art begins where subject matter ends. Arguing that utilitarian art making and representation produced sterile and unimaginative conformity, Richardson attempted to persuade readers that it would be counter–productive to channel artistic endeavours in the service of socialism.

Immediately following Richardson’s article appeared a rebuttal, written by E. Cecil–Smith: “What is ‘Pure’ Art? Challenging Richardson’s conception of “pure” art, especially its relation to socialism, Cecil–Smith attributed Richardson’s ideas to “the position of the younger artists today.” In so doing, Cecil–Smith marginalized Richardson’s views as the blush of youthful idealism. Accordingly, Cecil–Smith attempted to deconstruct Richardson’s propositions, beginning with his assumption that “the artist alone creates art.” On the contrary, Cecil–Smith noted, “Art, literature, music can be said to have been created by society, as only the existence of society gives any excuse for its continuance. ... Without society [the function] of art ceases.” As such, Cecil–Smith pointed out that the “soap–box orator, the economist, and the philosopher,” to whom Richardson derisively alluded as interlopers in artistic practice, were indirectly essential, as members of society, in assisting the artist in “the creating of art.” Cecil–Smith noted bluntly that these alleged trespassers were “directly” involved in art making “as conscious leaders of ideology, which gives the artists ideas to paint about.”

IV

As the dispute over art and society played out, it became clear that Underhill’s intellectual assault was centred particularly on visual artists, who with few exceptions he felt were one of the few artistic groups not to comment explicitly on the “social struggle” and the Depression. Against the backdrop of a vibrant left–wing political literary and performative artistic culture, visual artists, seemingly preoccupied with concepts of “divine creation,” and ostensibly in retreat to the hinterland, could not but come under Underhill’s scathing attack. In fact, poets, and writers were intensely involved in discussions of the social problems of day, particularly questions which dealt either with the Depression, the need for social justice, or with pacifist themes of varying degrees.

The debate, and the eventual tide of post–war social reconstruction, seems to have had a lasting impact on Elizabeth Wyn Wood, for by the late 1940s she was intimately involved in re–envisioning a post–war world through the arts. For his part, “interloper” or not, Underhill played a crucial role in publicly invigorating (along with Wyn Wood and Clarke) a long–simmering debate about the function of the arts and artist in Canadian society. In the end, I think all of the participants, in their own way, would agree with Underhill’s statement that where “there is no vision among its artists a people perisheth.”

WORKS CONSULTED:

Ross D. Cameron, “Tom Thomson, Antimodernism, and the Ideal of Manhood,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, New Series 10, 1999

E. Cecil–Smith, “What is ‘Pure’ Art,” Masses, 1, 4–5 (July–August 1932)

Paraskeva Clarke, “Come Out From Behind the Pre–Cambrian Shield," New Frontier, 1, 12 (April 1937)

James Doyle, Progressive Heritage: The Evolution of a Politically Radical Literary Tradition in Canada (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2002)

R. Douglas Francis, Douglas. Frank Underhill: Intellectual Provocateur (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1986).

Michiel Horn, The League for Social Reconstruction: Intellectual Origins of the Democratic Left in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1980);

E. Lisa Panayotidis “Social Reconstruction, Visuality and the Exhibition of Democratic Ideals in Canadian Schools, 1930–1960,” In Harold Pearse, ed., From Drawing to Visual Culture: A History of Art Education in Canada (Montreal: McGill–Queen’s Press, 2006).

B. Richardson, “In Defense of Pure Art,” Masses (July–August 1932)

Frank Underhill, “False hair on the Chest,” Saturday Night Magazine (October 3, 1936)

Elizabeth Wyn Wood, “Art and the Pre–Cambrian Shield,” Canadian Forum (February 1937)

Joyce Zemans, "First Fruits: The Paintings," in Jennifer O. Sinclair, ed., Bertram Brooker and Emergent Modernism, Provincial Essays (Toronto: Phacops Pub. Society at The Coach House Press, 1989)